Causes of thrombosis

In order for a blood clot to form in a vein, a number of conditions or factors are necessary. In the classical version, there are three factors that contribute to thrombus formation (Virchow’s triad).

- hypercoagulable state (increased coagulability). There are many reasons for increased blood clotting - surgery on any part of the body, pregnancy, childbirth, diabetes, excess dietary fat, oral contraceptives, dehydration, genetic factors (rare), etc.

- injury to the inner wall of the vessel (endothelium). The vascular wall can be injured during the installation of a venous catheter, injection into a vein (due to this, thrombosis is very common in drug addicts who inject into the veins of the legs, in the groin), injuries, during radiation therapy, chemotherapy, etc.

- slowing down blood flow. It can be observed in various conditions - varicose veins, pregnancy, obesity, immobilization of a limb (for example, when wearing a cast after fractures), heart failure, forced sedentary position of the body (for example, during long air travel), compression of veins by tumors, etc.

Thrombosis can occur due to the action of one factor or a combination of them. For example, in case of a fracture of the leg bones, all three factors can be involved - increased coagulability in the case of extensive hemorrhages in the area of injury, damage to the vascular wall as a result of a mechanical shock, and a slowdown in blood flow as a result of wearing a cast.

Most often, thrombosis occurs in the veins of the lower extremities. This is due to the fact that stagnation most often occurs in these veins (obesity, varicose veins, edema, etc.).

Magnetic resonance imaging

Phase-contrast cine MRA can demonstrate the direction of portal venous flow and the presence of portal vein thrombus.

Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of the portal venous system accurately demonstrates thrombosis and collateral circulation.

Figure 6 : MRI shows intrahepatic dilation of the right lobe bile duct and a long stricture of the common bile duct.

Figure 7 : Contrast-enhanced T1 MRI showing thrombus in the portal vein and cavernous transformation of the portal vein.

MRI combined with dynamic three-dimensional imaging can not only detect portal vein occlusion, cavernous transformation, and gallbladder varices, but also depict bile duct abnormalities associated with portal biliopathy.

Shah et al compared MRI with intraoperative findings in the diagnosis of portal vein thrombosis in transplant candidates. In this study, the sensitivity and specificity of MRI for detecting underlying PVT were 100% and 98%, respectively. The reason for the discrepancy between MRI and transplant findings in 2 cases was a reduced caliber of the portal vein, which was interpreted as recanalized chronic thrombosis on MRI.

Superficial vein thrombosis

ATTENTION! Deep vein thrombosis is dangerous due to the detachment of a blood clot and its migration into the pulmonary artery (pulmonary embolism), which most often leads to serious consequences or instant death!

Superficial veins are affected by thrombosis most often with varicose veins. Blockage of the vessel is accompanied by inflammation of the surrounding tissues. That is why the terms “thrombophlebitis” (phlebitis - inflammation of a vein), “varicothrombophlebitis” (inflammation of varicose veins) are used for this type of thrombosis.

Usually, in the area of varicose veins on the lower leg, pain and redness appear along the vein; in the area of redness, the vein itself is palpated as a dense, painful “cord”. There may be a slight increase in body temperature. In general, thrombophlebitis of the superficial veins is not dangerous; there is no detachment of a blood clot with pulmonary embolism (with the exception of inflammation of the great saphenous vein on the thigh and the small saphenous vein in the popliteal region, this will be discussed below). With adequate treatment, the inflammatory phenomena subside, and the patency of the veins is partially or completely restored over time.

The great saphenous vein (GSV) runs under the skin from the ankle joint along the inner surface of the leg to the groin fold. In the groin it flows into the deep femoral vein. That is why thrombophlebitis of the GSV is dangerous due to the transition of thrombosis from the superficial (GSV) to the deep (femoral) vein - ascending thrombophlebitis of the GSV. But thrombosis of the femoral vein is dangerous due to the detachment of a blood clot and pulmonary embolism. Therefore, if there are signs of GSV thrombosis (redness, pain along the inner surface of the thigh), you should urgently consult a surgeon or call an ambulance. Such patients are hospitalized and, if there is a threat of thrombosis spreading to the femoral vein, the GSV is ligated closer to the groin - this is a simple operation under local anesthesia.

A similar situation, but much less frequently, occurs with thrombophlebitis of the small saphenous vein (SSV). It runs along the back of the leg and drains into the popliteal (deep) vein in the popliteal fossa.

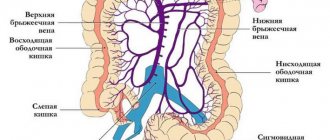

CT scan

The portal vein provides 75% of the blood flow to the liver. Consequently, peak liver contrast enhancement occurs during the portal venous phase, approximately 60 seconds after the start of the contrast bolus injection. With spiral CT, examining the liver takes about 20 seconds; images can usually be obtained in one go.

This technique can be extended to obtain dual-phase contrast-enhanced computed tomography, in which the liver is imaged twice with a single bolus of contrast agent, first during the arterial phase and then through the portal venous phase.

Dual-phase CT is indicated in selected cases involving benign or malignant lesions in which vascular characteristics indicate the correct diagnosis.

