Development of hypertension

The essence of the disease is frequent and/or persistent increase in blood pressure.

The origin of the disease is still unknown, but there is disruption of the heart and increased vascular tone. Depending on the level of high blood pressure, there are three degrees of severity of hypertension: 1 degree (mild, soft) - the patient’s pressure is in the range from 140/90 to 159/99; 2nd degree (moderate) - pressure ranges from 160/100 to 179/109; Grade 3 (severe) - blood pressure above 180/110.

General information about the disease

The occurrence of complications due to high blood pressure is associated with damage to vital “target organs”: myocardium, brain, kidneys. The heart is the first to be involved in the pathological process. Already in the early stages of hypertensive disease, changes in the size of the organ, the shape of the cavities, and the thickness of the walls of the left ventricle are noted. Against the background of dystrophic transformations, the following is observed:

- the appearance of arrhythmia;

- development of ischemic disease;

- increase in heart failure;

- disturbance of atrioventricular conduction.

This form of hypertension is known to the general public as “hypertensive heart.”

A systematic increase in blood pressure threatens serious damage to the heart muscle, the development of such severe cardiovascular disorders as myocardial infarction, acute heart or kidney failure, and cerebral stroke.

Risk factors

A number of factors contribute to the development of hypertensive myocardial disease:

- geodynamic – cardiac output, vascular patency, elastic resistance, viscosity and volume of circulating blood;

- extracardiac – patient’s gender, age, excess weight, cholesterol level, diabetes mellitus, bad habits.

Dystrophic changes in the heart muscle are more common in young men suffering from arterial hypertension than in women. With age, the trend changes: the prevalence of pathology in females increases during menopause.

Obesity is a powerful factor that provokes cardiac hypertrophy. As body weight increases, the weight of the organ and the thickness of its walls also increase. Hereditary factors play a certain role.

Stages of hypertensive heart disease

Hypertension with primary damage to the heart goes through certain stages of development:

- The first stage is functional disorders: the oxygen demand of the heart muscle increases, the function of the left ventricle is impaired, the emptying index of the left atrium decreases, there are still no visible subjective symptoms.

- The second stage - the process of remodeling the myocardial structure begins, the left atrium enlarges.

- The third stage - the development of dystrophic changes continues, against the background of increased peripheral vascular resistance, left ventricular hypertrophy develops, when diagnosed, hypertensive heart disease without heart failure is determined.

- The fourth stage - heart failure develops as a consequence of the progression of hypertrophy and circulatory disorders.

As changes in the left ventricle increase, an imbalance arises between the high demand of the heart muscle for oxygen and the limited volumes of its supply through the coronary vessels.

As a result, hypertrophy goes from a physiological form to a pathological one.

The pathological process of heart damage in arterial hypertension goes through three stages of progression:

- initial – the occurrence of hypertension, the appearance of myocardial dysfunction;

- latent (compensatory) – stable balancing of impaired functions;

- impaired compensation – development of complications: heart attack, stroke, heart failure, death.

During this period, pronounced structural and vascular changes are observed:

- left atrium enlargement;

- thickening of the walls, expansion of the cavity of the left ventricle;

- growth of fibrous tissue;

- increasing collagen levels;

- accumulation of water in the walls;

- proliferation of vascular walls;

- impaired vascular response to the influence of vasoactive factors.

Pathological processes are accompanied by disruption of metabolic processes and microcirculation in the myocardium, as well as its contractile activity.

Symptoms of hypertension

In the absence of treatment and secondary prevention, the disease progresses. Depending on the damage to target organs, they are distinguished: Stage I. Typically, but not necessarily, characterized by a mild and intermittent increase in blood pressure without target organ damage. However, it is quite possible for both a crisis and a completely asymptomatic course of the disease. In addition to high blood pressure, the patient may be concerned about:

- headache;

- decreased performance;

- tendency to fluid retention;

- fast fatiguability.

Stage II is characterized by the appearance of signs of damage to target organs (heart, kidneys and brain, as well as blood vessels, including the eyes, which may be accompanied by the appearance of new symptoms and complaints, as well as according to additional laboratory and instrumental studies:

- pain in the “heart area”;

- dizziness;

- visual impairment;

- the appearance of edema;

- memory loss;

- shortness of breath on exertion.

