What is PV and where is it located?

The subclavian vein is located in front of the scalene muscle and receives the veins of the arm and neck. It serves as a continuation of the axillary vein, which receives blood from the arm belt and free upper limb.

The anatomy of the vessel is as follows: it has valves that are located from the lateral edge of the 1st rib to the sternoclavicular joint. The subclavian vein forms a venous angle due to its connection with the internal jugular vein.

The brachiocephalic veins are formed due to the confluence of the subclavian and internal jugular veins. The subclavian vein is separated from the artery of the same name by the anterior scalene muscle.

Central venous access

25.09.2011 59727

Providing central venous access.

On the one hand, the EMS doctor or paramedic is obliged to provide venous access if the patient’s condition requires it, in any situation.

On the other hand, he does not have sufficient skill in performing central venous access, which means that the likelihood of developing complications is higher for him than, say, for a hospital resuscitator who performs 5-10 “subclavicular connections” weekly. This paradox is almost impossible to completely resolve today, but it is possible and necessary to reduce the risk of complications when placing a central venous catheter by working according to generally accepted safety standards. This article is intended to remind you of these very standards and systematize the currently available information on the issue under discussion. First, we will touch upon the indications for central venous access in the aspect of the prehospital stage. I’ll note right away that they are significantly narrower than stationary readings, and this is fair. So, let's start first with the indications for central venous catheterization, accepted in a hospital setting: the need for dynamic control of central venous pressure; the need for long-term administration of introtropic and vasopressor drugs; parenteral nutrition and infusion therapy using hyperosmolar solutions; conducting transvenous pacemaker; inaccessibility of peripheral veins or discrepancy in total diameter; installed peripheral catheters and the planned rate and volume of infusion therapy. For the prehospital stage, from this entire list it is advisable to leave only the penultimate and last indications. I think this is understandable - the role of the CVP has now been significantly rethought and it is inappropriate to use it in DGE; the introduction of hyperosmolar solutions for DGE is not carried out (with the exception of 7.5% sodium chloride solution and hyper-HAES, but they can be injected into a large peripheral vein); Vasoactive and inotropic agents can also be administered peripherally for short periods of time. So, we are left with two indications for catheterization of central veins for DGE: inaccessibility of peripheral veins or discrepancy between the total diameter of installed peripheral catheters and the planned rate and volume of infusion therapy, as well as the need for transvenous cardiac pacing. The current abundance of various peripheral catheters and the use of the intraosseous route of administration can solve the problem of access to the vascular bed without involving the central veins in most cases. Contraindications for CV catheterization: infection, trauma or burn of the intended catheterization site; severe coagulopathy (visible without special examination methods); the EMS doctor’s lack of skill in CV catheterization (but in this case, the doctor faces liability for failure to provide vascular access if it is proven that this was the cause of the consequences). The question has been repeatedly raised: what should a paramedic do? Colleagues, legal practice in the CIS countries is such that no one will appreciate a central venous catheter successfully installed by a paramedic, but the paramedic can be held fully responsible for his actions if a complication suddenly occurs, especially a fatal one. Central venous catheterization is a medical procedure, but this does not mean that if a patient dies due to the lack of adequate venous access, the paramedic is insured against a showdown for “inadequate provision of medical care.” In general, fellow paramedics, in each specific situation you will have to make a decision at your own peril and risk. Intraosseous access in such situations is an excellent lifesaver. Anatomical considerations

Strictly speaking, the term “central venous catheterization” means catheterization of the superior (usually) or inferior vena cava, since the veins that are directly used to access these areas of the vascular bed (subclavian, internal jugular or femoral) are not central in in the full sense of the word. The tip of the catheter when catheterizing the central vein should be in either the superior or inferior vena cava, this must be understood.

