General information

It is based on the formation of a blood clot (thrombus) in the mesenteric vessels, leading to blockage/reduction of their lumen. The blood supply to the small intestine/partially large intestine comes from the superior/inferior mesenteric artery, and the blood supply to the left half of the colon comes from the mesenteric artery. The outflow of blood from the intestines occurs through the superior/inferior mesenteric and splenic veins. The figure below shows the mesenteric vessels (branches of the mesenteric arteries/veins) that provide blood supply/outflow from the small intestine.

Thrombosis within the mesenteric circulation can occur in both arteries and veins (arterial thrombosis/venous thrombosis). Among occlusive lesions, thrombosis of mesenteric arteries accounts for 33.2-50.7%, and thrombosis of veins - 7.9-10.1%.

Mesenteric arterial thrombosis

The superior mesenteric artery is predominantly affected (85-90%), with the thrombus localized in the 1st segment (the mouth of the superior mesenteric artery). The inferior mesenteric artery is affected only in 10-15% of cases. The extent of intestinal damage is determined by the localization of the blood clot in the arteries. Accordingly, with thrombosis of the first segment of the superior mesenteric artery, acute ischemia / necrosis spreads to the entire small intestine, and in 50% of cases to the blind/right half of the colon; when the thrombus in segment II, ischemia / necrosis spreads to the terminal jejunum/ileum. When the thrombus is localized in segment III, only the ileum is affected.

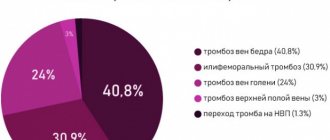

Mesenteric venous thrombosis is caused predominantly by a thrombus of the mesenteric veins and much less often by a thrombus of the portal vein. Highlight:

- primary (ascending) thrombosis, if the intestinal veins are initially thrombosed, and later large venous trunks; with primary thrombosis of the intestinal veins, limited lesions of the small intestine develop (up to 1 m);

- secondary (descending), if damage to the mesenteric veins occurs due to primary occlusion of the splenic/portal veins; it is characterized by the spread of the pathological process to the entire portal system with total necrosis of the small intestine.

Quite often, thrombosis of mesenteric venous vessels is combined with venous thrombosis of another location. Venous thrombosis extremely rarely leads to severe ischemia and venous infarction of the intestine ; they usually develop slowly and are accompanied by inflammation in the intestinal wall. However, against the background of primary arterial ischemia of the intestine, intestinal edema can quickly develop, which significantly complicates venous outflow and contributes to the formation of blood clots in the intestinal veins.

Thrombosis of the mesenteric vessels of the intestine develops, as a rule, against the background of hypercoagulation of the blood and a pronounced slowdown in blood flow, which is caused by damage to the vessel wall ( endarteritis , atherosclerosis , vasculitis ). Ischemic intestinal disease occurs predominantly in middle-aged/elderly people, equally common in men and women. Despite the relatively low incidence (0.9–1.2% of the total number of acute surgical pathologies of the abdominal cavity), acute mesenteric ischemia caused by thrombosis of the mesenteric vessels is accompanied by high mortality (in the range of 55–80%).

Depending on the location and type of thrombus (in relation to the lumen of the vessel - parietal, occluding, floating), a change in the state of mesenteric blood flow occurs in the form of compensation, subcompensation, slowly/rapidly progressive decompensation. Complete blockage of a vessel by a thrombus leads to a sharp decompensation of blood circulation and the development of ischemia / necrosis over a wide area.

Pathological changes in thrombosis of mesenteric vessels, depending on the severity/compensation of blood circulation, initially lead to the development of ischemia, and in cases of longer-term disturbance of intestinal blood flow, intestinal infarction , necrosis and peritonitis . At the earliest stages of thrombosis, only the mucous membrane is subject to ischemia, and with ischemia lasting more than 3 hours, destructive-necrotic processes develop, involving all layers of the intestinal wall, which leads to ischemic/hemorrhagic intestinal infarction. Damage to the entire intestinal wall contributes to the translocation of the infectious agent (bacteria) from the intestinal lumen into the abdominal cavity and arterial bloodstream, thereby contributing to the development of sepsis / peritonitis . In some cases, the situation is complicated by intestinal perforation as a result of intestinal infarction/necrosis, which causes the rapid development of peritonitis.

