The term “hydropericardium” refers to the accumulation of more than 50 milliliters of fluid in the pericardial cavity. Its normal amount is approximately 30 ml. Inflammation in the pericardium begins with pain and an audible pericardial friction noise. Next, the amount of fluid in the cardiac membrane increases.

- Etiology

- Pathogenesis

- Symptoms and diagnosis

- Treatment

- Complications and prognosis

The effect of pericardial effusion on blood dynamics significantly depends on the rate of its accumulation and the extensibility of the outer layer of the pericardium. If fluid accumulates at a rapid rate, severe hemodynamic changes may occur. And a gradual increase in the amount of fluid over a long time may not manifest itself in any way. Due to pericardial effusion, the filling of the heart with blood becomes more difficult, its inflow decreases, and stagnation occurs in the systemic circulation and, partially, in the small circulation.

Cardiac tamponade occurs when a large amount of fluid accumulates, which limits the filling of the ventricles and atria, congestion begins in the veins of the systemic circulation and a decrease in cardiac output until the blood circulation stops completely. Exudative pericarditis with cardiac tamponade is divided into two types: acute and subacute.

Etiology

The causes of cardiac tamponade can be:

- tuberculosis

- acute pericarditis (viral or idiopathic)

- influence of radiation

- malignant tumors

- systemic connective tissue diseases (SLE, rheumatoid arthritis)

- injury

- Dressler syndrome

- postpericardiotomy syndrome

Any disease that affects the pericardium can lead to the accumulation of fluid in its cavity. Acute cardiac tamponade can occur as a result of trauma, including iatrogenic injury during pacemaker installation, aortic rupture during dissection of its aneurysm, or cardiac rupture during myocardial infarction (MI). Subacute cardiac tamponade, as a rule, appears as a consequence of pericarditis (idiopathic or viral), with uremia or a tumor in the pericardium. In most cases, doctors cannot determine the cause of exudative pericarditis, even when surgery is performed.

Causes

Most often, cardiac tamponade is caused by the following factors:

- hemopericarditis due to damage to the integrity of the sternum and heart;

- rupture of dissecting aortic aneurysm;

- heart rupture due to myocardial infarction;

- hemorrhages during cardiac surgery;

- long-term course of chronic diseases (pericarditis, hemopericarditis, lymphoma, myxedema, systemic lupus erythematosus, cancer of the breast, lungs, etc.);

- renal failure developing during hemodialysis;

- taking anticoagulants;

- irradiation, etc.

Pathogenesis

According to the norm, between the layers of the pericardium there can be from 20 to 50 ml of fluid, which makes it easier for them to slide relative to each other. This liquid corresponds to blood plasma in its electrolyte and protein composition. If there is more than 120 ml of fluid there, this increases intrapericardial pressure, reduces cardiac output and provokes arterial hypotension.

Clinical manifestations correlate with the rate of fluid accumulation, its quantity, and characteristics of the pericardium. Symptoms of cardiac tamponade occur if fluid quickly accumulates and reaches an amount of 200 ml. If the rate of accumulation is slow, then symptoms may not appear, even if the fluid is already 1-2 liters. Increased intrapericardial pressure with fluid accumulation up to 5-15 mm Hg. is considered moderate, and more than this amount is considered pronounced. Diastolic filling of the ventricle due to increased pressure inside the pericardium is accompanied by an increase in pressure in the chambers of the heart and pulmonary artery, a decrease in stroke volume of the heart and hypertension.

Cardiac tamponade

Questions

Please try the following questions before continuing.

The answers, along with an explanation, can be found at the end of the article. Which of these signs help in diagnosing cardiac tamponade?

- pulsus paradoxus

- enlarged heart on chest x-ray

- akinesia of the left ventricular wall on echocardiography

- low voltage ECG waves

- dullness of heart sounds

The following is true regarding pericardial fluid:

- its presence always confirms the diagnosis of tamponade

- the normal volume of pericardial fluid is 15-20 ml

- Echocardiographic assessment of pericardial fluid volume is a strong predictor of hemodynamic catastrophe

- it has an exponential volume-pressure relationship

- pericardiocentesis has only a diagnostic role in the management of cardiac tamponade

The following is true regarding the management of cardiac tamponade:

- pericardiocentesis is indicated for all forms of cardiac tamponade

- treatment includes careful fluid resuscitation and inotropes

- Echocardiographic evidence of cardiac chamber collapse predicts a positive response to fluid administration.