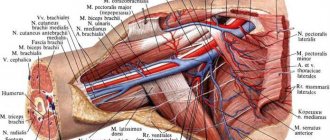

Figure 1. Anatomical relationship of the subclavian and internal jugular veins. The anatomical relationships of the structures surrounding the subclavian and internal jugular veins must be very clearly understood; for this, it is most useful to go to the morgue several times and dissect the cervical and subclavian region. In general terms, they are as follows (taken from the book by M. Rosen, J.P. Latto and W. Shang “Percutaneous Catheterization of Central Veins”): The subclavian vein is located in the lower part of the subclavian triangle. It is a continuation of the axillary vein and starts from the lower border of the 1st rib. First, the vein bends around the first rib from above, then deviates inwards, downwards and slightly anteriorly at the place of attachment to the first rib of the anterior scalene muscle and enters the chest cavity, where behind the sternoclavicular joint it connects with the internal jugular vein. From here, as a brachiocephalic vein, it turns into the mediastinum, where, connecting with the vein of the same name on the opposite side, it forms the superior vena cava. In front, along its entire length, the vein is separated from the skin by the collarbone. The subclavian vein reaches its highest point just at the level of the middle of the clavicle, where it rises to the level of the upper border of the clavicle. The lateral part of the vein is located anterior and inferior to the subclavian artery, and both of them cross the upper surface of the first rib. Medially, the vein is separated from the artery lying posterior to it by the fibers of the anterior scalene muscle. Behind the artery is the dome of the pleura. The dome of the pleura rises above the sternal end of the clavicle. The subclavian vein crosses the phrenic nerve in front, the thoracic duct passes above the apex of the lung on the left, which then enters the angle formed by the confluence of the internal jugular and subclavian veins - Pirogov's angle. The internal jugular vein starts from the jugular foramen of the skull, continues from the sigmoid sinus and runs towards the chest. The carotid artery and vagus nerve pass together in the carotid vagina. Before occupying first a lateral and then an anterolateral position relative to the internal carotid artery, the internal jugular vein is located behind the artery. The vein has the ability to expand significantly, adapting to increased blood flow, mainly due to the compliance of its lateral wall. The lower part of the vein is located behind the attachment of the sternal and clavicular heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the corresponding formations and is tightly pressed to the posterior surface of the muscle by the fascia. Behind the vein are the prevertebral plate of the cervical fascia, the prevertebral muscles and the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae, and below, at the base of the neck, are the subclavian artery and its branches, the phrenic and vagus nerves and the dome of the pleura. The thoracic duct flows into the confluence of the internal jugular and subclavian veins on the left, and the right lymphatic duct flows into the right. With the femoral vein it is somewhat simpler - in the immediate vicinity of it there are no structures whose damage poses a direct threat to life and from this point of view its catheterization is safer. The femoral vein accompanies the femoral artery at the thigh and ends at the level of the inguinal ligament, where it becomes the external iliac vein. In the femoral triangle, the femoral vein is located medial to the artery. Here it occupies an intermediate position between the femoral artery and the femoral canal. The great saphenous vein of the leg enters it from the front, just below the inguinal ligament. At the femoral triangle, several smaller superficial veins drain into the femoral vein. The lateral femoral artery is located the femoral nerve. The femoral vein is separated from the skin by the deep and superficial fascia of the thigh; in these layers there are lymph nodes, various superficial nerves, superficial branches of the femoral artery and the upper segment of the great saphenous vein of the leg before its entry into the femoral vein. The choice of vein for catheterization is determined by a number of factors: experience, anatomical features, the presence of injuries (burns) in the cervical, subclavian or femoral area. We will look at the most common time-tested accesses to the central veins. General principles of central venous catheterization for DGE Central venous catheterization is a surgical operation, therefore, if possible, conditions should be ensured as aseptically in this area. I had to place the central veins right on the highway, in a circle of onlookers, but this is not the best place for such manipulation. It is much more reasonable to carry out catheterization at home or in an ambulance (if the call is public). Make sure your team always has a central venous catheterization kit. Now there are a lot of manufacturers producing excellent sets at an affordable price. Carrying out central venous catheterization with consumables not intended for this purpose increases the risk of complications. Currently, the Seldinger technique is used for catheterization - after puncture of the vessel, a guidewire is inserted into it, the needle is removed and a catheter is inserted along the guidewire. In exceptional cases, it is possible to catheterize the internal jugular vein using the “catheter on a needle” method, and careful attention should be paid to monitoring the adequate functioning of the venous access and changing the catheter to a normal one at the first opportunity. Pay close attention to fixing the catheter. It is best to sew it to the skin with a nylon seam. General sequence of actions for central vein catheterization (general algorithm) Determine the indications for central vein catheterization. Let me remind you once again that for a number of reasons, central venous catheterization at the prehospital stage should be avoided in every possible way. But the above does not justify refusal to catheterize the central vein in cases where it is really necessary. If possible, informed consent should be obtained from the patient himself or his relatives. Select a location for access. Provide aseptic conditions, as much as space and time allow: the catheterization site is treated, hands are treated, and sterile gloves are worn. Find a point for puncture. Anesthetize the patient. Central vein catheterization is a very painful procedure, so if the patient is not in a deep coma and time allows, do not forget about local anesthesia. For puncture, a special needle and a syringe half filled with saline are used. The needle passes through the tissue slowly, trying to feel all the layers. During a puncture, it is very important to imagine where the tip of the needle is (“keep your mind on the end of the needle”). I strongly warn you against bending the puncture needle to facilitate its insertion under the collarbone - if you lose control over its position, the likelihood of complications will increase many times over. It is strictly forbidden to manipulate the tip of the needle deep into the tissue. To change the direction of the needle, be sure to pull it into the subcutaneous tissue. After receiving venous blood (the blood should flow freely into the syringe), the needle is securely fixed with fingers and the syringe is removed from it. The needle hole is closed with a finger, since it is quite possible to get an air embolism with a negative central venous pressure. A guide is inserted into the needle. Either a fishing line conductor or a string with a flexible tip is used. The conductor is inserted at 15-18 cm; with deeper insertion, the tip of the conductor can cause arrhythmias. If there is an obstacle, the conductor is removed along with the needle; It is strictly forbidden to remove the conductor from the needle in order to avoid cutting off its tip (a similar incident happened to my colleague). After inserting the guide, the needle is carefully removed. A dilator is inserted along the guidewire and, holding the guidewire with your free hand, the puncture channel is carefully expanded with the dilator, being careful not to tear the vein. The dilator is removed, a catheter is inserted along the guidewire, while holding the tip of the guidewire with your free hand (very important!). The catheter is inserted to such a depth that its tip is in the inferior vena cava when catheterizing through the subclavian or internal jugular vein (approximately at the level of the second intercostal space along the midclavicular line) and at 35-45 cm (an appropriate catheter should be used) when catheterizing the inferior vena cava through femoral The guidewire is carefully removed, an empty syringe is attached to the catheter and its location is checked. Blood should flow into the syringe freely, without resistance, and be injected back in the same way. If necessary, the catheter is tightened a little or inserted deeper. An intravenous infusion system is connected to the catheter; the solution should flow through the catheter as a stream. The catheter is fixed, preferably with a nylon suture. Apply a bandage. Now we will look at individual accesses. Catheterization of the subclavian vein Subclavian and supraclavicular approaches are used to perform puncture and catheterization. Position: the patient is placed on a hard horizontal surface, a small cushion of folded clothing is placed between the shoulder blades, the head is slightly thrown back and turned as far as possible in the direction opposite to the puncture site, the arm on the puncture side is lowered slightly and pulled down (toward the lower limb), and also rotated outward . When choosing a puncture site, the presence of damage to the chest is important: the puncture begins on the side of the damage, and only if there is massive crushing of the soft tissue in the clavicle area or when it is fractured, the puncture is performed on the opposite side. Landmarks: clavicle, jugular notch, pectoralis major muscle, sternocleidomastoid muscle. Subclavian access . The collarbone is mentally divided into 3 parts. The puncture sites are located 1-1.5 cm below the collarbone at the following points: Below the middle of the collarbone (Wilson's point). At the border of the inner and middle third of the clavicle (Obnajak point). 2 cm away from the edge of the sternum and 1 cm below the edge of the clavicle (Giles point). Puncture from all points is performed towards the same landmarks. The most common point is Obanyak. To find it, you can use the following technique: the index finger is placed in the jugular notch, the middle finger is placed at the top of the angle formed by the outer leg of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the clavicle, and the thumb slides along the lower edge of the clavicle (towards the index) until it will fall into the subclavian fossa. Thus, a triangle is formed, at the vertices of which the operator’s fingers are located. The needle insertion point is located at the site of the thumb, the needle is directed to the index finger. Technique: the skin and subcutaneous fat are punctured vertically with a needle to a depth of 0.5-1 cm, then the needle is directed at an angle of 25°-45° to the collarbone and 20°-25° to the frontal plane in the direction of one of the landmarks: 1. On the upper edge of the sternoclavicular joint from the puncture side; 2. On the jugular notch of the sternum (by placing a finger in it); 3. Lateral to the sternoclavicular joint from the side of the puncture. The needle is directed slowly and smoothly, strictly to the landmark, passes between the first rib and the collarbone, at this moment the angle of the needle in relation to the frontal plane is reduced as much as possible (the needle is kept parallel to the plane on which the patient lies). A vacuum is created in the syringe all the time (during insertion and removal of the needle) by the piston. The maximum depth of insertion of the needle is strictly individual, but should not exceed 8 cm. You should try to feel all the tissues traversed by the needle. If the maximum depth is reached and no blood appears in the syringe, then the needle is removed smoothly to the subcutaneous tissue (under the control of aspiration - since it is possible that the vein was passed through “at the entrance”) and only then directed to a new landmark. Changes in needle direction are made only in the subcutaneous tissue. Manipulating the needle deep into the tissue is strictly unacceptable! In case of failure, the needle is redirected slightly above the jugular notch, and in case of repeated failure, an injection is made 1 cm lateral to the first point and everything is repeated all over again.