It should be remembered that thrombosis of the mesenteric vessels is an emergency condition that requires the fastest possible diagnosis and urgent medical care. With delayed diagnosis and the absence of urgent surgical intervention, acute intestinal ischemia quickly progresses to a state of irreversible necrosis , causing severe metabolic disorders, leading to the development of multiple organ dysfunction and death. Thus, late hospitalization (more than a day from thrombosis) significantly aggravates the condition of patients, and surgical interventions in most cases are ineffective.

BB system

The PV system includes all the veins that carry out the outflow of venous blood from the intra-abdominal part of the gastrointestinal tract, spleen, pancreas and gall bladder (see figure).

. Anatomical structure of the portal vein system. S. Sherlock, J. Dooley.

The PV is formed from the confluence of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins behind the head of the pancreas at approximately the level of the second lumbar vertebra; the length of the PV at the hepatic portal is 5.5–8.0 cm. At the porta hepatis, the PV is divided into the right and left lobar branches, corresponding to the lobes of the liver; further in the liver, the AV is divided into segmental branches accompanying the branches of the hepatic artery.

The BB does not contain valves in the main branches. The distribution of portal blood flow in the liver is not constant: blood flow to the left or right lobe of the liver may predominate. In humans, it is possible for blood to flow from the system of one lobar branch to the system of another. The pressure in a person's ventricular vein is normally about 7 mm Hg. Art. The volumetric velocity of blood flow through IVs reaches 1000–1200 ml/min [3].

Etiology and pathogenesis of PVT

According to modern concepts, venous thrombosis is the cumulative result of congenital or acquired procoagulant disorders and the action of local factors [10, 22].

A condition in which the balance between the processes of coagulation and fibrinolysis is disturbed in favor of coagulation processes can be defined as thrombophilia. A person with congenital or acquired thrombophilic disorders during life more often than in the normal population develops arterial or venous thrombosis of various locations (Table 1) [5, 11,12, 14, 23].

The Leiden mutation in the factor V gene occurs in 2–4% of the European population and leads to a change in the amino acid sequence of coagulation factor V itself (replacement of arginine with glutamine at position 506). Mutated factor V is resistant to destruction by protein C; constant circulation of activated factor V leads to uncontrolled synthesis of thrombin and the formation of blood clots [11, 13, 16, 23].

The mutation of the coagulation factor II gene was first described in 1996, occurs in the general population in 2% of the population and leads to excessive generation of prothrombin, i.e., a shift in hemostasis to the procoagulant side [17, 22].

Protein C is synthesized in the liver through a vitamin K-dependent mechanism and is a natural anticoagulant. Protein S is a cofactor of protein C, involved in the neutralization of active forms of coagulation factors V and VIII. Currently, about 160 mutations of the protein C gene and many mutations of the protein S gene have been described, which leads to a deficiency of these proteins and the development of thrombophilia [11].

Acquired blood coagulation disorders can occur in myeloproliferative diseases, antiphospholipid syndrome; they also accompany inflammatory and oncological diseases and are observed during the use of oral contraceptives [16, 22, 23], pregnancy and hyperhomocysteinemia. In 60% of patients with thrombosis of the veins of internal organs, hypercoagulation is observed, in 25% the influence of local factors is of paramount importance [16, 20] . PVT is characterized by a combination of causative factors [18, 20]. In approximately 20% of cases, the development of thrombosis does not find an exhaustive explanation [21]. The occurrence of thrombosis is promoted by all diseases that occur with a slowdown in blood flow through the liver.

The pathogenesis of PVT in cirrhosis is not fully understood. PH, a decrease in the rate of blood flow through IVs, and peripheral lymphangiitis and fibrosis may be important here [20].

. Causes of thrombophilia.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of thrombosis has been studied and is well described by Virchow's triad. The main links in thrombus formation are: damage to the vascular endothelium, changes in blood flow and hypercoagulation (violation of the rheological properties of blood), the development of each of which has its own reasons.

The formation of intravital blood clotting in a vessel occurs in several stages and includes platelet agglutination, fibrinogen coagulation, erythrocyte agglutination and precipitation of plasma proteins.