Figure 2 : Portal vein thrombosis. Portal venous phase enhanced axial computed tomography does not show blood flow in the portal vein. Note the multiple small lesions on the periphery of the right lobe of the liver.

Figure 3 : Portal vein thrombosis. Portal venous phase enhanced axial computed tomography obtained in the same patient as in the previous image shows a mass at the end of the splenic vein (arrow). Note the multiple small lesions on the periphery of the right lobe of the liver.

Figure 4 : Portal vein thrombosis. Portal venous phase enhanced axial CT scan obtained in the same patient as the previous 2 images shows an enlarged left gastric vein. No contrast enhancement is observed in the vein; this finding is suggestive of thrombosis (arrow).

Figure 5 : Axial contrast-enhanced CT image depicts cavernous transformation following portal venous thrombosis.

CT angiography or CT arterial portography may provide better delineation of the portal venous system and portal venous enhancement of the liver.

An angiographic catheter is placed into the common abdominal axis, hepatic artery, or superior mesenteric artery using a modified Seldinger technique through the femoral artery. Image acquisition begins 3-5 seconds after the start of contrast agent administration.

The examination must be completed as soon as possible before the contrast material is recirculated. To prevent significant artifacts related to the density of the contrast agent, use 70 ml of diluted (1-30%) iodinated contrast agent at an infusion rate of 2 ml/s.

On contrast-enhanced CT, PVT may be depicted as a poorly visualized center in the portal vein surrounded by peripheral enhancement. The attenuation of the portal vein is 20-30 HU less than that of the aorta.

Deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis is a more severe disease, usually requiring the patient to remain in the hospital.

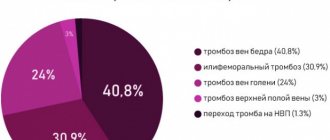

There are deep vein thrombosis of the leg, popliteal vein, femoral vein, iliofemoral (ileofemoral) thrombosis. Often there is damage to thrombosis of several sections (for example, the popliteal and femoral veins, deep veins of the leg and popliteal vein, etc.).

Deep vein thrombosis manifests itself primarily as swelling and moderate pain. Moreover, the higher the level of thrombosis, the more pronounced the edema. Thus, with thrombosis of the deep veins of the leg, there may be moderate swelling of the leg, sometimes the swelling is so insignificant that it is detected only when measuring the circumference of the leg (compared to the healthy leg). With thrombosis of the femoral or iliac (continuation of the femoral) veins, the entire leg, up to the groin, and in severe cases, the lower part of the abdominal wall swells.

In the photo - the left lower limb is cyanotic, thickened to the groin - deep vein thrombosis at the level of the iliofemoral segment (ileofemoral thrombosis).

Thrombosis, as a rule, is unilateral, so only one leg swells. Bilateral edema is observed with thrombosis of the inferior vena cava, deep vein thrombosis in both legs (which is quite rare).

Another symptom of thrombosis is pain. It is usually moderately expressed, pulling, sometimes bursting, is relatively constant in nature, and can intensify in a standing position. In case of deep vein thrombosis of the leg, the Homans, Lowenberg, Luvellubri, Meyer, Payra symptoms are positive.

With deep vein thrombosis, there may also be a slight increase in temperature, increased venous pattern, etc.

Treatment of thrombophlebitis of superficial veins

The main therapeutic measures are reduced to elastic compression (elastic bandage or compression hosiery) and the prescription of medications.

Medicines used include phlebotropic drugs (detralex, phlebodia), antiplatelet agents (thrombo-ACC), and anti-inflammatory drugs (Voltaren). Lyoton-gel is applied topically.

All patients require venous ultrasound to exclude concomitant deep vein thrombosis and clarify the prevalence of superficial vein thrombophlebitis.

Treatment of deep vein thrombosis

In almost all cases, deep vein thrombosis is treated in a hospital. An exception may be deep vein thrombosis of the leg, provided there is no threat of thromboembolism. The danger of thromboembolism can only be determined by ultrasound examination.

If deep vein thrombosis is suspected, the patient should be hospitalized immediately. In the hospital, an examination is carried out to clarify the prevalence of thrombosis, the degree of threat of pulmonary embolism, and treatment is started immediately.

Anticoagulants (anticoagulants), antiplatelet agents, anti-inflammatory drugs, and phlebotropic drugs are usually prescribed.

In case of massive thrombosis, in the early stages it is possible to carry out thrombolysis - the introduction of agents that “dissolve” thrombotic masses.

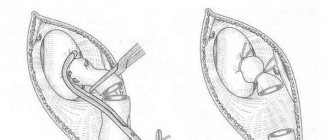

If there is a threat of thromboembolism, when the thrombus is attached to the vessel wall only in some part, and the tip of the thrombus “dangles” in the lumen of the vessel (floating thrombus), thromboembolism is prevented (installation of a vena cava filter, plication of the inferior vena cava, ligation of the femoral vein, etc. ).