- emergency drainage is indicated for tamponade with incipient cardiac arrest

- Once the pericardial effusion has been removed, inotropes and vasopressors should be discontinued.

Introduction

Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition. Claudius Galen (131-201 AD) first described pericardial hemorrhages in gladiators suffering from stab wounds to the chest, and the English physician Richard Lowe (1669) first described their physiology. It took another two hundred years for the term “cardiac tamponade” to be coined by the German surgeon Edmund Rose.

Today, cardiac tamponade is recognized as an important diagnosis to exclude cardiac arrest in international modern life support algorithms. With the increasing availability of bedside echocardiography, the rate of diagnosis of tamponade is likely to increase, and thus knowledge of its management is a fundamental skill for any emergency physician.

Definition

Cardiac tamponade is defined as the accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac, creating increased pressure in the pericardial space, which consequently impairs the pumping ability of the heart. As the pumping function of the heart becomes impaired, cardiac output and systemic perfusion decrease progressively, leading to critical organ dysfunction. A blood clot or tumor compressing the pericardium also leads to similar consequences.

It is important to note that the presence of a significant volume of fluid in the pericardial sac does not always lead to the development of tamponade. This occurs because slowly accumulating fluid allows physiological compensatory mechanisms to limit the rise in pericardial pressure and therefore prevent pump failure.

Therefore, pericardial effusion should be distinguished from tamponade as an anatomical condition implying the presence of abnormal fluid in the pericardial sac without hemodynamic compromise. Cardiac tamponade is a pathophysiological condition in which pericardial effusion is accompanied by signs of obstructive shock.

Pathophysiology of cardiac tamponade

Physiology of the pericardium

The pericardial sac consists of 2 layers of tough fibrous tissue that surround and protect the heart. The inner visceral layer is separated from the parietal pericardium by a small amount of lubricating pericardial fluid. There is usually about 15-50 ml of pericardial fluid produced by the visceral mesothelial cells, which is drained from the pericardium by the lymphatic system into the mediastinum and right side of the heart.

The pericardial layers surround the heart, fused around the points where large vessels enter the mediastinum. The visceral pericardium is fused with the epicardium on the inside. The fluid layers of the pericardial sac are necessary to buffer the heart from external influences, to reduce resistance during the movement of the heart walls, and to provide a barrier against infection from surrounding structures, especially the lungs.

Pressure-volume relationship

Fluid in the pericardial space is characterized by a pressure-volume relationship that varies depending on factors affecting the ability of the pericardium to compensate for changes in volume. When plotting the pressure-volume relationship, 2 distinct phases appear as shown in the figure.

If the fluid accumulates gradually, then in the first phase the increase in pericardial fluid volume causes only a small increase in pericardial pressure (graph A). This occurs because normal pericardial membranes can stretch to accommodate more fluid. During the second phase, the reserve volume, below which pressure changes are minimized by the compliance of the pericardial membranes, is exceeded and the pericardial pressure begins to rise more rapidly.

In addition, a number of factors influence the rate of increase in pressure in the pericardial space. Most important is the length of time over which the fluid accumulates. The rapid increase in fluid volume, usually due to bleeding caused by penetrating thoracic trauma or after trauma sustained during cardiac surgery, leaves little time for pericardial membranes to stretch, and the resulting increase in pericardial pressure will be rapid (graph B).

In an acute situation, as little as 150 ml of fluid can lead to cardiac tamponade. With chronic accumulation of fluid, the pericardial membranes can stretch significantly; the volume of the pericardial sac can reach 2000 ml in advanced cases.

Compliance of pericardial membranes may be reduced in certain situations, such as pericardial mesothelioma or scar after cardiac surgery. In such cases, the ability of the pericardial sac to compensate for the increasing volume of effusion is reduced. The nature of the fluid forming the pericardial effusion is also important. Blood, unlike transudates, coagulates in the pericardial space, transmitting pressure changes more easily, in particular to local areas of the heart adjacent to the thrombus, which contributes to the collapse of the heart chambers. Chronic effusions may become fibrous and more viscous, leading to a greater increase in pressure.