Risk factors for thrombosis

The following factors increase the likelihood of developing the disease:

- age over 50 years;

- obesity;

- smoking, alcoholism, drug addiction;

- poor nutrition;

- sedentary lifestyle;

- injuries;

- the need for frequent intravenous injections and procedures associated with violation of the integrity of blood vessels (blood sampling, hemodialysis, installation of a venous catheter) increases the risk of developing phlebitis and inflammation of the venous wall.

Causes

The immediate causes of a blood clot in the vascular bed of the mesentery are changes in the vascular walls against the background of slow blood flow and increased blood clotting. Indirect causes of the development of a blood clot in the arterial bloodstream of the intestine are: chronic heart failure , hypercoagulable processes , cardiosclerosis , endocarditis , vascular atherosclerosis , pancreatitis , trauma .

The causes of intestinal thrombosis in the venous vessels of the intestine are mechanical (strangulation of the mesentery, adhesions, volvulus), closed abdominal trauma with damage to the mesenteric veins/intestinal contusion, blood diseases (thrombocytosis), hemodynamic disorders, increased intra-abdominal pressure, taking oral contraceptives, portal hypertension , malignant neoplasms, destructive forms of pancreatitis , appendicitis , cholecystitis cardiac decompensation , taking hormonal drugs, Crohn's disease , ulcerative colitis , intra-abdominal infections of the abdominal organs, abscesses .

General information about thrombosis

Thrombosis

ー the process of intravital blood coagulation in the cavities of blood vessels and the heart. This process is also dangerous because part of the blood clot can break off and be carried by the bloodstream to other organs. For example, with thrombosis of the deep veins of the lower extremities, thromboembolism of the pulmonary artery or cerebral vessels often develops.

Symptoms

Symptoms of mesenteric intestinal thrombosis vary greatly and are determined by the stage of the disease. Thus, the reversible stage of intestinal ischemia is characterized by hemodynamic/reflex disorders. In most cases, acute circulatory disorders in the mesenteric vessels begin suddenly. With arterial thrombosis, prodromal phenomena can be observed (in 1/3 of patients), the cause of which is the formation of a blood clot/narrowing of the artery due to atherosclerosis , which is manifested by the appearance within 1-2 months of nausea, vomiting, periodic abdominal pain, bloating, and unstable stools.

Venous thrombosis in most cases develops more slowly (over 2-5 days). The stage of ischemia is manifested by an attack of sharp, predominantly constant, uncertainly localized abdominal pain, radiating to various parts of the abdomen. Less commonly, patients may indicate the presence of pain in the umbilical region or epigastrium. Nausea/vomiting appears, many patients experience 1-2 times loose stools, which occurs due to spasm of the intestinal loops, and only in 25% of cases does gas/stool retention occur immediately.

The characteristic behavior of patients is noted. Due to unbearable pain, patients cannot find a place for themselves, scream, ask for help, pull their legs to their stomach and take a knee-elbow position. Upon examination, patients have severe pallor of the skin. With a high localization of the thrombus in the superior mesenteric artery, an increase of 60-80 mm Hg is observed. Art. blood pressure (Blinov's symptom). The tongue is wet, the pulse is slow, the stomach is soft and painless. Leukocytosis in the blood .

In the absence of emergency surgical care, intestinal infarction . At this stage, the symptoms of intestinal thrombosis are complemented by intoxication and local manifestations (peritoneal symptoms) from the abdominal cavity. In the stage of a heart attack, the clinic is somewhat smoothed out: the intensity of the pain syndrome decreases, which contributes to a calmer behavior of patients; mild euphoria , expressed in inappropriate behavior of the patient; The pulse quickens and blood pressure normalizes. Diarrhea may develop , and vomiting . The tongue becomes dry. At this stage, blood may appear in the vomit/stool. Due to the appearance of effusion/bloating, the abdomen increases slightly in volume, but remains soft. The Shchetkin-Blumberg sign and muscle tension in the abdominal muscles are absent.

Unlike the ischemic , when the pain is diffuse in nature/localized in the epigastric region, the infarction stage is characterized by pain in the lower abdominal cavity, which is caused by the affected area of the intestine. In addition, upon palpation of the abdomen, local pain appears, which corresponds to the areas of intestinal infarction. Mondor's symptom is rarely encountered (on palpation of the abdomen, an inflamed intestine is identified as a dense formation without clear boundaries).