Stage III - complicated hypertension. The main sign of the course of the disease at this stage is severe damage to target organs with thrombosis, including heart attacks and strokes, accompanied by the following symptoms:

- hand tremors;

- noise in the head or ears;

- significant memory loss;

- nausea, vomiting;

- persistent visual impairment;

- various heart disorders.

Most of these symptoms are stable and usually progress, reducing performance.

Symptoms

Headache is perhaps the most common manifestation of high blood pressure, or, as it is called, hypertension. It is associated with spasm of cerebral vessels. Sometimes other symptoms are observed: noise in the ears (such as a hum or ringing), flickering of “spots” or “sparkles” in the eyes, blurred vision. This is also due to impaired blood circulation in the areas of the brain responsible for sound and color perception, and in addition, the blood supply to the actual sound-receiving devices of the ear and the light-receiving structures of the eye is also disrupted. Shortness of breath may occur, as well as chest pain (this pain is associated with impaired blood supply to the heart muscle - the myocardium - due to the same vascular spasm).

Diagnosis of hypertension

Diagnosis of hypertension is performed by a cardiologist. To identify the disease and individualize treatment, the following methods are used:

- dynamic blood pressure measurement;

- laboratory tests - clinical and biochemical blood tests, general urine analysis;

- electrocardiography, including in the form of Holter monitoring;

- ultrasound examinations: heart, kidneys and other organs;

- Dopplerography (ultrasound of blood vessels).

Subjective symptoms of the disease

About 65% of patients suffering from cardiac hypertension report the following symptoms:

- shortness of breath, increased heart rate;

- headache, dizziness;

- hyperemia (redness) of the facial skin;

- moderate pressing pain in the chest;

- fluctuations in blood pressure;

- increased anxiety, feeling of fear.

The rest of the patients do not find any manifestations other than periodic or episodic increases in blood pressure. They lead their usual lifestyle until they encounter one of the possible complications of the pathology.

Treatment of hypertension

To treat the disease, both drug and non-drug therapy are used. Hypertension medications are aimed at preventing high blood pressure. The doctor also recommends lifestyle changes, such as a special diet or moderate exercise. In our clinics on Gorokhovaya St., 14/26

(metro station Admiralteyskaya, Admiralteysky district) and on

Varshavskaya st., 59

(metro station Moskovskaya, Moskovsky district) there are

therapists

and

cardiologists

who will diagnose and draw up a suitable treatment plan for hypertension.

You can make an appointment by calling 493-03-03 or on our website. Make an appointment

Predisposing factors

- excessive consumption of salt (more precisely, sodium, which is part of salt),

- atherosclerosis (these two diseases seem to reinforce each other and often go together),

- smoking,

- excessive drinking,

- increased body weight - obesity

- physical inactivity (that is, a sedentary lifestyle).

Treatment of hypertension involves the correction of all risk factors a person has. Sometimes this alone is enough to significantly reduce blood pressure.

treatment of hypertension When measuring blood pressure, doctors examine two parameters - the upper (systolic pressure) and the lower (diastolic). With some degree of convention, we can say that the main contribution to the first is the strength of heart contractions, and the second is supported by vascular tone. Therefore, when prescribing treatment, doctors are guided by which pressure - systolic or diastolic - is more elevated. In the first case, you need to “slow down” the heart a little, and in the second, you need to dilate the blood vessels.

Hypertension is dangerous because severe or constant vasospasm causes insufficient blood flow to vital organs - the heart, brain and kidneys. If there is excessive spasm of the arteries or if there are atherosclerotic plaques in the vessels, blood may completely stop flowing through the artery, and then a sharp circulatory disorder may occur. This is how stroke and myocardial infarction develop.

