Angina pectoris, or as it is colloquially called “angina pectoris,” is one of the forms of coronary heart disease (CHD). Manifests itself in the form of pressing, squeezing or burning pain in the chest area. Pain can spread to the left arm, lower jaw, neck, and left subscapular region.

An attack of pain can be triggered by:

- physical activity (even if you just walked quickly or climbed the stairs);

- increased blood pressure;

- rapid heartbeat;

- inhaling cold air;

- emotional overstrain;

- an overly filling lunch.

Usually the pain goes away after a few minutes if you sit or lie down quietly, or after 2-3 minutes if you take nitroglycerin under the tongue.

Pathogenesis

In most cases, angina is caused by atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries of the heart; the initial stage of the latter limits the expansion of the artery lumen and causes an acute shortage of blood supply to the myocardium with significant physical and/or emotional stress; severe atherosclerosis, narrowing the lumen of the artery by 75% or more, causes such a deficiency even at moderate stress.

The occurrence of an attack is facilitated by a decrease in blood flow to the mouths of the coronary arteries (arterial, especially diastolic hypotension of any origin, including medicinal, or a drop in cardiac output due to tachyarrhythmia, venous hypotension); pathological reflex effects from the biliary tract, esophagus, cervical and thoracic spine with concomitant diseases; acute narrowing of the lumen of the coronary artery (non-occlusive thrombus, swelling of atherosclerotic plaque).

The main mechanisms for subsiding an attack:

- rapid and significant decrease in the level of work of the heart muscle (cessation of exercise, the effect of nitroglycerin);

- restoration of adequacy of blood flow to the coronary arteries.

Basic conditions for reducing the frequency and stopping attacks:

- adaptation of the patient's exercise regime to the reserve capabilities of his coronary bed;

- development of circuitous blood supply pathways to the myocardium;

- subsidence of manifestations of concomitant diseases;

- stabilization of systemic circulation;

- development of myocardial fibrosis in the zone of its ischemia.

Treatment of angina

Two main areas of treatment for angina pectoris:

- preventing the development of myocardial infarction, which can lead to sudden death,

- reducing the frequency and intensity of exacerbations.

Groups of drugs used for treatment:

- blood thinners,

- lowering cholesterol levels,

- reducing heart rate,

- preventing the development of arrhythmia,

- correcting blood pressure levels,

- dilating blood vessels of the heart.

This list includes nitrates and nitrate-like products.

If drug therapy is ineffective, surgical interventions are performed: coronary artery bypass grafting, stenting and balloon angioplasty.

Symptoms, course

With angina, pain is always characterized by the following symptoms:

- has the nature of an attack, that is, it has a clearly defined time of onset and cessation, subsidence;

- occurs under certain conditions and circumstances;

- begins to subside or completely stops under the influence of nitroglycerin (1 - 3 minutes after its sublingual administration).

Conditions for the occurrence of an attack of angina pectoris: most often - walking (pain when accelerating, when climbing a mountain, during a sharp headwind, when walking after eating or with a heavy load), but also other physical effort, and/or significant emotional stress . The conditioning of pain by physical effort is manifested in the fact that as it continues or increases, the intensity of the pain inevitably increases, and when the effort stops, the pain subsides or disappears within a few minutes.

The above three features of pain are sufficient to make a clinical diagnosis of an attack of angina and to distinguish it from various pain sensations in the heart and generally in the chest that are not angina.

It is often possible to recognize angina pectoris at the first visit of the patient, while to reject this diagnosis requires observation of the course of the disease and analysis of data from repeated questions and examinations of the patient. The following signs complement the clinical characteristics of angina, but their absence does not exclude this diagnosis:

- localization of pain behind the sternum (most typical!), rarely - in the neck, in the lower jaw and teeth, in the arms, in the shoulder girdle and shoulder blade (usually on the left), in the heart area;

- the nature of the pain is pressing, squeezing, less often - burning (like heartburn) or the sensation of a foreign body in the chest (sometimes the patient may experience not pain, but a painful sensation behind the sternum and then he denies the presence of pain itself);

- simultaneous with an attack of increased blood pressure, pallor, perspiration, fluctuations in pulse rate, the appearance of extrasystoles.

All this characterizes angina pectoris. The thoroughness of the medical questioning determines the timeliness and correctness of the diagnosis of the disease. It should be borne in mind that often a patient, experiencing sensations typical of angina, does not report them to the doctor as “not related to the heart,” or, on the contrary, focuses on diagnostically minor sensations “in the area of the heart.”

Angina at rest, in contrast to steiocardia at exertion, occurs independently of physical effort, more often at night, but otherwise retains all the features of a severe attack of angina pectoris and is often accompanied by a feeling of lack of air and suffocation.

In most patients, the course of angina is characterized by relative stability. This is understood as a certain duration of occurrence of signs of angina, attacks of which during this period have changed little in frequency and strength, occur when the same or similar conditions occur, are absent outside of these conditions and subside under conditions of rest (angina pectoris) or after taking nitroglycerin. The intensity of stable angina is classified by the so-called functional class (FC).

IFC includes persons whose stable angina is manifested by rare attacks caused only by excessive physical stress. If attacks of stable angina pectoris also occur during normal loads, although not always, such angina is classified as FC II, and in the case of attacks during light (domestic) loads, it is classified as FC III. IV FC is recorded in patients with attacks with minimal loads, and sometimes in their absence.