Stages of cardiac tamponade

The development of cardiac tamponade can be divided into early and late stages, with corresponding differences in the severity of hemodynamic disturbances and the extent to which compensatory mechanisms are able to maintain cardiac output. Tamponade will only develop if there is a progressive increase in pericardial pressure. A necessary condition for sustained pericardial hypertension is a volume of effusion that exceeds the volume of pericardial reserve and a rate of fluid accumulation that exceeds the rate of pericardial distension.

Early stage

In the early stages of cardiac tamponade, fluid fills the pericardial reserve volume and pericardial pressure begins to increase. The filling pressure of the right chambers of the heart is lower than in the left and primarily suffers with increasing pericardial pressure. As tamponade progresses, the filling pressure gradient of the cardiac chambers decreases, resulting in a significant decrease in venous return.

The right atrium and right ventricle are compressed and their diastolic filling is impaired, since the pressure of the right chambers is minimal in diastole. As the return of venous blood to the right atrium decreases, central venous pressure rises. Poor filling of the right ventricle results in an underutilized ventricle that operates at the lower end of the Frank-Starling curve. Underfilling and limited contractility result in low stroke volume.

Late stage

As pericardial pressure rises sufficiently to overcome the filling pressures of the left atrium and left ventricle, a sharp decrease in cardiac output occurs. Although there is a decrease in coronary blood flow, the mechanism of myocardial dysfunction in tamponade is usually non-ischemic. The process is accompanied by depletion of compensatory capabilities, with an increase in fluid retention, a decrease in cardiac output and venous return, leading to a state of obstructive shock and cardiac arrest.

Physiological compensatory mechanisms

The most important physiological compensatory mechanism is an increase in sympathetic tone. Tachycardia and sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction lead to an increase in systemic vascular resistance to maintain mean arterial pressure.

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is activated, causing fluid retention in the body. Increased central venous pressure improves diastolic filling of the right heart, but this has a limited effect. There are no changes in the level of atrial natriuretic peptide, since there is no distension of the heart chambers.

Causes

The causes of cardiac tamponade can be divided into surgical and therapeutic, generally corresponding to acute and chronic occurrence.

Bleeding after heart surgery

- Bleeding may occur from graft leakage or generalized capillary hemorrhage secondary to prolonged extracorporeal circulation time and coagulopathy. The risk of tamponade is higher with valve heart surgery than with coronary artery bypass grafting. Coronary injury can also occur during coronary stenting and vascular ballooning.

- Immediate/Acute; can be up to 2 weeks

Injury

- Penetrating trauma is more likely to cause tamponade than blunt trauma.

- Immediate

Aortic dissection

- Retrograde extension of aortic dissection may be complicated by bleeding into the pericardial sac, the prognosis is poor

- Acute onset

Malignant neoplasm

- Secondary to an underlying disease such as lung cancer, pericardial mesothelioma, or treatments (radiation therapy-induced pericarditis)

- Chronic course

Idiopathic

- Cause unknown

- Chronic course

Infections

- Viral, tuberculosis or HIV

- Acute/chronic course

Pericarditis

- Secondary in systemic vascular collagenosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, myxedema or uremia (pericarditis occurs with large pericardial effusion)

- Chronic course

Massive hydrothorax

- A sufficiently large pleural effusion can compress the heart and impair ventricular filling (rare)

- Acute/chronic course

Clinical manifestations

Cardiac tamponade can present in a variety of forms, from subtle and nonspecific to acute and easily noticeable. The key to prompt recognition of cardiac tamponade is maintaining a high index of suspicion in patients with early signs and initiating appropriate investigations.

Clinical signs of cardiac tamponade vary depending on the rate of progression and the underlying cause. The most common signs of shock—dyspnea, tachycardia, and hypotension—are less pronounced with tamponade. A thorough history and examination will help identify the underlying cause, including recent insertion of a pacemaker; chest pain reflects myocardial infarction or pericarditis; renal injury or a history of tuberculosis lead to uremic and inflammatory pericardial effusions, respectively.

Pericardial effusion associated with HIV infection should be suspected if there is a history of intravenous drug abuse or multiple opportunistic infections. Recent cardiac surgery, coronary intervention, or thoracic trauma are important causes of tamponade. A history of these events in combination with clinical signs requires urgent investigation.