Treatment of arterial hypertension and coronary artery disease: two diseases - a single approach

Arterial hypertension and coronary heart disease within the cardiovascular continuum

Despite significant progress in clinical medicine, cardiovascular diseases (CVD) still dominate the structure of morbidity and mortality in developed countries [1,2]. In 1991, Dzau and Braunwald proposed the concept of the cardiovascular continuum, which is a chain of sequential events leading ultimately to the development of congestive heart failure and death of the patient. The trigger points of this “fatal cascade” are cardiovascular risk factors, arterial hypertension (AH), and diabetes mellitus [3].

Despite significant progress in clinical medicine, cardiovascular diseases (CVD) still dominate the structure of morbidity and mortality in developed countries [1,2]. In 1991, Dzau and Braunwald proposed the concept of the cardiovascular continuum, which is a chain of sequential events leading ultimately to the development of congestive heart failure and death of the patient. The trigger points of this “fatal cascade” are cardiovascular risk factors, arterial hypertension (AH), and diabetes mellitus [3].

Numerous studies prove the existence of a direct relationship between blood pressure (BP) levels and the risk of cardiovascular complications [4–7]. Also A.L. Myasnikov in 1965 in the monograph “Hypertension and Atherosclerosis” emphasized that “the combination of hypertension with atherosclerosis and associated coronary insufficiency is so common in practice and so predominates over “pure” forms that the task arises of considering these pathological conditions not only in their typical isolated form, but also in a frequently occurring complex.” A meta-analysis by MacMahon et al., based on the results of 9 prospective studies that included a total of more than 400,000 patients, once again confirmed that the likelihood of developing coronary heart disease (CHD) is in direct linear dependence on the level of both systolic blood pressure (SBP) and and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure [5]. In addition, hypertension is the most important prognostic factor for myocardial infarction.

(MI), acute and transient cerebrovascular accident, chronic heart failure, general and cardiovascular mortality [4–7]. In turn, the presence of coronary heart disease in a patient with hypertension, regardless of its form (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, previous myocardial revascularization surgery) can be considered as a “concomitant clinical condition” that significantly affects the patient’s overall cardiovascular risk. The International Society of Arterial Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology (ISH/ESC) recommend that a patient suffering from both hypertension and coronary artery disease be classified as a very high-risk group [8].

The relationship between hypertension and ischemic heart disease is quite understandable. Firstly, both diseases have the same risk factors (Table 1), and secondly, the mechanisms of occurrence and evolution of hypertension and coronary artery disease are largely similar. Thus, the role of endothelial dysfunction (ED) in the development of both hypertension and ischemic heart disease is generally accepted. An imbalance between the pressor and depressor systems for regulating vascular tone causes an increase in blood pressure at the initial stages, and subsequently stimulates remodeling processes of the cardiovascular system, affecting the left ventricle, main and regional vessels, as well as the microvasculature. At the level of the coronary arteries, ED stimulates atherogenesis, leading to the formation and ultimately destabilization of plaque, its rupture and the development of myocardial infarction (MI) [9,10]. Of particular interest is the fact that violations of the endothelium-dependent regulation of the tone of the coronary arteries create additional dynamic stenosis to the already existing anatomical one.

It is no less significant that left ventricular myocardial hypertrophy (LVH), an independent risk factor for cardiovascular complications, can be combined with myocardial ischemia even in the absence of coronary atherosclerosis. Experimental and clinical studies have shown that with LVH there is a decrease in the functional reserve of coronary blood flow, due to a number of mechanisms [11]:

– violation of autoregulation of coronary vessel tone;

– morphological changes in the vascular wall, an increase in the ratio of the thickness of the medial layer to the diameter of the lumen of the vessel;

– decrease in the density of capillaries and resistive arterioles in the myocardium;

– discrepancy between the rate of progression of LVH and the rate of neovascularization;

– an increase in LV filling pressure, contributing to the deterioration of myocardial perfusion, especially the endocardial layers;

– compression of the coronary vessels during systole against the background of an increase in the volume of blood supply to the myocardium as a result of LVH.

Thus, hypertension and coronary artery disease are diseases with the same risk factors, similar mechanisms of development and progression, which negatively affect the patient’s overall cardiovascular risk. Forming an idea of hypertension and coronary artery disease within a single cardiovascular continuum clearly demonstrates that the goal of treatment should not be individual diseases, but the patient as a whole.