Intestinal necrosis and peritonitis develop quite quickly . At this stage, due to increasing intoxication, the patient’s condition sharply worsens, electrolyte imbalance, dehydration, and acidosis . Patients are adynamic, delirium may appear.

The specificity of peritonitis in acute circulatory disorders in the mesenteric vessels is the relatively late appearance of the Shchetkin-Blumberg symptom /muscle tension (compared to purulent peritonitis). Peritonitis begins to develop from below: diarrhea mixed with blood continues, some patients develop intestinal paresis, accompanied by gas/stool retention. The pulse is frequent, thread-like, up to 120-140 beats/minute, the blood pressure level decreases. The color of the skin is ashen-gray, dry tongue, high leukocytosis with a shift to the left. The course of intestinal peritonitis often ends in the death of patients after 2-3 days. Venous infarction is characterized by a longer course: 5-8 days. Much less often, the clinical symptoms are sparse with erased symptoms, which is more common in elderly/senile patients.

Disease prognosis

The outcome of thrombosis varies. Favorable ones include aseptic autolysis of a blood clot, which occurs under the influence of proteolytic enzymes of leukocytes. Small thrombi can be completely subjected to aseptic autolysis. More often, blood clots, especially large ones, are replaced by connective tissue, that is, they are organized. The ingrowth of connective tissue into a thrombus begins in the region of the head from the intimal side of the vessel, then the entire mass of the thrombus is replaced by connective tissue, in which cracks or channels lined with endothelium appear, the so-called. clot drainage. Later, the channels lined with endothelium turn into vessels containing blood; in such cases, they speak of vascularization of the thrombus, which often restores the patency of the blood vessel. However, the organization of a thrombus does not always end with its canalization and vascularization. Calcification of the thrombus and its petrification are possible; In this case, stones sometimes appear in the veins - phleboliths [3, 9, 10, 13].

Unfavorable outcomes of thrombosis include: • separation of a thrombus or part of it and transformation into a thromboembolus, which is a source of thromboembolism; • septic melting of a blood clot, which occurs when pyogenic bacteria enter the thrombotic masses, which leads to thrombobacterial embolism of the vessels of various organs and tissues (in sepsis). The prognosis for PVT is completely determined by the etiology of the disease. In adults with PVT, the 10-year survival rate is, according to various sources, 38–60% [9, 21]. Patients die mainly from complications of underlying diseases (cirrhosis, liver cancer). Mortality from bleeding from varicose veins in patients with PVT without cirrhosis does not exceed 5%, while in patients with cirrhosis this figure is 30–70% [9,21].

In conclusion, it should be noted that PVT is a serious disease that requires immediate diagnosis and intensive treatment in order to prevent complications, such as the formation of cavernous transformation and progression of PG. The survival of patients with portal thrombosis directly depends on the speed and thoroughness of diagnosis, the use of modern methods of instrumental and laboratory examination and visualization of thrombosis, and the assessment of concomitant thrombophilic conditions that increase the risk of complications. Early anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy promotes reperfusion of thrombosed areas of the veins of the portal system and, despite the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, is necessary for patients with PVT, as well as with diagnosed PG and cavernous transformation of VV.

Tests and diagnostics

Diagnosis of the disease should primarily be based on an analysis of clinical manifestations. Patients should be hospitalized at the slightest suspicion of acute disturbance of mesenteric circulation. The diagnosis must be made or completely rejected within the near future, since with long-term observation the condition of patients worsens significantly, and they become inoperable of peritonitis

The main diagnostic methods are angiography and diagnostic laparotomy. Selective angiography allows you to accurately determine the localization of occlusion, the type of blood flow disturbance, the extent of the lesion, and the presence/condition of collateral compensation pathways for blood flow. Angiographic diagnosis of blood flow disorders in mesenteric vessels is based on a comprehensive analysis of the arterial, venous and capillary phases of angiograms.

More complete information can be obtained by performing angiography in combination with laparoscopy. Diagnosis in the stage of ischemia is difficult, since it is necessary to base it on functional signs (lack of peristalsis, spasm of intestinal loops, etc.). Laparoscopic data allow us to accurately judge the extent of intestinal damage/degree of destruction of the intestinal wall. In later stages (infarction and peritonitis), laparoscopic diagnosis is mandatory.