The following clinical signs are especially important in the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade.

Beck's triad

Claude Beck, who later became a professor of cardiovascular surgery at Case Western Reserve University in the United States, first documented the three classic signs of acute cardiac tamponade in 1935. Its triad consists of hypotension, increased jugular venous pressure and muffled heart sounds. Although these signs are pathognomonic, they are not always fully present in patients with tamponade. In addition, the triad is more fully represented in surgical patients who have rapid onset of tamponade, as opposed to the slower onset of most therapeutic causes of tamponade, in which features of Beck's triad may not all manifest.

Paradoxical pulse

A more common finding that helps diagnose cardiac tamponade is the phenomenon of pulsus paradoxus. First described in 1873 by the German physician Adolf Kussmaul, pulsus paradoxus results from a drop in systemic blood pressure during the inspiratory phase of spontaneous ventilation. This phenomenon occurs due to negative intrapleural pressure increasing venous return to the right chambers of the heart, resulting in protrusion of the interventricular septum towards the left chambers of the heart.

A small respiratory change in venous return to the heart occurs under normal conditions, but this effect is exaggerated in cardiac tamponade. Inelastic pericardium during tamponade inhibits the movement of the ventricular walls and causes a sharper protrusion of the right ventricle towards the left. Left ventricular dysfunction is secondary to right ventricular dysfunction - this is called ventricular interdependence.

A paradoxical pulse with a difference of more than 10 mmHg between inspiratory and expiratory systolic blood pressure in a spontaneously ventilated patient is highly sensitive for detecting cardiac tamponade. The degree of change in blood pressure can also help predict the degree of cardiovascular impairment in a patient. Note that in a mechanically ventilated patient, the intrapleural pressure becomes positive and the pulse paradox pattern changes to the opposite, i.e. systolic blood pressure is higher during inspiration and lower during exhalation.

Reverse pulsus paradoxus occurs to some degree in all sedated mechanically ventilated patients and is a cyclic change in pulse pressure used as an indicator of fluid responsiveness. Right ventricular afterload increases with positive inspiratory pressure because the increase in alveolar pressure is greater than the increase in pleural pressure, hence the pulmonary capillaries are compressed and right ventricular ejection is impeded. However, left ventricular preload increases during mechanical inspiration as pulmonary blood is squeezed toward the left side of the heart.

Increased left ventricular preload, together with increased ejection fraction, resulting from positive inspiratory pressure, leads to an increase in left ventricular stroke volume and systolic blood pressure during the inspiratory phase. The long pulmonary transit time of blood (about 2 seconds) means that the reduced stroke volume of the right ventricle causes a drop in blood pressure only a few seconds later, during the expiratory phase.

Cardiovascular compromise may be aggravated by mechanical ventilation during cardiac tamponade, especially by high levels of positive end expiratory pressure, due to increased impairment of venous return to the right chambers of the heart. Also, Doppler studies of respiratory disturbances of cardiac blood flow may be inaccurate in diagnosing cardiac tamponade in a mechanically ventilated patient.

The absence of pulsus paradoxus should not be used as a criterion to exclude the diagnosis of tamponade. Cardiac tamponade is not the only cause of paradoxical pulsus. Severe asthma, pulmonary embolism, and tension pneumothorax may exacerbate pulsus paradoxus.

In patients with aortic regurgitation, the left ventricle may fill from the aorta during inspiration. Therefore, if aortic dissection causes both aortic regurgitation and cardiac tamponade, pulsus paradoxus may not be detected. Similarly, shunting for atrial septal defects can balance changes in venous return during inspiration, with similar effects.

Physiological compensatory mechanisms are often involved to maintain normal systemic blood pressure during the respiratory cycle, indicating that it is important to consider multiple trends and clinical features when diagnosing cardiac tamponade.

Survey

Tests performed to diagnose cardiac tamponade are mostly noninvasive and can be performed at the bedside.

The manifestations of tamponade present on chest x-ray and ECG are relatively nonspecific and do not differentiate between pericardial effusion and tamponade. Fluid in the pericardium can decrease electrical conductivity, resulting in decreased QRS voltage on the ECG. Cyclic variations in QRS amplitude on the ECG are more characteristic of tamponade and are known as electrical alternans. Sinus tachycardia is the most common rhythm with tamponade, but atrial arrhythmias caused by changes in atrial pressure may also be found.