General goals of treating a patient with arterial hypertension and coronary heart disease

Treatment of patients suffering from both coronary artery disease and hypertension requires an integrated approach, that is, simultaneous action on both conditions. The primary goal of treatment

is the maximum reduction in the overall risk of cardiovascular diseases and mortality by preventing myocardial infarction, cerebral stroke and chronic renal failure, and the reverse development of target organ damage [12–15]. Reduction of clinical manifestations and improvement of quality of life should be considered as second-line objectives. Speaking about coronary artery disease, first of all it is reducing the frequency and duration of angina attacks, as well as preventing its progression [14]. The goal of antihypertensive therapy itself is to achieve and stable maintenance of blood pressure at the target level (below 140/90 mmHg) [8,12,15].

Impact on risk factors

When developing a therapeutic strategy, we must not forget about the need for non-drug measures (Table 1). The latter involves taking such measures as stopping smoking, reducing excess body weight, maintaining regular physical activity, following a diet low in fat and sodium chloride (2–4 g), limiting alcohol consumption (no more than 20–30 g of ethanol per day for men and 10–20 g for women). Correction of risk factors can also include treatment of diabetes mellitus, taking lipid-lowering drugs in the presence of dyslipidemia [8,12,14,15].

Drug therapy of patients with arterial hypertension and angina pectoris

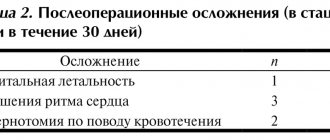

Most often, a practicing physician has to deal with situations where hypertension is combined with stable angina pectoris. The joint recommendations for the management of patients with stable angina of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (2002) suggest using the following as drug therapy, taking into account the level of evidence (Table 2) [14]:

- Class I

(treatment methods, the benefits and effectiveness of which have been proven and are beyond doubt among experts):– acetylsalicylic acid in the absence of contraindications (level of evidence A);

– b-blockers, as first-choice drugs in the absence of contraindications in patients who have had an MI (level of evidence A) and without a previous MI (level of evidence B);

– ACE inhibitors in all patients with coronary artery disease in combination with diabetes mellitus and/or left ventricular systolic dysfunction (evidence level A);

- lipid-lowering therapy in patients with established and suspected coronary artery disease and cholesterol levels more than 130 mg/dl with the goal of achieving low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels of less than 100 mg/dl (evidence level A);

– nitroglycerin sublingually or in the form of a spray to relieve an attack of angina (evidence level B);

– calcium antagonists or long-acting nitrates as first-choice drugs to reduce the symptoms of angina when b-blockers are contraindicated (evidence level B);

– calcium antagonists or long-acting nitrates in combination with b-blockers if the latter are insufficiently effective (level of evidence B);

– calcium antagonists or long-acting nitrates, as an alternative to b-blockers, if the latter lead to unwanted side effects (evidence level C).

- Class IIa

(treatment methods for which data on the benefits and effectiveness predominate):– clopidogrel if there are absolute contraindications to the use of acetylsalicylic acid (evidence level B);

– long-acting non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists as first-choice drugs instead of b-blockers (evidence level B);

– in patients with established and suspected coronary artery disease and cholesterol levels from 100 to 129 mg/dl, the following treatment approaches are possible (evidence level B):

– lifestyle changes or drug therapy to achieve LDL levels less than 100 mg/dL;

– reducing excess body weight or increasing physical activity in people suffering from metabolic syndrome;

– therapy of other (except dyslipidemia) conditions that are risk factors for the development of coronary artery disease; discussion of the use of niacin and fibrates for elevated triglycerides or decreased HDL;

– ACE inhibitors in patients with coronary artery disease and other vascular diseases (level of evidence B).

- Class IIb

(treatments with less clear preponderance of evidence of benefit and effectiveness):– warfarin in addition to acetylsalicylic acid (evidence level B).