Rice. 2. Puncture of the subclavian vein: a – points of needle insertion: 1 – Giles, 2 – Obanyak, 3 – Wilson; b – direction of the needle during puncture. Supraclavicular approach - considered safer, but less common. The needle insertion point (Joff's point) is located at the apex of the angle (or at a distance of up to 1 cm from it along the bisector) between the upper edge of the clavicle and the place of attachment of the lateral leg of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to it. After puncturing the skin, the needle is directed at an angle of 40°-45° in relation to the collarbone and 10°-20° in relation to the anterior surface of the lateral triangle of the neck. The direction of needle movement approximately corresponds to the bisector of the angle formed by the clavicle and the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The vein is located at a depth of 2-4 cm from the surface of the skin. I would like to note that I often use this access, but not for catheterization, but for vein puncture when immediate access to the vascular bed is necessary. The fact is that with this access the distance to the vein is very short and it can be reached even with a regular intramuscular needle. Puncture catheterization of the internal jugular vein.

Associated with a significantly lower risk of damage to the pleura and organs in the chest cavity. The authors of IJV catheterization techniques emphasized that during the development of these same techniques, not a single lethal complication was obtained. Meanwhile, technically, puncture of the IJV is much more difficult due to the pronounced mobility of the vein; an “ideally” sharp puncture needle is required. Typically, resuscitators master this access after mastering catheterization of the subclavian vein. For puncture, it is ideal to place the patient in the Trendelenburg position (lowered head end) with an inclination of 15-20°, but personally I never use this. We turn our head slightly in the direction opposite to the puncture. There are several methods (accesses) for puncture of the internal jugular vein. In relation to the main anatomical landmark, they are divided into 3 groups: 1. EXTERNAL ACCESS - outward from the sternocleidomastoid muscle; 2. INTERNAL ACCESS - medially from this muscle; 3. CENTRAL ACCESS - between the medial and lateral legs of this muscle; Among these accesses, there are upper, middle and lower accesses. With external access, the needle is inserted under the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the border between the lower and middle thirds of it (at the point where the vein crosses the lateral edge of this muscle). The needle is directed caudally and ventrally (at a slight angle to the skin) to the jugular notch of the sternum. In this case, the needle goes almost perpendicular to the course of the vein. With internal access, the second and third fingers of the left hand move the carotid artery medially from the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The skin puncture point is projected along the anterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle 5 cm above the collarbone. The needle is inserted at an angle of 30°-45° to the skin in the direction of the border between the middle and inner third of the clavicle. With central access, an anatomical landmark is found - a triangle formed by the two legs of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the clavicle. From the angle between the legs of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, a bisector is mentally lowered to the collarbone. The injection point for the upper, middle and lower access will be located, respectively, at the apex of the angle, in the middle of the bisector and at the place where it intersects with the collarbone. It is very useful to feel the pulsation of the carotid artery, it is located medial to the vein. Personally, I like the high central access the most, and I almost always use it. A needle is inserted into the puncture point and directed towards the heart area at an angle of 30°-45° to the skin and at an angle of 5°-10° from the sagittal plane (midline), that is, towards the ipsilateral nipple (anterior superior iliac spine in women ). You can first use the search puncture technique with a conventional intramuscular needle. The needle is advanced with constant aspiration using the syringe plunger. A puncture of the cervical fascia, under which there is a vein, is clearly felt; This usually occurs at a depth of 2-3 cm from the skin. If the needle is inserted 5-6 cm, but there is no vein, then the needle is carefully removed with a constant vacuum in the syringe. Quite often it is possible to “catch” the vein only when the needle is removed. If this also ends in failure, then the needle is redirected first somewhat laterally, and if there is no vein even there, more medially (carefully, since the carotid artery passes medially). After entering the vein, it is advisable to turn the needle slightly along the vein, this facilitates the introduction of the conductor. Femoral vein catheterization Requires a long catheter as it must pass into the inferior vena cava. To make it easier to remember the location of the components of the neurovascular bundle of the thigh, it is advisable to remember the word “IVAN” (intra - vein - artery - nerve). The injection point is located 1-2 cm below the Pupart ligament and 1 cm inward from the pulsation of the femoral artery. The needle is directed at an angle of 20°-30° to the surface of the skin and slightly outward. In this case, you can feel 2 failures - when the fascia is punctured and when the vein itself is punctured. Due to the displacement of the vein, it is more likely to end up in it at the exit. Complications with femoral vein catheterization are usually associated with prolonged catheterization; this catheterization is not associated with such serious complications as pneumothorax or hemothorax, which can occur with subclavian or internal jugular vein catheterization, therefore femoral vein catheterization is quite attractive for the prehospital stage. The only condition is that the patient has relatively preserved hemodynamics, since to find the puncture point, the pulse in the femoral artery must be felt. Complications of central venous catheterization 1. Associated with violation of puncture technique: Subcutaneous bleeding and hematoma, pneumothorax, hemothorax. Bleeding and hematomas due to erroneous puncture of the subclavian or carotid artery - if scarlet blood appears in the syringe, then the needle should be quickly removed, the puncture site of the artery should be pressed for 2-3 minutes and if there is a severe hematoma, repeat the puncture on the other side. Lymph outflow, formation of chylothorax when the thoracic lymphatic duct is damaged (occurs during puncture on the left). Puncture of the trachea with the formation of subcutaneous emphysema. Damage to the recurrent nerve. Damage to the stellate ganglion. Injury and paralysis of the phrenic nerve. Damage to the brachial plexus. Double puncture of the subclavian or jugular vein with damage to the pleural cavity, insertion of a catheter into the pleural cavity. Esophageal puncture with subsequent development of mediastinitis.

2. When a guidewire or catheter is inserted to an excessive depth: Perforation of the wall of the right atrium. Perforation of the wall of the right ventricle. Perforation of the wall of the superior vena cava. Perforation of the right atrium wall with catheter exiting into the right pleural cavity. Damage to the wall of the pulmonary artery during catheterization of the right subclavian vein. Penetration of the catheter into the jugular vein or subclavian vein of the opposite side. Penetration of the catheter from the right subclavian vein into the inferior vena cava and the right atrium. Penetration of the catheter into the right heart with damage to the tricuspid valve and subsequent occurrence of heart failure. If a life-threatening complication occurs, all possible measures must be taken to eliminate it. With the development of tension pneumothorax, a puncture is performed with a thick needle in the second intercostal space along the midclavicular line; you can place several 16 or 14 G catheters into the pleural cavity. You should always remember that if catheterization on one side of the chest fails, you should try to catheterize the same vein using another approach, change the vein (for example, if the subclavian puncture fails, try to puncture the jugular on the same side ). Switching to the other side should be done as a last resort, since bilateral tension pneumo- or hemothorax leaves the patient virtually no chance, especially at the pre-hospital stage. Another important detail is that if the patient has an initial pneumothorax, hemothorax, hydrothorax, pneumonia, chest trauma, pleurisy or penetrating chest injury, puncture of the subclavian or internal jugular vein should always begin on the affected side. A few words about the external jugular vein A description of the technique of catheterization of the external jugular vein is very rare even in modern Russian literature, meanwhile, this method seems quite convenient and much simpler and safer than catheterization of the central veins. Puncture of the external jugular vein works well in patients with normal or low nutrition. The patient's head is turned in the opposite direction, the head end is lowered, and the vein immediately above the collarbone is pressed with the index finger. The doctor or paramedic stands at the side of the patient’s head, treats the skin, fixes the vein with a finger, pierces the skin and the wall of the vein in the proximal direction (towards the collarbone). This vein is thin-walled, so there may be no sensation of obstruction or failure when the wall is punctured. Catheterization – using the “catheter on a needle” method.