The consequences of deep vein thrombosis vary. With a small thrombosis on the lower leg there may be no consequences. With massive thrombosis, especially “high” (at the level of the hip or above), swelling of the leg may persist for a long time, and in severe cases there may be trophic disorders, even the appearance of ulcers (post-thrombophlebitic disease (PTSD)). Therefore, after deep vein thrombosis, the patient is prescribed treatment for a long time in the form of elastic compression (special stockings), indirect anticoagulants (warfarin under the control of blood clotting), and other drugs.

You should see a phlebologist for at least six months after thrombosis.

In case of recurrent thrombosis, a genetic study is carried out; if the tests are positive, the issue of lifelong prescription of anticoagulants is decided.

Ultrasonography

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is increasingly recognized by ultrasound. Abdominal sepsis and decreased portal blood flow resulting from parenchymal liver disease are the main causes.

Figure 8 : Portal vein thrombosis. Longitudinal oblique sonogram of a 36-year-old woman with a history of Leber optic atrophy (hereditary optic neuroretinopathy) and alcohol abuse who had nonspecific complaints of malaise and vague abdominal pain. The image shows ascites and a bright liver (obesity). The portal vein has a linear echogenic structure running along the length of the portal vein (solid arrow). There is a cystic formation in the liver (open arrow).

Figure 9 : Portal vein thrombosis. Power Doppler of the liver shows blood flow around an intraluminal filling defect in the portal vein (P).

Figure 10 : Portal vein thrombosis. A spectral Doppler sonogram of the liver obtained from the same patient as in the previous image shows the portal vein (cursor) which does not demonstrate blood flow.

Figure 11 : Portal vein thrombosis. A longitudinal oblique sonogram was obtained from a 28-year-old woman who was referred for a gallbladder ultrasound. The image shows several vascular tubular structures at the porta hepatis, which are suggestive of cavernous transformation.

Figure 12 : Portal vein thrombosis. A color Doppler sonogram obtained from the same patient as in the previous image shows blood flow in the cavernous mass.

Figure 13 : Portal vein thrombosis. Color Doppler ultrasound of the spleen obtained from the same patient as in the previous 2 images shows mild splenomegaly with splenic varices. Endoscopic findings confirmed the presence of esophageal varices.

Figure 14 : Color Doppler ultrasound depicts a vascularized portal thrombus.

Figure 15 : Color Doppler ultrasound depicts a vascularized portal thrombus.

Figure 16 : Echoic partially recanalized portal vein thrombus. The patient is a 36-year-old woman with idiopathic chronic portal vein thrombosis of 2 years duration. She has cholestatic jaundice.

Sonograms may show echogenic lesions in the portal vein. A clot with variable echogenicity may be depicted. The clot is usually moderately echogenic, but if it has recently formed, it may be hypoechoic.

Patent vessels may have increased intraluminal echogenicity due to the accumulation of red blood cells, making slow blood slightly echogenic. Increased or decreased echogenicity may be observed in the lumen of the portal vein.

PVT eliminates the normal venous flow signal from the portal vein lumen during pulsed or color Doppler ultrasound. Color Doppler flow images can show flow around a clot that is partially blocking a vein. However, if the flow is slow, the Doppler signal may not be detected. Color flow may be present in other small collateral vessels.

Incomplete occlusion may occur. This is typical for tumor lesions. Alternatively, thrombolytic recanalization may occur. Cavernous malformations, spontaneous shunts, splenorenal and portosystemic collaterals can also be detected. The underlying cause may be obvious: hepatocellular carcinoma, metastases, cirrhosis, pancreatic neoplasms.

It is assumed that the thickening of the portal vein with a narrowing of its lumen is caused by portal phlebitis. This is considered a precursor to PVT in patients with acute pancreatitis. The diameter of the portal vein is greater than 15 mm in 38% of cases of PVT.

Causes of thrombosis in the superior vena cava system

The causes of thrombosis in the superior vena cava system are basically the same as other venous thrombosis. It may also develop as a complication of venous catheterization (cubital, subclavian catheter), sometimes arising as a result of prolonged compression or uncomfortable position of the upper limb (for example, during sleep).

The most common is thrombosis of the axillary or subclavian vein (Paget-Schrötter syndrome). Within 24 hours, swelling of the entire upper limb occurs with cushion-like swelling of the hand. There may be slight bursting pain. The color of the limb is unchanged or slightly cyanotic.

Practical Basics

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is increasingly recognized by ultrasound. Decreased portal blood flow caused by liver parenchymal disease and abdominal sepsis (ie, infectious or ascending thrombophlebitis) are the main causes.

PVT is a common complication of liver cirrhosis, and its prevalence increases with the severity of liver disease, ranging from 1% in patients with compensated cirrhosis to 8–25% in liver transplant candidates.

Correct diagnosis and characterization of PVT are important for prognosis and further treatment. Portal vein thrombosis is a poor prognostic indicator, found at diagnosis in 10-40% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Survival is approximately 2-4 months.

CEUS allows detailed visualization of the hepatic microvasculature, focal liver lesions, and portal vein thrombosis. Malignant thrombi have the same pattern of enhancement as the tumor from which they originated, including rapid arterial phase elevation and slow or weak washout in the portal vein.