- Class III

(treatment methods for which there is evidence and/or general agreement on ineffectiveness/inappropriateness and/or harm of use):– dipyridamole (level of evidence B).

b-blockers

β-blockers (BABs) are first-line drugs in the treatment of hypertension. The presence of tension angina in a patient with hypertension is an undeniable indication for prescribing a beta blocker. By reducing heart rate and blood pressure, drugs in this group increase the threshold physical activity that provokes an anginal attack. Under ideal conditions, the dose of beta blockers should be selected so that the heart rate does not exceed 75% of that during the load that provokes an angina attack. What determines the priority of choosing drugs from this group in patients suffering from hypertension in combination with coronary artery disease? Firstly, beta blockers significantly reduce cardiovascular mortality in patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease, increase survival after myocardial infarction, and reduce the risk of recurrent myocardial infarction, as well as stroke and heart failure in patients with hypertension [14–18]. Contraindications to their use are severe bradycardia, hypotension, severe conduction disturbances, sick sinus syndrome, severe congestive heart failure, bronchospastic diseases (even selective beta blockers in high doses can provoke bronchospasm), intermittent claudication, and hypersensitivity to drugs. BABs are often combined with nitrates to prevent reflex tachycardia while taking the latter. Combination therapy with nitrates and b-blockers is more effective than monotherapy with drugs from each group.

Nitrates

The antianginal effect of nitrates is primarily due to the development of peripheral vasodilation under the influence of released nitric oxide. As a result, blood flow to the heart decreases, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and myocardial oxygen demand decrease. In addition, nitrates also cause dilation of the coronary arteries directly. It is assumed that they increase the lumen of subepicardial arteries mainly at the site of eccentric stenoses, without having a significant effect on stenoses caused by concentrically located atherosclerotic plaques. The antiplatelet and antithrombotic effects of nitrates and the improvement of the rheological properties of blood have also been shown [19]. The various effects of nitrates cause an increase in exercise tolerance and, as a result, an improvement in the quality of life. Nitroglycerin in tablets for sublingual administration and in the form of a spray is used to relieve attacks of angina and prevent the development of episodes of myocardial ischemia before planned physical activity. To prevent anginal attacks, isosorbide di- or mononitrate is used orally or a transdermal patch with nitroglycerin. One of the disadvantages associated with long-term use of nitrates is the development of tolerance. When using short-acting nitrates, this undesirable effect can be overcome by creating a “nitrate-free” interval of several hours (called intermittent nitrate administration). However, it is preferable to use mononitrates in the form of special prolonged forms. One of these drugs is the retard form of isosorbide-5-mononitrate with gradual release of the active substance. 19 hours after its administration, the concentration of the active substance reaches a level below the minimum effective concentration (100 ng/ml). During this period of low nitrate content in the blood, sensitivity and vascular tone are restored, which prevents the development of tolerance [19]. Side effects of nitrates include headache, dizziness, tachycardia, and hypotension. Nitrates are contraindicated in idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and severe aortic stenosis.

Calcium antagonists

Calcium antagonists have a vasodilating effect, and the most powerful vasodilators are drugs from the dihydropyridine group. The mechanism of antianginal and hypotensive action is due to the ability to cause expansion of peripheral and coronary arteries. With less pronounced vasodilating properties, non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists have a distinct negative inotropic effect, suppress the activity of the sinus node and slow down atrioventricular conduction. This determines the feasibility of their use in persons suffering from stable angina and hypertension [20,21]. For variant angina, calcium antagonists are considered as the drugs of choice. Elderly patients with isolated systolic hypertension are a target group for the use of calcium antagonists, as long-acting dihydropyridines are able to prevent stroke in this population [20,21]. Phenylalkylamines and benzothiazepines are contraindicated in bradycardia, sinus node dysfunction, high-grade atrioventricular block and congestive heart failure.

ACE inhibitors

In SAVE

(the Survival And Ventricular Enlargement) and

SOLVD

(Studies Of Left Ventricular Dysfunction) revealed a decrease in the frequency of recurrent myocardial infarction during therapy with ACE inhibitors, which cannot be explained only by the hypotensive effect [22].

the HOPE

study confirmed that the use of ACE inhibitors reduces cardiovascular mortality, the risk of MI and stroke [23]. By influencing the level of plasminogen activator inhibitor-I, drugs in this group cause activation of fibrinolytic activity, which may be one of the reasons for reducing the risk of MI when taking these drugs. The beneficial effects of ACE inhibitors are due to their vasodilatory, antiplatelet, antiproliferative and antithrombotic properties [24]. These drugs are recommended to be prescribed in the presence of heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, after a MI and diabetic nephropathy. Pregnancy, hyperkalemia, bilateral renal artery stenosis are contraindications for their use.