Author Shvets A.A. (Count) https://www.feldsher.ru

Subclavian vein tributary

The venous wall is fused with the fascia of the neck, the periosteum of the 1st rib and the tendon. It is for this reason that the lumen of the vein does not collapse. This factor plays an important role, because when a vein is injured, there is a high probability of developing an air embolism.

The tributaries of the subclavian vein are:

- the dorsal scapular vein corresponds to the basin of the artery of the same name;

- sternal veins, which carry blood from the pectoral muscles.

On the right side of the neck, the Pirogov venous angle is located in front of the subclavian vein, into which the jugular vein flows.

Functions

The main function of the vein is considered to be the outflow of blood saturated with carbon dioxide and metabolic products.

In addition, thanks to it, hormones from the endocrine glands and nutrients that are absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract penetrate into the bloodstream.

The subclavian vein occupies an important place in the regulation of general and local blood circulation, as well as in the spread of various inflammatory processes occurring in the human body.

What diseases are associated with PV?

The circulatory system is considered a complex structure, which plays the role of transferring blood from other channels.

One of the common diseases of the subclavian vein is thrombosis, in which the blood flow along the entire upper limb changes significantly. The reason for the development of this disease lies in blood clotting disorders and excessive physical stress on the body.

Mostly the pathology is diagnosed in young patients and predominantly in men.

With timely diagnosis and effective therapy, the prognosis is quite favorable.

With high physical stress on the body, one arm becomes overstrained, which leads to compression of the veins. The result of this is thrombosis, and this is facilitated by increased blood clotting and too slow blood flow.

A common developmental anomaly of the subclavian arteries is the aberrant right subclavian artery. As a result of compression of the aberrant subclavian artery of the underlying structures, symptoms may appear that directly depend on the patient’s age and anatomical features of development.

Surgical interventions on the subclavian artery and brachiocephalic trunk

When the brachiocephalic trunk or subclavian artery is blocked in the area before the origin of the vertebral artery, retrograde blood circulation occurs behind the blockage, through the vertebral and also through the right carotid artery. Thus, in this situation, the just named vessels do not improve blood supply to the brain, but, on the contrary, “rob” it. Conform syndrome occurs. With functional load on the upper limbs, their need for blood flow increases, the outflow through the arteries of the upper limbs, vertebral arteries and the right carotid artery, which function as collaterals, increases, which further impoverishes the blood supply to the brain and aggravates ischemic symptoms.

There are many reasons for the phenomenon of “robbery”. Among the most common, as well as more clinically important, the following are known:

a) “stealing” from the left vertebral artery when the left subclavian artery is blocked;

b) general “stealing” of the right carotid artery and vertebral arteries during blockage of the brachiocephalic trunk; part of the blood drawn by the vertebral arteries can return through the right carotid artery back to the substance of the brain (“carotid return phenomenon”);

c) “stealing” the right vertebral artery when the right subclavian artery is blocked.

The subclavian artery, with an adjacent blockage, is characterized by a “stealing” symptom, going in two directions and giving a combined disorder of blood circulation to the brain and upper limb. This phenomenon is interesting because the withdrawal of blood (“stealing”) through the vertebral artery is accompanied by more severe symptoms than when this artery is blocked.

Indications for surgery for steal syndrome are primarily symptoms from the central nervous system. The blood supply to the upper extremities in most cases has enough time to compensate for the slow progression of the occlusion process due to the good development of the collateral network.

Operations for recanalization of the subclavian artery are indicated if

a) there are pronounced symptoms of disorders of the central nervous system;

b) ischemic symptoms develop in the upper limb when performing even minor work;

c) there is a combination of symptoms from the central nervous system and the upper limb.

In older patients with poor general condition, to reduce the onset of cerebral circulatory disorders, a simple ligation of the vertebral artery that interferes with blood circulation can be performed.

Isolation of the left subclavian artery

The middle part of the subclavian artery can be isolated on both sides from the supraclavicular approach. This access is convenient for applying a bypass shunt. It is very difficult to perform an endarterectomy from it. In addition, if necessary, the surgical field cannot be expanded from this access.

The incision is made transversely above and parallel to the clavicle, from the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the anterior edge of the trapezius muscle. The patient's scapula is retracted upward, which creates, due to the elevation of the clavicle, a more convenient approach to the subclavian artery. Under the platysma, at the lower edge of the wound, the external jugular vein, which flows into the subclavian vein, intersects between the ligatures. Excretion in fatty tissue, rich in small vessels and nerves, is quite difficult. The scapulohyoid muscle is retracted upward and outward, after which it is possible to navigate the deeper tissues. By palpating, the attachment site of the anterior scalene muscle and the first rib are determined, and the brachial plexus is found. In a triangle, the sides of which are the named anatomical formations, the subclavian artery passes between the subclavian vein and the brachial plexus. If there is a need for this, the clavicle is intersected, which allows for somewhat expanded access.

The peripheral part of the subclavian artery can be reached from the subclavian approach. For this part of the artery, the subclavian approach is more appropriate than the supraclavicular approach. With the subclavian approach, a large number of thin nerve branches are spared, which are often accidentally damaged, resulting in very unpleasant postoperative complications. After dissecting the skin and subcutaneous tissue, the pectoralis major muscle is easily separated along its fibers. After disconnecting the pectoralis minor muscle, you can easily find the neurovascular bundle in the fatty tissue. Its isolation is facilitated by raising and abducting the shoulder upward and anteriorly.

The initial part (orifice) of the subclavian artery on the left side is most easily reached through an anterolateral thoracotomy in the 1st II-IV intercostal space. To ensure good dilation of the thoracotomy wound, a roller is placed under the chest of the patient lying on the right side of the body, and the upper part of the operating table is raised. A large incision should be made, since it will be difficult to understand and act from a small incision in the “deep well” of the surgical wound. It is not difficult to navigate in the chest cavity to find the necessary vessel. The last major branch of the aortic arch is the left subclavian artery. It is placed on a holder after dissection of the mediastinal pleura and adventitia. This technique protects against possible damage to the clearly visible trunk of the vagus nerve and its posterior branch, the recurrent nerve.

Isolation of the initial part of the brachiocephalic trunk and the right subclavian artery

The ascending aorta is isolated from the median sternotomy. Its branch going upward, to the right and anteriorly is the brachiocephalic trunk.