Active differential diagnosis is necessary for diseases that in their manifestations may be similar to the symptoms of acute disorders of mesenteric circulation in the first hours of the disease ( myocardial infarction , pancreatitis , intestinal obstruction , etc.). The clinical picture of an acute abdomen can also be caused by inflamed mesenteric lymph nodes (mesadenitis).

Thrombosis in children

Possible causes of blood clot formation in children:

- thrombophilia - congenital deficiency of anticoagulant blood factors;

- leukemia, other oncological diseases;

- cutaneous fulminant purpura, disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome (develops with severe intoxication, inflammatory diseases: pancreatitis, peritonitis, etc.);

- the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, and other autoantibodies (antibodies to one’s own cells).

Episodes of blood clots in a child should prompt a serious examination to determine the cause.

Forecast

The prognosis of thrombosis of mesenteric vessels depends on the timeliness of surgical intervention. With delayed diagnosis/lack of urgent surgical intervention acute intestinal ischemia caused by thrombosis of mesenteric vessels progresses to a state of irreversible necrosis , causing severe metabolic disorders, leading to the development of multiple organ dysfunction and death. Surgical interventions after 12-24 hours after thrombosis of intestinal vessels are ineffective (postoperative mortality reaches 85-90%). More favorable results are observed after surgery on intestinal vessels in the first 4-6 hours (up to 75% of those recovered).

List of sources

- Pokrovsky A.V., Yudin V.I. Acute mesenteric obstruction // Clinical angiology: Guide / Ed. A. V. Pokrovsky. T. 2. M.: Medicine, 2004. P. 626-645.

- Savelyev V. S., Spiridonov I. V., Boldin B. V. Acute disorders of mesenteric circulation. Intestinal infarction: Guide to emergency surgery / Ed. B. S. Savelyeva. M.: Triada-X, 2004. pp. 281-302.

- Solomentseva T. A. Acute disorders of mesenteric circulation in a therapeutic clinic // Acute and emergency conditions in medical practice. 2011. No. 2. P. 8-14.

- Yushkevich D.V., Khryshchanovich V.Ya., Ladutko I.M. Diagnosis and treatment of acute disturbance of mesenteric circulation: current state of the problem // Med. magazine 2013. No. 3. P. 38-44.

- Katerina J.M., Kahan S. Emergency Medicine: Trans. from English - M.: MEDpress-inform, 2005. - 336 p.

Treatment of PVT

Management of patients with PVT depends on the onset of the disease (acute or chronic), clinical presentation, etiological factors leading to PVT, age and other factors. Complications of PVT - ascites, bleeding from PVT - are treated in the same way as for cirrhosis with PG.

In acute PVT, anticoagulant therapy is recommended, which leads to complete or partial restoration of the PVT lumen in 70–80% of patients [5, 12, 15].

Spontaneous thrombus lysis in PVT is possible, but is very rare. Anticoagulant therapy does not increase the risk of bleeding, but it reduces the risk of intestinal infarction, which is life-threatening. The recurrence rate of PVT varies from 6 to 40% [2, 21], so some authors recommend anticoagulant therapy for 6 months [10, 21].

Thrombolysis through a transhepatic approach for acute PVT is a method that avoids the side effects of systemic anticoagulant therapy. Thrombolysis can also be carried out systemically, especially in cases of acute total or subtotal occlusion of IVs [9, 10].

Unfortunately, there is still no clear practical guidance on the prescription of anticoagulants in patients with PVT. How to choose the right anticoagulant? What doses should be used? When to stop anticoagulant therapy? What contraindications exist for the use of anticoagulants? Large randomized trials are needed to answer these questions.

Surgical treatments include transhepatic angioplasty, thrombolysis followed by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), thrombectomy with local fibrinolytic infusion. If the patient is planning to undergo shunting, it is preferable to perform distal splenorenal shunting [5, 10]. Splenectomy should be avoided, since it itself is an etiological factor in the development of PVT. The main methods of medical and surgical treatment of PVT are presented in Table. 2.

. Basic methods of treating PVT.