Antiplatelet agents

Acetylsalicylic acid in small doses inhibits platelet aggregation and cell proliferation. Its anti-inflammatory properties may also play a clinical role, since inflammation is considered one of the causes of atherosclerotic plaque destabilization. Thus, acetylsalicylic acid is not only able to prevent the development of thrombosis, but also suppress atherogenesis. The use of acetylsalicylic acid leads to a reduction in overall mortality, the incidence of stroke, MI and other vascular complications [25]. The drug clopidogrel, which appeared in recent years, in one study demonstrated higher effectiveness compared to acetylsalicylic acid in terms of reducing the combined risk of myocardial infarction, cardiovascular mortality and ischemic stroke. However, at present, until new information is obtained, clopidogrel is indicated only if there are contraindications to the use of acetylsalicylic acid.

Lipid-lowering therapy

The need for the use of statins for secondary prevention of coronary artery disease is currently virtually beyond doubt. Additional evidence for their widespread use was provided by the ASCOTLLA

(Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial), which demonstrated the effectiveness of statins in preventing complications in people with hypertension and borderline or normal total cholesterol levels. Thus, in patients with hypertension, lipid-lowering therapy may be justified even with moderately elevated or borderline levels of total cholesterol and LDL [26].

Treatment of arterial hypertension during myocardial infarction

Hypertension is one of the main factors in the development of myocardial infarction. In addition, the rise in blood pressure may be due to activation of the sympathetic-adrenal system in the first hours of necrotic changes in the heart muscle. A hypertensive reaction adversely affects the course of myocardial infarction. An increase in afterload and left ventricular wall tension leads to an increase in myocardial oxygen demand and, consequently, to an expansion of the infarction zone and the development of complications. In the early period of acute large-focal MI, hypertension is one of the main risk factors for myocardial rupture [27].

In most cases, with effective pain relief and adequate therapy with nitrates and beta blockers, the use of additional antihypertensive drugs is not required. When MI is combined with uncontrolled hypertension, more active intervention is required. However, in this situation, it is important to remember that for effective thrombolysis, aggressive therapy until blood pressure normalizes is not required. On the first day, if the patient does not have a dissecting aortic aneurysm, it is recommended to reduce blood pressure by 15–20% [28]. This tactics of patient management is determined, on the one hand, by the need to reduce the risk of heart failure and arrhythmias, which often complicates MI with high blood pressure, and, on the other hand, by the fear of hypotensive reactions while taking thrombolytic drugs with a high probability of developing hemorrhagic stroke. The optimal treatment strategy is one that combines the effects on both conditions from the first minutes. Unfortunately, all practical recommendations developed to date do not fully meet these requirements. In patients with MI combined with hypertension and a high risk of complications, thrombolysis is a class IIb indication for SBP > 180 mmHg. and DBP >110 mm Hg. Intravenous nitroglycerin is contraindicated in patients with acute coronary syndrome and SBP <90 mmHg, as well as severe bradycardia (<50 beats/min).

Recommendations for the treatment of MI include stages that have become classic over the last decade:

– sublingual nitroglycerin followed by intravenous infusion, then in the form of a spray and/or orally to quickly eliminate pain and reduce high blood pressure (evidence level C);

– intravenous beta-blocker, if pain persists, subsequent oral administration in the absence of contraindications (level of evidence B);

– with contraindications to beta blockers: non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists (level of evidence B);

- if the antihypertensive effect of nitroglycerin and/or beta blockers is insufficient (with concomitant LV dysfunction and heart failure) and/or non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists, ACE inhibitors are prescribed (level of evidence B);

– first choice drugs for patients with variant angina (with a normal coronary angiogram or with non-obstructive lesions of the coronary arteries) are nitrates and calcium antagonists;

– the administration of short-acting dihydropyridines to patients with unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction is contraindicated.