Access to this vessel is crossed by one single formation located in loose fatty tissue (remnants of the thymus gland) - the left brachiocephalic (innominate) vein passing here. This vein should be isolated, if possible, atraumatically, over a wide area. It is taken on a rubber holder and easily moved to the side. The brachiocephalic trunk is found by its branching into the right carotid and subclavian arteries. During the isolation of the subclavian artery, it is necessary to remember the vagus nerve passing close here, going back behind the vessel of the branch of the recurrent nerve.

If access is intended to be continued to the carotid or subclavian arteries, then the incision is extended along the anterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle or in the transverse direction above the clavicle.

Isolation of the vertebral artery

The incision is made parallel to and above the clavicle in the same way as when accessing the middle part of the subclavian artery. Then the external jugular vein is crossed between the ligatures. If necessary, the sternocleidomastoid muscle can be incised. After this, the medial edge of the anterior scalene muscle is sought, along which the vertebral artery rises upward. When using a left-sided approach, care must be taken not to damage the thoracic duct. In addition, you should also be careful about the phrenic nerve running along the anterior scalene muscle. In the adjacent segment of the subclavian artery there are the orifices of the vertebral artery, the cervical-thyroid trunk and the internal thoracic artery.

The vertebral artery passes in the direction of the transverse process of the 6th cervical vertebra, converging medially, posteriorly and upward. It has no branches in this area!

Surgical interventions on the left subclavian artery

Stenosis or occlusion of the subclavian artery and brachiocephalic trunk, as a rule, is localized over a short distance of the initial (central) segment of these vessels.

First of all, they try to perform an endarterectomy. For this purpose, from the left-sided anterolateral thoracotomy, according to the method described above, these vessels are approached, isolated and taken onto a tourniquet. The opening of these vessels in the aortic region is isolated along with the corresponding section of the aortic arch so that a small section of the aortic wall can be squeezed out. At the same time, select the desired vascular clamp and apply it provisionally. The first branches of the subclavian artery, the internal mammary artery, the thyroid-cervical trunk and the vertebral artery are isolated and taken onto a tourniquet.

After applying a wall clamp to the aortic arch in the area of the mouth of the operated vessel, an arteriotomy is performed, moving slightly onto the aortic wall. An endarterectomy is performed in the layer required for this and, when indicated, the exfoliated distal part of the intima is fixed. The arteriotomy hole is closed with a continuous suture if possible, and only in the case of possible narrowing of the lumen of the vessel is plastic surgery with a synthetic patch applied. An important point is to remove all air from the recanalized vessel, since entry of air bubbles through the vertebral artery can cause cerebral embolism. Therefore, removal of the clamps from the vertebral artery is done last, after blood circulation in the vessels of the upper limb has been restored within 2-3 minutes. In cases where endarterectomy cannot be performed, a shunt is placed between the aorta and the subclavian artery from the same access. The prosthesis is sewn in at the border between the aortic arch and its descending part.

The literature on vascular surgery repeatedly describes a shunt between the carotid and subclavian arteries, but we do not recommend this operation. Surgical intervention involves placing a shunt between the common carotid artery and the subclavian artery from a small supraclavicular approach. If this operation is unsuccessful, it leads to the destruction of both of these vessels, leading to severe disorders due to a disorder of the blood flow of the carotid artery.

Surgical interventions on the brachiocephalic trunk and right subclavian artery

Difficulties and possible complications during this intervention on the brachiocephalic trunk and the right subclavian artery are associated with the fact that the common carotid artery departs from the brachiocephalic trunk. In some cases, during operations to maintain blood circulation in the carotid artery, it is necessary to use a shunt inserted into the lumen of the vessel. Access for surgery in this area is through a median sternotomy.

Due to the possible different localization of occlusion or stenosis, the following intervention methods are possible.

1. When the brachiocephalic trunk is occluded, this vessel is switched off by applying a clamp; the blood supply to the carotid artery is provided by reverse blood flow from the subclavian artery. The course of the operation is as follows: longitudinal arteriotomy, endarterectomy, closing the arteriotomy opening with a continuous suture, removing air from the lumen of the vessel. This particularly important measure, aimed at preventing the occurrence of embolism, is ensured by the sequential removal of the clamps and the gradual inclusion of branches in the blood circulation. The last, after 1-2 minutes, are the carotid and vertebral arteries.

2. In case of occlusion of the initial section of the subclavian artery with the transition of the atherosclerotic thrombus to the brachiocephalic trunk, the following intervention is performed. The brachiocephalic trunk, carotid and subclavian arteries are clamped. An arteriotomy is performed, extending to the brachiocephalic trunk and subclavian artery. Then a shunt is placed into the lumen of the brachiocephalic trunk and from it into the common carotid artery. After insertion of the shunt, you can safely, without fear of cerebral hypoxia, perform an endarterectomy. The arteriotomy hole is closed according to the method described above.

3. Closure of the initial section of the subclavian artery can be significantly complicated by narrowing of the mouth of the carotid artery by atherosclerotic plaque. With this double vascular lesion, a Y-shaped arteriotomy is performed through the mouths of the carotid and subclavian arteries and partially involving the brachiocephalic trunk. Since the length of the blockage is usually small, an endarterectomy is performed on the subclavian artery under the protection of a shunt inserted into the lumen of the vessel. A patch is applied to the arteriotomy hole at the end of the operation, which avoids narrowing of the lumen of these vessels.

4. When there is occlusion of only one subclavian artery, the operation is much simpler, since there is no need to insert a shunt into the lumen of the vessel. If access to the vessel is difficult, then the edge of the sternocleidomastoid and sternothyroid muscles is incised. After this, endarterectomy is performed according to all the rules.

If endarterectomy is not feasible, a bypass graft is performed. When closing the brachiocephalic trunk or subclavian artery, an aorto-subclavian shunt is applied. For this purpose, the wall of the ascending aorta is pressed out, and an end-to-side anastomosis is applied from a synthetic prosthesis.

Then an anastomosis is performed on the peripheral part of the subclavian artery. For this purpose, an incision is made under the collarbone, the peripheral part of the subclavian artery is isolated, and a tunnel for the graft is made behind the collarbone with a finger. The second anastomosis with the subclavian artery is performed in an “end to side” fashion.

Tests and diagnostic methods

To make an accurate diagnosis of vein damage, a specialist carefully studies the patient’s medical history. The doctor clarifies with the patient all the signs that bother the patient. The collected information allows us to clarify the duration of thrombosis.

In order to identify venous pathology in acute or chronic form, the following diagnostic methods are usually used:

- MRI and radiography help not only to identify the cause of the disease, but also the location of the thrombus;

- Ultrasound examination of deep veins;

- Dopplerography, which evaluates blood circulation in the damaged vein;

- X-ray using a contrast agent;

- duplex scanning of a vein;

- venography;

- shoulder girdle.

If puncture is necessary, subclavian access is preferably used.