Chest x-ray may reveal an enlarged cardiac shadow with a globular shape of the heart reflecting expansion of the pericardial sac with fluid. This sign is more typical for chronic causes of tamponade, when fluid accumulates gradually. Acute tamponade can occur without a change in cardiac size on chest x-ray.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is one of the most important tests for detecting cardiac tamponade. A solid pericardial effusion produces a classic pattern called “heart oscillation.” The heart oscillates from side to side within the pericardium, most significantly with large effusion, and the anatomical relationship between the heart and ECG electrodes also changes with a resultant effect on the QRS complex (the cause of electrical alternans).

Pericardial fluid can be visualized in several positions, including parasternal long axis, parasternal short axis, apical 4-chamber, and subcostal. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends looking for the following features to help diagnose tamponade:

- Diastolic collapse of the anterior free right ventricular wall, right atrium, left atrium. Very rarely, left ventricular collapse may occur.

- An increase in the thickness of the diastolic wall of the left ventricle, described as “pseudohypertrophy.”

- Dilation of the inferior vena cava without changing the size of the airways, indicating increased pressure in the right atrium.

ESC also recommends the use of M-mode echocardiography (motion-mode, in which the vertical axis from the ultrasound transducer is plotted against time on the X axis, allowing the representation of moving structures during the cardiac cycle) to detect large respiratory fluctuations in the mitral and tricuspid flow.

Poor hemodynamic tolerance to effusion is caused by an inspiratory rise of more than 40-50% in right-sided cardiac flows or a decrease of more than 25-40% in left-sided cardiac flows with an inverted E/A ratio across the mitral and tricuspid valves. The E/A ratio is the ratio of the early diastolic filling velocity of the ventricles to the higher late diastolic blood velocity caused by atrial contraction. The amount of effusion present can be assessed using the plarimetry function (zone assessment), found on most echocardiographic machines, but is not necessarily a predictor of hemodynamic compromise.

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) demonstrates tamponade by right atrial collapse with a sensitivity of 50-100% and a specificity of 33-100%. Right ventricular collapse has a sensitivity of 48-100% and a specificity ranging from 72-100%. Conversely, after cardiac surgery, TTE is more limited with a negative predictive value of 41%. Transesophageal imaging provides a better view of the posterior pericardial wall and is therefore critical in the diagnosis of retroatrial hematoma (a possible complication after cardiac surgery).

Differential diagnosis

Cardiac tamponade must be differentiated from other causes of acute heart failure, such as cardiogenic shock, in which primary myocardial dysfunction results from the heart being unable to produce adequate cardiac output to maintain systemic perfusion. The most common cause of cardiogenic shock is extensive myocardial infarction.

Constrictive pericarditis results in pericardial thickening and ventricular diastolic dysfunction and may mimic tamponade in the absence of effusion. Differentiating between tamponade and constrictive pericarditis can be difficult, but the main pathological influences on cardiac filling are pronounced. With tamponade, pericardial pressure is elevated throughout the cardiac cycle. In contrast, the myocardium does not contract in constrictive pericarditis while the heart dilates to fill the pericardium during diastole. Therefore, the normal two-level nature of the venous return to the heart is preserved in constrictive pericarditis, since compression of the heart does not occur during systole, whereas the venous return will be single-level and limited during tamponade. Skilled echocardiography can help distinguish between these conditions.

Also differentiated from massive pulmonary embolism and tension pneumothorax. Rarely, a tense pneumopericardium can mimic acute cardiac tamponade, but with the characteristic roar of millstones. This condition can be seen after penetrating chest trauma, esophageal rupture, and bronchopericardial fistula.

Therapy

Treatment of pericardial effusion can be divided into 2 groups: patients with incipient tamponade who are hemodynamically stable, and patients with established tamponade who are not stable. Unstable patients require emergency intervention. Since pressure caused by fluid within the pericardial sac is the main problem, the definitive treatment is drainage of the pericardial fluid to relieve myocardial compression.

Several approaches are available for pericardial drainage. In a life-threatening situation, the fastest and safest approach should be taken. Efforts should be made to involve cardiac surgery teams, but this is not always possible; therefore, doctors of all urgent medical specialties should be proficient in the technique of pericardial drainage.