In recent years, data from multicenter controlled studies have allowed these recommendations to be revised and modified. In particular, early use of beta blockers is indicated not only regardless of thrombolysis, but also of primary angioplasty. The effectiveness of early administration of beta blockers has also been established for non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Relative indications (class II) for the use of beta blockers in the post-infarction period are supplemented by a history of non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. The use of beta blockers for moderate and severe left ventricular dysfunction in the post-infarction period has moved from absolute contraindications to relative indications. The lower limit of SBP is indicated as 100 mmHg. Art. for the use of ACE inhibitors on the first day of MI [29].

The management of patients with hypertension in the post-infarction period includes the mandatory prescription of beta blockers, ACE inhibitors and retard forms of nitrates. Calcium antagonists are used as reserve drugs for intolerance to beta blockers. Patients after myocardial infarction are not recommended to prescribe thiazide diuretics as monotherapy if rhythm disturbances are detected on the ECG: due to the possibility of developing life-threatening arrhythmias [15].

Arterial hypertension and acute coronary syndrome

The strategy for providing care to patients with acute coronary syndrome without ST elevation is determined by the risk of developing acute myocardial infarction. This risk is higher the less time has passed since the first signs of exacerbation of coronary artery disease and the greater the severity of the anginal attack and ECG changes (ST depression and T-wave inversion). Patients with unstable angina should be hospitalized immediately. From the moment the patient is hospitalized, treatment should begin aimed at preventing the increase in coronary thrombosis and the development of necrotic changes in the myocardium:

– administration of acetylsalicylic acid orally 250–500 mg (first dose – chew the tablet) then 125–250 mg per day for a single dose;

– administration of unfractionated heparin (intravenous bolus 60–80 units/kg, but not more than 5000 units), then intravenous infusion (12–18 units/kg/h, but not more than 1250 units/kg/h with aPTT determination every 6 hours) for 1–2 days, or administration of low molecular weight heparins at a dose of 1 mg/kg every 12 hours subcutaneously for 2–5 days;

– prescription of antianginal drugs from the groups of beta blockers and nitrates. [thirty]

In high-risk groups, beta blockers are prescribed intravenously, then orally. Calcium antagonists are used as second-line drugs in addition to nitrates and beta blockers (with the exception of variant angina). Monotherapy with short-acting dihydropyridines is absolutely contraindicated due to the worsening prognosis in such patients. Non-digropyridine calcium antagonists are used either when the use of beta blockers is contraindicated, when left ventricular function is normal, or in addition to beta blockers when they are absent or insufficiently effective. It should be remembered that the combined use of these drugs can lead to a marked decrease in the ejection fraction of the left ventricle, so the prescription of a combination of beta blockers and non-digropyridine calcium antagonists should be short-term. ACE inhibitors can be used in all patients with acute coronary syndrome, always with concomitant hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction. For variant angina, nitrates and calcium antagonists are highly effective, and preference should be given to the group of long-acting nitrates [31].

Thus, currently, practicing physicians have a wide arsenal of medications for the treatment of patients with coronary artery disease and hypertension.

It is a generally accepted fact that it is necessary to combat the risk factors of hypertension and coronary artery disease, as well as the use of a whole range of non-drug treatment methods. This comprehensive approach allows us to improve the prognosis and improve the quality of life. Literature:

1. Makolkin V.I., Podzolkov V.I. Hypertonic disease. M.; 2000. – 96 p.

2. Kobalava Zh.D., Kotovskaya Yu.V. Arterial hypertension 2000. M.; 2000. – 208 p.

3. Dzau V., Braunwald E. Resolved and unresolved issues in the prevention and treatment of coronary artery disease: a workshop consensus statement. Am. Heart J 1991; 121(4 Pt 1):1244–1263.

4. Stamler J., Neaton J., Wentworth D. Blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) and risk of fatal coronary heart disease. Hypertension 1993; 13:2–12.

5. MacMahon S., Peto R., Cutler J., et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 1990; 335:765–774.

6. Kannel WB Fifty years of Framingham Study contributions to understanding hypertension. J.Hum. Hypertens. 2000; 14:83–90.