Symptoms of PV pathologies

The main cause of subclavian vein thrombosis is considered to be high physical stress on the body. It is this factor that plays the leading role in the formation of a blood clot. Sometimes it is possible for a blood clot to break off, regardless of the degree of physical stress on the body, but this is extremely rare.

With thrombus formation in the subclavian vein, both increasing and disappearing symptoms may be observed, manifested by certain influxes.

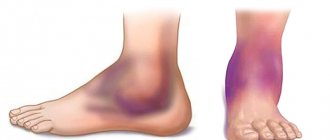

As a result of injury to the subclavian vein, certain symptoms are noted:

- pronounced pain in the arm area;

- too bright pattern of veins, visible through the epidermis;

- severe swelling of the limb and the appearance of a glossy sheen on the skin.

When the subclavian vein is injured, the patient exhibits signs of a neurological disorder. They manifest themselves in the form of numbness of the limbs and their twitching.

Often patients do not notice the appearance of a venous pattern on the arm. The diameter of the veins is determined by the size and increase in hypertension of the thrombus.

Initially, pain occurs during physical exertion on the body. Over time, discomfort can be constant and a feeling of fullness appears.

The pain syndrome is felt throughout the entire surface of the arm, in the shoulder area and collarbone. Sometimes it can radiate to the upper back and chest.

With thrombosis, the entire arm is affected by edema. When pressing on the swollen area, the hole in this area is not preserved. The hand becomes too hard and the unusual heaviness bothers you. With a prolonged inflammatory process, problems with blood circulation are noted, and the manifestations of thrombosis noticeably increase.

The patient may experience twitching of the fingers, a tingling sensation and a slight burning sensation.

During the transition of a patient's thrombosis from an acute to a chronic form, the clinical picture is blurred, and it becomes less pronounced. With this pathology, the patient’s motor activity is limited, muscle atrophy develops, and pain occurs with increased physical activity.

Sometimes, with a disease such as subclavian vein thrombosis, the patient is given a disability.

Acute venous thrombosis of the subclavian veins

Acute venous thrombosis of the subclavian veins (Paget-Schrötter syndrome) Paget-Schrötter syndrome is acute thrombosis of the subclavian vein

The syndrome is named after James Paget, who first proposed venous thrombosis causing pain and swelling of the upper extremities, and Leopold von Schrötter, who later associated the clinical syndrome with thrombosis of the subclavian and axillary veins (synonym: force thrombosis).

The incidence of this disease is 13.6-18.6% of the total number of patients with acute thrombosis of the vena cava and their main tributaries. Paget-Schretter syndrome most often occurs at a young age, mainly between 20 and 30 years. This pathology is more common in men. Right-sided localization of the process is observed much more often (2-2.5 times). Thrombosis of the subclavian vein in Paget-Schroetter syndrome is caused by chronic trauma to the vein and its tributaries in the area of the costoclavicular space (Fig. 1). The disease often occurs due to physical exertion in the shoulder girdle. Symptoms of the disease can appear both during normal work and after sleep.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the costoclavicular space.

Symptoms of Paget-Schroetter syndrome

The main symptom is swelling of the affected upper limb and, to a lesser extent, of the upper chest on the affected side.

One of the features of the disease is an acute onset and rapid progression, without any visible causes or warning signs, literally before our eyes, the entire limb swells and becomes cyanotic. Less commonly, clinical manifestations of the disease continue for 2-3 days. A characteristic feature of edema in Paget-Schroetter syndrome is the absence of a fossa after finger pressure.

Most often, patients are bothered by pain of varying nature and intensity in the limb, in the shoulder girdle, which intensifies with physical activity, as well as weakness, a feeling of heaviness and tension.

Dilatation and tension of the saphenous veins in the early stages of the disease are usually observed in the area of the cubital fossa. Subsequently, with a decrease in swelling, dilated veins are most pronounced in the area of the shoulder and forearm, shoulder girdle, and anterosuperior chest.

In most cases, the color of the skin of the upper extremities is cyanotic, less often pink-cyanotic. When you raise your hand up, the cyanosis decreases, and when you lower it, it increases.

A very important sign of Paget-Schretter syndrome is the discrepancy between pronounced local changes and the general condition of the patients. The body temperature is usually normal, the general condition of the patients does not suffer.

Diagnostics

The sudden onset of edema, cyanosis and numbness of the upper limb associated with exercise are the fundamental symptoms of this disease.

Today, the priority in diagnostics are ultrasound research methods: Dopplerography, ultrasound duplex scanning (USDS), ultrasound triplex scanning (UTS). The accuracy of the methods exceeds 90%. Non-invasiveness and safety allow it to be used repeatedly without causing harm to the patient.

A phlebographic study provides detailed information about the localization and extent of thrombosis of the axillary and subclavian veins, the compensatory capabilities of colateral blood outflow, and the etiology of the pathological process.

Treatment

In the acute stage, in severe cases, hospitalization of patients is indicated. Mild cases of the disease are treated on an outpatient basis.

The hand is fixed on a scarf, compression sleeves are used, and the hand is given an elevated position.

Drug treatment includes the prescription of antithrombotic agents, anti-inflammatory and analgesic drugs.

Various topical agents and physiotherapeutic procedures (short-wave diathermy, UHF currents, electrophoresis) are used locally.

Forecast

The prognosis for Paget-Schretter syndrome is favorable for life, but complete recovery does not occur. Complications of the disease in the form of pulmonary embolism and venous gangrene are extremely rare. Most of them retain residual effects of venous insufficiency of the limb, and only some patients return to their previous physical work. Most patients need to be transferred to easier work, and some of them need to be declared disabled.

In order to receive diagnostic and therapeutic assistance, patients with various diseases of the vascular system, including thrombosis of veins of various locations, can contact the Medical Clinical Center "Health" for an appointment with cardiovascular surgeons.

The arsenal of diagnostic capabilities includes ultrasonic triplex scanning (UTS), spiral computed tomography, modern x-ray surgical research methods (SCT, venography, etc.).

If indications are identified, the patient may be hospitalized in the inpatient department of the Moscow Clinical and Clinical Center "Zdorovye", in the department of cardiovascular surgery.

What doctors treat

A phlebologist treats vein pathologies, including the subclavian vein. It is he who can explain to the patient in detail what the subclavian vein is, its importance for the functioning of the whole body and possible pathologies.

If the blood vessels are not significantly clogged, the problem can be dealt with using local treatment. It is necessary that the hand is at rest.

When in a horizontal position, the upper limb should be positioned slightly above the heart area. While the patient is in an upright position, you need to suspend your arm using a scarf or bandage, bending it slightly at the elbow.

Therapy methods

Local therapy for damage to the subclavian vein can be carried out using certain groups of medications:

- gel-like products that contain rutoside and troxevasin;

- ointments with heparin;

- alcohol-based compresses;

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications.