Angina pectoris should alert the doctor if: an attack occurs for the first time, but especially if attacks that occur for the first time become more frequent and intensify from the very first weeks of the illness; the course of angina pectoris loses its stability: the frequency of attacks increases, they occur in conditions other than before (at lower loads, stress), they also appear outside of stress (at rest, in the early morning), as if they move from FC I - II to FC III - IV FC; that is, the course of angina has changed, acquiring significantly new characteristics.

ECG changes (decreased ST segment, T wave inversion, arrhythmias), as well as a slight increase in the activity of serum enzymes (CPK, LDH, LDH1, AST), are usually absent in such cases, but the presence of these signs additionally confirms the instability of angina. Pre-infarction angina does not always result in heart attack (the probability of developing a heart attack is about 30%); this must be taken into account in clinical diagnosis.

Occasionally, the so-called variant (vasospastic) form of angina occurs, characterized by the spontaneous nature of the attack, sharp rises in the ST segment recorded on the ECG, refractoriness to beta blockers (anaprilin and obzidan), but sensitivity to calcium ion antagonists (verapamil, phenigidine, corinfar).

The basis for the diagnosis of any of the forms and variants of the course of angina pectoris is a correctly constructed and carefully conducted questioning of the patient. In unclear cases, a test with physical activity (bicycle ergometer test) is performed in order to identify hidden coronary insufficiency. The tactics for establishing a diagnosis are determined by the following schematic sequence of solving the main issues:

- Is the nature of the pain coronary (anginal)?

- Are there signs of pre-infarction angina?

- Is the current exacerbation during coronary heart disease related to the influence of extracardiac (concomitant) diseases?

Only a convincingly reasoned negative answer to the first of three questions gives the right to search for another cause (source) of pain: the discovery of another disease in a patient as the source of his pain cannot exclude the presence of simultaneous attacks of angina pectoris as a manifestation of coronary heart disease. About pain in the heart area of a non-anginal nature ( see Cardialgia.)

Complications of angina pectoris itself are not observed if it does not become an expression of the progression of cardiosclerosis and if it does not turn out to be the first manifestation of a developing myocardial infarction. Therefore, an attack of angina pectoris that lasts for 20 - 30 minutes, as well as unstable angina pectoris, require an electrocardiographic examination in the next few hours (days) and determination of the presence of reactive changes in the activity of a number of enzymes in the blood, body temperature ( see Myocardial infarction

).

Methods for diagnosing angina pectoris

An auxiliary method for diagnosing angina pectoris is the determination by analyzing laboratory parameters such as lipidogram, coagulogram, hemoglobin, glucose, and platelet levels.

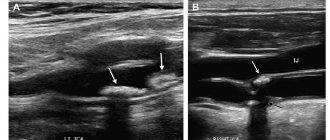

The most common instrumental methods confirming the diagnosis include: electrocardiography (ECG), echocardiography (EchoCG); stress ECG tests (Veloergometry or Treadmill test), daily (Holter) ECG monitoring (SM ECG), coronary angiography (CAG).

Treatment

Stopping an attack:

- calm, preferably sitting position of the patient;

- nitroglycerin under the tongue (1 tablet or 1 - 2 drops of a 1% solution on a piece of sugar, on a validol tablet), repeat taking the drug if there is no effect after 2 - 3 minutes;

- corvalol (valocardine) - 30 - 40 drops orally for sedative purposes;

- arterial hypertension during an attack does not require emergency medication, since a decrease in blood pressure occurs spontaneously in most patients;

- if nitroglycerin is poorly tolerated (bursting headache), then prescribe a mixture of 9 parts of 3% menthol alcohol and 1 part of a 1% nitroglycerin solution, 3 to 5 drops of sugar per dose.

The prognosis in the absence of complications is relatively favorable. The ability to work is preserved, but with a limitation of work that requires significant physical effort.

Do angina attacks mean an impending heart attack?

First of all, it is necessary to understand that an attack of angina is not a heart attack; it is the result of only a temporary lack of oxygen in the working heart muscle.

Unlike angina, with a heart attack, irreversible changes occur in the heart tissue due to the complete cessation of blood supply to this area. Chest pain during a heart attack is more severe, lasts longer and does not go away after rest or taking nitroglycerin under the tongue. During a heart attack, nausea, severe weakness and sweating are also observed.

It should be remembered that in cases where angina episodes become longer, occur more frequently and occur even during rest, the risk of developing a heart attack is quite high.

Can people with angina pectoris exercise?

Yes, definitely. However, when developing a schedule and intensity of physical activity, you should consult your doctor. Exercise will help you raise your pain threshold, reduce stress, improve oxygen supply to your heart and control your weight. Doctors advise gradually increasing physical activity, starting with small ones. You can start with a 5 minute daily walk and after a couple of months increase the time to 1/2 or 1 hour. Sudden overloads must be avoided.

What is the difference between stable and unstable angina?

It is necessary to distinguish the difference between stable angina (effort angina) and unstable angina (rest angina).

Angina attacks usually recur with predictable regularity. The patient can predict his condition by noting that attacks usually appear after stress or physical exertion. All this characterizes stable angina or exertional angina - the most common type of disease.

However, in some cases, angina can have an unpredictable course. This manifests itself in unexpectedly severe or frequently recurring attacks of chest pain that occur with minimal physical activity or even at rest. This form of angina is called unstable or resting angina and requires particularly careful treatment.

The term unstable angina is also used in the event of all the symptoms of a heart attack, which, however, are not confirmed by clinical tests and in which there is no damage to the heart muscle.