7. Kannel WB Risk stratification in hypertension: new insights from the Framingham Study. Am. J. Hypertens. 2000; 13 (1 Pt 2):3S–10S.

8. Guidelines Subcommittee. 2003 European Society of Hypertension – European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2003; 21:1011–1053.

9. Celermajer DS Endothelial dysfunction: does it matter? Is it reversible? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1997; 30:325–333.

10. Vita JA, Treasure CB, Nabel EG et al. Coronary vasomotor responses to acetylcholine relate to risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circulation 1990; 81:491–497.

11. Isoyama S. Coronary vasculature in hypertrophy. In: Sheridan DJ, ed. Left Ventricular Hypertrophy, 1st ed. London.; 1998:29–36.

12. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation and treatment of high pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289:2560–2572.

13. Syrkin A.L. Treatment of stable angina. Consilium medicum. 2000; 2:470–477.

14. ACC/AHA 2002 Guideline Update for the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina Angina).

15. First Report of experts from the scientific society for the study of Arterial Hypertension, the All-Russian Scientific Society of Cardiologists and the Interdepartmental Council on Cardiovascular Diseases. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of primary arterial hypertension in the Russian Federation. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapy 2000; 9 (3):5–30.

16. Aronov D.M. The role of beta-blockers in the treatment of stable angina. RMJ 2000; 8:71–77

17. Podzolkov V.I., Samoilenko V.V., Osadchiy K.K., Strizhakov L.A. The use of metoprolol CR/ZOK in cardiological practice. Ter. archive. 2000; 9:78–80.

18. Psaty BM, Smith NL, Siscovick DS, et al. Health outcomes associated with antihypertensive therapies used as first–line agents: a systematic review and meta–analysis. JAMA 1997; 277:739–745.

19. Lupanov V.P. Stable angina: tactics of treatment and management of patients in hospital and outpatient settings. RMJ 2003; 11:65–70

20. Martsevich S.Yu. The role of calcium antagonists in the modern treatment of cardiovascular diseases. RMJ 2003; 11:539–541

21. Makolkin V.I. Calcium antagonists in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. RMJ 2003;11:511–513.

22. Lonn EM, Yusuf S, Jha P, et al. Emerging role of angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitors in cardiac and vascular protection. Circulation 1994; 90:2056–69.

23. Yusulf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, rarnipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N.Engl. J. Med. 2000; 342:145–53.

24. Makolkin V.I. Arterial hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. RMJ 2002; 10:862–865.

25. The role of aspirin in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases: new data. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapy 2003; 12:11–14.

26. Statins and arterial hypertension. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapy 2003; 12:8–11.

27. Myocardial Infarction Redefined – A Consensus Document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee. Eur. Heart. J. 2000; 21:1502–1513.

28. Ruksin V.V. Emergency cardiology. St. Petersburg; 1999. – 471 p.

29. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina and Non–ST–Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000; 36:970–1062.

30. Management of acute coronary syndromes: acute coronary syndromes without persistent ST segment elevation. Recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2000; 21:1406–32.

31. Treatment of acute coronary syndromes without ST segment elevation. Russian recommendations. Developed by the Expert Committee of the All-Russian Scientific Society of Cardiology. Consilium Medicum 2001; 3 (Supplement):4–15.

Advantages of diagnosing and treating hypertension at the Miracle Doctor clinic:

- Doctors. The therapists at our clinic have extensive experience in treating various forms of hypertension. Doctors of other specialties actively help them in this: cardiologists, neurologists, ophthalmologists.

- Instrumental diagnostics. Hypertension may be episodic and therefore go undetected with routine blood pressure measurements. For more detailed diagnostics, our clinic conducts 24-hour blood pressure monitoring using a special portable device fixed on the patient’s body. In this case, the patient can stay at home and do his usual work.

- Laboratory equipment. Hypertension often occurs against the background of changes in hormonal levels, blood glucose levels and urine properties. The laboratories of our clinic, equipped with modern equipment, determine all the necessary indicators in blood and urine tests.