In case of acute thrombosis of the subclavian vein and the appearance of painful symptoms, the patient is admitted to the hospital. The course of therapy includes the use of:

- angioprotectors;

- anticoagulants;

- antiplatelet agents;

- fibrinolytic agents.

The main goal of drug therapy for subclavian vein thrombosis is to restore normal blood circulation.

Causes and risk factors

Subclavian vein thrombosis is associated with compression of the thoracic outlet. The subclavian vein originates from the first rib from the axillary vein, and at the level of the sternoclavicular junction with the jugular vein it forms the brachiocephalic vein. Compression of the vein walls in the area between the collarbone and the first rib leads to slower blood flow and thrombosis. It can be considered the venous equivalent of thoracic outlet syndrome.

One of the causes of thrombosis is muscle hypertrophy (increase in the volume or mass of skeletal muscles). As a result, the subclavian vein can become compressed between the ribs (in front of it), the muscle (behind it), and the collarbone (above it).

Another reason is that a person has a congenital small anatomical space between the collarbone and the first rib. In this case, compression of the subclavian vein is possible even without major muscle hypertrophy.

Other causes of thrombosis include:

- incorrect posture,

- bone pathology (in the subclavian region),

- collarbone fractures

- use of subclavian catheters

- incorrect sleeping position

- thoracic outlet syndrome

- Risk factors include excessive physical activity. People who undergo intense physical activity and athletes (wrestlers, weightlifters or bodybuilders) have a higher risk of developing thrombosis due to repeated damage to the subclavian vein from frequent mechanical compression of the vessels between the collarbone, first rib and joint.

The average age of patients with Paget-Schroetter syndrome is 30-40 years, and the male to female ratio is approximately 2:1. It is more common on the right side, probably due to the frequency of right hand dominance, and 60% to 80% of patients have this condition. who performed vigorous exercise involving the upper limbs.

When is surgery required?

If after 2 months the blood clot has not resolved, then surgery is prescribed.

If thrombosis of the subclavian vein is too long, there is a high risk of necrosis of the arm tissue. During the operation, a specialist removes tissue that has died.

If blood circulation through the veins is impaired and there is a chronic form of thrombosis of the subclavian vein, thrombectomy or recanalization may be performed. If it is impossible to carry out this type of operation, they resort to eliminating the damaged section of the main vein, performing plastic surgery and bypass surgery.

In a situation where the pathology is completely untreatable, the arm is amputated.

Puncture and catheterization of the subclavian vein is performed by a surgeon or anesthesiologist. Sometimes these procedures can be performed by a specially trained therapist.

Indications for catheterization are inaccessibility of peripheral veins, too long operations with loss of large amounts of blood and the need for parenteral nutrition.

In case of injuries and bleeding, taking into account the topography of the subclavian vein, it is necessary to ligate it or apply a special bandage from three zones: under, above and behind the collarbone. The patient is placed on his back, a cushion is placed under his shoulders and his head is turned in the direction opposite to where the operation is being performed.

Ultrasound control during catheterization of central veins in children

Ultrasound scanner WS80

An ideal tool for prenatal research.

Unique image quality and a full range of diagnostic programs for an expert assessment of a woman’s health.

Introduction

Central venous catheterization is one of the necessary intensive care measures for critical illnesses. As a rule, doctors perform this operation based on knowledge of normal anatomy, guided by external landmarks (clavicle, sternocleidomastoid muscle, jugular notch, etc.). However, there are many factors that make it difficult to establish vascular access in patients in serious condition: body composition, hypovolemia, shock, congenital deformities and developmental anomalies. In this regard, the likelihood of such severe iatrogenic complications encountered during central venous catheterization, such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, lymphothorax and their combinations (in case of injury to the lung, vein, artery or thoracic lymph duct), remains quite high even when the procedure is performed by experienced specialists.

According to a number of foreign authors, mechanical complications during central venous catheterization occur in 5-19% of cases (David C. McGee, Michael K. Gould 2003).

Complication rates during central venous catheterization in children range from 2.5 to 16.6% for subclavian vein catheterization (James, Myers, Blackett et al.) and from 3.3 to 7.5% for internal jugular vein catheterization (Prince et al., Hall, Geefhuysen). According to our data, complications during catheterization of the internal jugular vein before the use of preliminary ultrasound examination (US) occurred in 11% of cases. All this prompted physician researchers to look for ways to visualize the suspected vein in order to reduce the incidence of complications.

Material and methods

More than 300 sick children undergoing central venous catheterization with emergency conditions caused by infectious diseases, aged from 1 month to 14 years, weighing from 2.6 to 62 kg, were examined. For the study, a SonoAce-Pico ultrasound scanner (South Korea) with color Doppler mapping capability and a microconvex sensor with a variable frequency from 4 to 9 MHz were used. In our practice, we used static and dynamic ultrasound guidance techniques.

Static technique: control ultrasound with visualization of the vessels of interest was performed immediately before puncture of the central veins, markings were applied to the skin before sterilization of the surgical field (Fig. 1). Ultrasound was performed in two mutually perpendicular planes in the transverse and sagittal (longitudinal) section between the legs of the sternocleidomastoid muscle when examining the internal jugular vein (Fig. 2, 3) and in the inguinal fold when examining the femoral vein. Using preliminary ultrasound, we determined the depth of the vein from the skin surface, the course of the venous trunk itself, the diameter of the vein, the diameter of the artery, the relative position of the vein and artery, the degree of contraction (collapse) of the internal jugular vein during inspiration in the presence of a hypovolemic state.

Rice. 1.

Preliminary marking of the location of the internal jugular vein.

Rice. 2.

Normal location and size of the internal jugular vein and carotid artery on cross-sectional examination.

Rice. 3.

Normal location and size of the internal jugular vein and carotid artery when examined in longitudinal section (the carotid artery is deeper than the internal jugular vein).

In young children, ultrasound and venous catheterization were carried out under general anesthesia (inhalation mask anesthesia with fluorotane or intravenous administration of ketamine in combination with Dormicum), in older children - under local anesthesia with a 1% lidocaine solution, and if necessary, sedation with Dormicum was performed. Catheterization of the central veins was performed using the Seldinger technique.

The dynamic technique differs from the static one in that a sterile sensor is installed on the surgical field and the puncture of the vessel is carried out under ultrasound guidance in real time. For the dynamic ultrasound guidance technique, we used both the above-mentioned SonoAce-Pico scanner and a special ultrasound scanner for catheterization of central veins Site-Rite 5 (manufactured by BARD Access, USA) with a linear multifrequency sensor from 5 to 11 MHz, equipped with a guide puncture needle. The sterility of the sensor in the area of the surgical field was maintained by placing special sterile disposable “sleeves” over the sensor or, as an alternative and cheaper option, using a sterile glove.

Results and discussion

Ultrasound data showed that of all the central veins, the internal jugular vein has the smallest depth (depth of location from 4 to 9 mm, regardless of the patient’s age).

We identified risk factors for unsuccessful punctures and catheterizations, regardless of the doctor’s experience. Such factors include anomalies in the development of neck vessels and the degree of collapse (reduction in vein diameter) during inspiration under conditions of hypovolemia.