Hemodynamic support

Intensive care of patients with tamponade prior to pericardial fluid drainage should follow the basic principles of airway, breathing, and circulatory support, taking into account the specific pathophysiology of cardiac tamponade. The patient requires oxygen supply. Intubation and mechanical ventilation should be avoided unless strictly necessary, as this will worsen heart failure with tamponade.

In mechanically ventilated patients, reduced positive end-expiratory pressure should be adjusted to avoid restriction of venous return. Invasive hemodynamic monitoring is required to continuously measure arterial and central venous pressure.

Role of liquid

Successful fluid resuscitation depends primarily on fluid resuscitation parameters (eg, cardiac index, organ perfusion, or patient symptom relief), the type of tamponade, and overall fluid balance. The effects of hypovolemia are especially pronounced during tamponade. A single bolus infusion is likely to be beneficial, especially in hypotensive settings (<100 mmHg). Excessive fluid administration may worsen ventricular coupling and reduce cardiac output. Fluid infusion is useful for mild cardiac compression; a single infusion bolus will not cause harm. Subsequent boluses should be carefully assessed with the knowledge that they are unlikely to provide benefit.

Role of inotropes/vasopressors

The hemodynamic goals of tamponade are to increase cardiac output by increasing chronotropic function, reducing afterload, and reducing right atrial compression. Isoprenaline, dopamine, and dobutamine are first-line inotropes because they have been shown to increase cardiac output during tamponade. All of them increase the metabolic demands of the myocardium and reduce the time of its perfusion, and, consequently, the risk of myocardial ischemia.

Small studies have shown that vasopressors such as norepinephrine improve mean arterial pressure with minimal myocardial strain and without changing cardiac index. Therefore, the doctor’s choice between inotropes and vasopressors is based on his familiarity with the specific drug and the balance of risks and benefits for each drug.

Drainage

Final resolution of tamponade is achieved only by drainage of the pericardial sac. Techniques for drainage may include pericardiocentesis or surgery. Rapid resolution of the low cardiac output state occurs after release of pericardial pressure, and the anesthesiologist should be prepared to rapidly reduce the infusion of inotropes or vasopressors to avoid excessive increases in blood pressure that may increase bleeding.

Pericardiocentesis

Pericardiocentesis involves placing a catheter percutaneously into the pericardial sac to drain fluid. The procedure can be performed using anatomical landmarks or under echocardiographic or fluoroscopic guidance. Pericardiocentesis is contraindicated in aortic dissection and relatively contraindicated in severe coagulopathy.

Typically, the Seldinger technique is used with a needle inserted between the xiphoid and left costal margins, tilted at a 15-degree angle under the costal margin, and then slowly advanced to the tip of the left scapula. A plastic catheter is passed through a J-shaped guidewire. ECG monitoring is necessary because the instrumentation may touch the heart and provoke ectopic beats or ventricular arrhythmias.

Pericardiocentesis has both therapeutic and diagnostic value. Using this method, chronic pericardial effusion can be obtained for analysis, and subsequently sent for histological and biochemical examination if a malignant or inflammatory cause is suspected.

Complications of pericardiocentesis include puncture and rupture of the myocardium or coronary vessels. This can cause arrhythmia or myocardial infarction. The stomach, lungs or liver may also be punctured. Infection of the pericardial membranes may occur. These complications are rare, occurring in less than 5% of cases, and it is important to be familiar with the technique of pericardiocentesis as a potentially life-saving procedure.

Surgical drainage

Emergency sternotomy is indicated for tamponade with incipient cardiac arrest. This may be required in the emergency department or intensive care unit if time is insufficient or the patient is too unstable to be transferred to the operating room. Equipment for emergency thoracotomy should be available in these locations. A small subxiphoid incision is made, which can relieve some of the pericardial pressure before direct visualization and incision of the parietal pericardium. This is followed by drainage of fluid and control of bleeding within the pericardium. Ideally, cardiopulmonary bypass equipment and a trained perfusionist should be present.

Other surgical approaches to pericardial drainage are available, but there are no data from prospective randomized controlled trials to demonstrate their benefits. The video-assisted thoracoscopic approach is less invasive and creates a drainage window between the pericardium and pleura. However, it requires longer operating time and is associated with high perioperative morbidity.

Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy can be performed under local anesthesia in the cardiac catheterization laboratory and involves insertion of a balloon into the parietal pericardium using a subxiphoid approach under x-ray guidance. This procedure is more suitable for patients with therapeutic tamponade suffering from malignant effusions for whom surgery is contraindicated.

Postoperative care for these patients is managed in the intensive care unit because recurrence of tamponade may occur and organ support, including inotropes for compromised myocardium, may be required.

Summary

- Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening cause of obstructive shock.

- Tamponade can occur as a complication of a number of medical procedures, as well as during trauma or cardiac surgery.

- When the diagnosis is suspected, urgent echocardiographic confirmation of tamponade should be performed.

- Echocardiographic findings—right chamber diastolic collapse and ventricular coupling—are highly specific for cardiac tamponade.

- Therapy includes careful resuscitation of fluid and inotropes, but this does not replace definitive drainage through percutaneous or open surgical techniques.

Answers on questions

A high clinical suspicion is important, especially in combination with clinical symptoms such as muffled heart sounds, pulsus paradoxus, and low wave voltage on the electrocardiogram. Chest radiographs are rarely used in acute diagnosis.

Fluid in the pericardial space will not cause tamponade if it is kept at low pressure, as shown in the volume-pressure graph. Normal fluid volume is about 15 ml; a rapid increase in volume to 150 ml can impair cardiac function. Pericardiocentesis is both a therapeutic and diagnostic procedure.

Pericardiocentesis should be used with caution in cardiac tamponade following aortic dissection. Fluids and inotropes act as bridges to drainage, and anesthesiologists should be prepared to quickly stop the infusion after tamponade is relieved.

Peter Odor Andrew Bailey St. George's Hospital, London, UK

2013

Symptoms and diagnosis

Pericardial effusion can be diagnosed by fluorographic (x-ray) examination or echocardiography. Its presence is suspected in those diagnosed with chest or lung tumors, uremia, unexplained cardiomegaly, or increased venous pressure with an unknown cause.

As already noted, with the gradual accumulation of fluid in the pericardial cavity, there are no specific human symptoms and complaints. An objective examination, as a rule, does not provide the necessary information. When a large amount of fluid accumulates, the doctor may detect an expansion of the boundaries of relative cardiac dullness in all directions, a decrease and disappearance of the apical impulse. Kussmaul is also typical, which manifests itself as an increase in swelling of the jugular veins during inspiration.

In case of acute cardiac tamnonade, there may also be no complaints, or they are not typical for this diagnosis:

- increasing shortness of breath

- heaviness in the chest

- periodic fear

- sometimes dysphagia

Later, confusion and an excited state may appear. During the examination, swollen neck veins, shortness of breath, tachycardia, and dullness of heart sounds are found. Using percussion, the expansion of the borders of the heart is recorded. Without emergency pericardiocentesis, the patient loses consciousness and dies.

With subacute cardiac tamponade, patient complaints may be associated with the underlying disease and compression of the heart. With pericarditis of an inflammatory nature, myalgia, fever, and arthralgia are recorded in most cases before the disease. If pericarditis is associated with a tumor, the disease is preceded by complaints associated with this disease.

Examination reveals swelling of the neck and face. In most cases there is no chest pain. With significant effusion, there may be manifestations associated with compression of the esophagus, lungs, trachea, and recurrent laryngeal nerve by the effusion (cough, dysphagia, shortness of breath, hoarse voice).

During examination, doctors detect increased venous pressure, arterial hypotension, and tachycardia. A typical manifestation is pulsus paradoxus. With a calm inhalation, the pulse amplitude decreases significantly; or systolic pressure decreases during deep inspiration by more than 10 mm Hg.

These phenomena are interpreted as follows: during inspiration, there is an increase in venous return to the right ventricle with some deposition of blood in the pulmonary vascular bed; with a large pericardial effusion during inspiration, an increase in the amount of blood in the right half of the heart when it is impossible to expand within the pericardial sac leads to compression of the left ventricle, which is often accompanied by a decrease in its volume. The classic manifestation of cardiac tamponade is Beck's triad: dilatation of the jugular veins, arterial hypotension and muffled heart sounds (“small quiet heart”).

Signs of stagnation in the systemic circulation are rapidly increasing: doctors detect ascites in the patient, enlargement and tenderness of the liver.