Thus, in 3% of cases we were able to identify various anomalies in the size and location of the neck vessels, in the presence of which successful puncture and catheterization of the internal jugular vein was practically impossible. Anomalies were conventionally divided into anomalies in the size and location of blood vessels. Normally, the internal jugular vein is located more superficially and lateral to the carotid artery (see Fig. 2).

In case of anomaly in size, the normal location of the internal jugular vein and carotid artery was noted, but the diameter of the internal jugular vein was smaller than the diameter of the carotid artery (Fig. 4).

Rice. 4.

An abnormality in the size of the internal jugular vein in its normal location (the vein is smaller than the carotid artery and has a rounded appearance).

In case of anomaly of location, the reverse arrangement of the vessels was noted: the internal jugular vein was located deeper and medial in relation to the carotid artery. As a rule, the diameter of the internal jugular vein with an anomaly in the location of the vessels was significantly smaller than the diameter of the carotid artery (Fig. 5). All anomalies were one-sided.

Rice. 5.

Anomaly in the location and size of the internal jugular vein (the vein is located medial to the artery, its size is significantly smaller than the size of the artery).

In order to determine the diagnostic significance of the degree of reduction in the size of the internal jugular vein (collapse) during inspiration, we studied 10 healthy adults (medical personnel) and over time 50 sick children with severe volemic disorders: upon admission before infusion therapy and before transfer from the intensive care unit and intensive therapy after elimination of volemic disorders. We have found that in a healthy person without signs of hypovolemia, the internal jugular vein also tends to collapse during inspiration in a horizontal position, but the reduction in its size does not exceed 25-30%. At the same time, with severe symptoms of hypovolemia, the internal jugular vein collapses during inspiration by 50% or more, until the walls of the vein completely close. In patients with acute intestinal infections and dehydration without signs of acute respiratory failure, a collapse of the internal jugular vein during inspiration of more than 50% was regarded by us as a diagnostic criterion for hypovolemia. It is in close relationship with other diagnostic signs and data from instrumental studies. This sign corresponds to a decrease in central venous pressure of less than 1 cm of water column. and an increase in ejection fraction, according to echocardiography, more than 80%.

Methods for preventing collapse of the internal jugular vein include: positioning the patient during catheterization with the head end lowered (Trendelenburg position) and creating short-term excess pressure under the mask during anesthesia, which increases the blood supply to the internal jugular vein and its diameter by 25-50%.

If catheterization is performed in older children under local anesthesia and the child is able to cooperate with the doctor, then when performing the Valsalva maneuver, an increase in the diameter of the vein is noted by 1.5-2 times.

One of the problems when catheterizing central veins is the correct position of the central venous catheter, in which its end should be in the cavity of the superior vena cava above the right atrium. According to domestic and foreign researchers, incorrect position of the central venous catheter against the blood flow occurs in 0.5-18% of cases (5-18% with catheterization v. subclavia and 0.5-5% with catheterization v. jugularis interna) . The most common variant of incorrect position is the placement of the catheter in the cavity of the internal jugular vein during catheterization of the subclavian vein of the same name (Fig. 6). Currently, there are several methods for verifying the position of the central venous catheter: X-ray control, ECG control; One of them in practice is ultrasound to clarify the position of the central venous catheter (Fig. 7, 8).

Rice. 6.

Radiography. Incorrect position of the central venous catheter installed through the subclavian vein (the catheter is located against the blood flow in the internal jugular vein).

Rice. 7.

The same catheter in the lumen of the internal jugular vein during transverse scanning.

Rice. 8.

Central venous catheter in the lumen of the internal jugular vein (longitudinal scanning).

When testing the dynamic technique, the use of the Site-Rite 5 scanner “in one hand,” which is effective in adult practice, in young children was associated with a number of technical difficulties, despite good visualization of the vein and exact correspondence between the guide needle and its intended projection on the screen (Fig. . 9). In young children, due to the small size of the punctured vein (from 3.5 to 6 mm in diameter), when using this technique (see Fig. 9), it is difficult to clearly fix the operator’s hand, and therefore there is a high probability of part of the needle lumen coming out from a vein or, conversely, perforation of the far wall of the vein. Both of these can lead to penetration of the conductor into the paravasal tissue, which makes it impossible to insert the catheter into the vascular bed and can contribute to the formation of a neck hematoma, which complicates the task during subsequent punctures. Effective use of the dynamic technique, in our opinion, is only possible with the presence of an assistant (Fig. 10). When using the dynamic technique, we had experience in puncture of the internal jugular vein and installation of a central venous catheter through the external jugular vein and the pedicle of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and therefore we consider it advisable to carry out preoperative marking of anatomical landmarks: the location of the external jugular vein and the contours of the sternocleidomastoid - mastoid muscle.

Rice. 9.

Puncture of the internal jugular vein (dynamic technique) using a Site-Rite 5 ultrasound scanner.

Rice. 10.

Puncture of the internal jugular vein (dynamic technique) using an assistant and a SonoAce-Pico ultrasound scanner.

Currently, the discrepancy between the size of the sensor and the size of the surgical field in children weighing less than 5 kg, unfortunately, makes the effectiveness of using the dynamic technique in this group of patients very problematic.

conclusions

Preliminary ultrasound scanning revealed possible anomalies in the location of neck vessels in 3% of cases; in the presence of these anomalies, the risk of complications during puncture and catheterization of the internal jugular vein increases sharply.

Severe hypovolemia in infectious patients without signs of acute respiratory failure is manifested by a tendency to collapse of the internal jugular vein, which also serves as a risk factor for unsuccessful puncture. The use of techniques that increase intrathoracic pressure is effective for increasing the size of the internal jugular vein and for successful puncture and catheterization. A collapse of the internal jugular vein during inspiration of more than 50% can be considered a diagnostic criterion for hypovolemia in patients without signs of acute respiratory failure.

The introduction of ultrasound scanning into the central venous catheterization protocol made it possible to reduce the number of unsuccessful punctures by 50%, and the number of complications during catheterization of the internal jugular vein - from 11 to 1.5%.

Literature

- Ultrasound in Emergency Medicine O.J.Ma, J.R.Matier. BINOMIAL. 2007. 390 p.

- Ultrasonographic control of central venous catheterization. Jeffrey M. Rothschild. News of anesthesiology and resuscitation. 2007. N1. P. 49.

- Bykov M.V., Aizenberg V.L., Anbushinov V.D. Ultrasound examination before catheterization of central veins in children // Bulletin of intensive care. 2005. N4. P. 62.

- Subclavian vein catheterization: Ultrasound guidance allows less experienced clinicians to achieve better results. E. Gualtieri, SADeppe. Bulletin of Intensive Care. 2006. N4. P. 77.

Ultrasound scanner WS80

An ideal tool for prenatal research.

Unique image quality and a full range of diagnostic programs for an expert assessment of a woman’s health.