An informative diagnostic method is an ECG. A decrease in the voltage of the 0#5 complexes is recorded, which occurs with a significant accumulation of fluid in the pericardial cavity. EchoCG is the most specific and sensitive method for diagnosing pericardial effusion. 2D mode allows detection of fluid in the pericardial zone. With its small accumulation, a free space appears behind the posterior wall of the left ventricle. If there is not much fluid, in the pericardial cavity there is a free space behind the posterior wall of the left ventricle more than 1 cm thick and its appearance in the area of the anterior wall, especially during systole. Echocardiography reveals two main signs of tamponade: compression of the right atrium and diastolic collapse of the right ventricle.

The next informative diagnostic method is chest x-ray. The contours of the heart are normal if little or moderate amounts of fluid have accumulated. Cardiomegaly is observed with a significant volume of fluid in the pericardium. There may be a straightened left heart contour. Sometimes the heart may become triangular, possibly reducing its pulsation.

Sometimes doctors do a test of the pericardial fluid to determine the cause of the fluid buildup. A puncture is performed and the resulting fluid is analyzed for the presence of bacteria, fungi, and tumors. The cytological composition of the fluid is studied, the amount of protein and the activity of lactate dehydrogenase are determined.

Differential diagnosis of cardiac tamponade and rheumatic diseases is necessary. To do this, the liquid is examined for antinuclear AT and LE cells.

Emergency care and treatment

Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition in which urgent pericardiocentesis or surgical intervention is indicated for emergency evacuation of transudate from the pericardial sac. In cases of tamponade caused by trauma or postoperative complications, the decision is always made to perform pericardiotomy or subtotal pericardiectomy.

Pericardial puncture is performed under constant monitoring of echocardiography or radiography and monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate and central venous pressure. Local anesthesia is used to numb this procedure. The resulting fluid is sent for bacteriological and cytological examination, and antibacterial, hormonal or sclerosing drugs can be injected into the pericardial sac (depending on the indications).

If necessary, a special catheter can be installed in the pericardial cavity to ensure normal outflow of transudate that continues to accumulate. At the next stage, the patient receives maintenance infusion therapy with nootropic drugs or plasma substitutes and treatment of the disease that provoked cardiac tamponade.

If there is a high risk of recurrent tamponade, pericardiotomy or subtotal pericardiectomy is performed. Also, these emergency surgical interventions are performed when there is compression of the heart caused by rupture of the myocardium or aorta. During pericardiotomy, the surgeon makes a hole in the pericardial wall (pericardial window), which ensures the outflow of transudate and allows inspection of its internal surface to identify foci of hemorrhage or tumor.

When performing a subtotal pericardectomy, which is performed for scar changes, calcification of the pericardium and chronic progressive exudative pericarditis, the pericardium is resected and only a small area of the pericardium adjacent to the posterior surface of the heart is left. After removal of the scarred pericardium, the heart is covered with pleural sacs or mediastinal tissue.

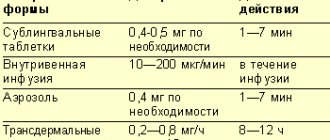

Treatment

Exudative pericarditis with cardiac tamponade is treated in a hospital. It is advisable to take into account the nature of the disease. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prescribed in moderate dosages are an effective treatment. This treatment is also carried out for dry pericarditis. Glucocorticosteroids are also sometimes used. Prednisolone is effective in a dose of up to 60 mg/day, it is taken for 5 to 7 days, then the dose is slowly reduced. Thanks to this drug, the effusion quickly resolves. If during 2 weeks of treatment with glucocorticosteroids (GC) there is no expected effect, a large amount of effusion is present, then a pericardial puncture is performed with the introduction of GC into the cavity of the cardiac sac. The management of the patient also depends on the volume of fluid in the pericardial cavity. If the amount of fluid is small, no therapy is required.

To improve hemodynamics in case of hypotension, liquid is administered - plasma, colloidal or saline solutions in an amount of 400-500 ml intravenously. The effectiveness of these measures is monitored by increasing systolic pressure and systolic ejection. Whatever type of cardiac tamponade is detected, it is necessary to puncture the pericardium in a timely manner. Often this is what helps to significantly improve the patient’s condition.