In case of ventricular tachycardia, the patient should be immediately provided with competent assistance to avoid death. The sequence of actions is described below, as well as the necessary medications that will make a person feel better.

- Tachycardia with wide QRS complex

- Treatment

- WPW and PQ phenomena

- Risk of atrial fibrillation and flutter

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) before connecting the ECG monitor.

- If ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia (VF/VT) is present, the monitor shows three consecutive defibrillator shocks with gradually increasing strength.

- If VF/VT persists or recurs, continue CPR, tracheal intubation, and access to the vein.

- Adrenaline 1 mg every 3-5 minutes.

- Repeated defibrillator shocks.

- Cordarone 5 mg/kg intravenously (or lidocaine 1.5 mg/kg) for 3-5 minutes if there is no effect after the 3rd discharge of the defibrillator.

Tachycardia with wide QRS complex

In case of paroxysm with a wide QRS complex (more than 0.12 s) and the impossibility of recording a transesophageal ECG, the following cannot be excluded:

• paroxysm of supraventricular tachycardia with blockade of the legs of the atrioventricular bundle (permanent or transient, frequency-dependent);

• paroxysm of supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation and flutter with impulse conduction along additional pathways.

In doubtful cases, wide complex tachycardia should be regarded as ventricular.

Diagnostic measures

- Taking anamnesis (simultaneously with diagnostic and therapeutic measures);

- Examination by an emergency medical technician (paramedic) or a medical specialist from a visiting emergency medical team of the appropriate profile;

- Registration of an electrocardiogram, decoding, description and interpretation of electrocardiographic data;

- Monitoring of electrocardiographic data;

- Pulse oximetry;

- General thermometry.

For unstable hemodynamics:

- Diuresis control;

For anesthesiologists and resuscitators:

- Control of central venous pressure (in the presence of central venous access).

Treatment

Treatment should begin with a trial administration of lidocaine 1 mg/kg (80-120 mg) in 20 ml of isotonic sodium chloride solution for 4-5 minutes, repeat the administration after 5-10 minutes at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg until dose 3 is reached mg/kg. The effect of lidocaine administration usually favors a ventricular origin of the tachycardia.

If there is no effect, and also taking into account the possible supraventricular nature of the tachycardia, it is recommended to administer ATP - 10 mg intravenously in a bolus with repeated administration of 10-20 mg. If tachycardia is not stopped, it is necessary to administer either procainamide 10% - 10 ml in 10 ml of isotonic sodium chloride solution, or amiodarone 5 mg/kg intravenously in a 5% glucose solution over 10 minutes.

You can begin stopping broad complex tachycardia with parenteral administration of procainamide or amiodarone (the latter is indicated in patients with severe structural changes in the myocardium and heart failure).

If paroxysmal tachycardia is accompanied by hemodynamic disturbances or there is no effect from drug therapy, electrical cardioversion is necessary.

After successful relief of tachycardia with a wide QRS complex of unknown etiology, the patient should be hospitalized to clarify the diagnosis and choose further treatment tactics.

The syndrome of premature excitation of the ventricles, or preexcitation syndrome, is that part of the myocardium along the accessory pathways (APP) is excited earlier than when the impulse is carried out through a normally functioning conduction system.

Some patients with DPP do not have paroxysmal rhythm disturbances, which is due to the peculiarities of the electrophysiological properties of these pathways, as well as a favorable ratio of indicators characterizing the conductivity and refractoriness of normal and additional pathways.

Relief and prevention of paroxysmal cardiac arrhythmias

P

Aroxysmal heart rhythm disturbances are one of the common manifestations of cardiovascular diseases. Arrhythmias such as ventricular and supraventricular tachycardia, paroxysms of atrial fibrillation and flutter can cause severe hemodynamic disorders, lead to the development of pulmonary edema, arrhythmogenic shock, acute coronary insufficiency, etc. Some types of arrhythmias, in particular ventricular tachycardia, especially polymorphic, “pirouette”, atrial fibrillation in WPW syndrome, can transform into flutter and ventricular fibrillation and cause sudden cessation of blood circulation. Therefore, patients with dangerous types of arrhythmias often require assistance aimed at emergency relief and prevention of paroxysms. At the same time, it is known that serious complications are possible during antiarrhythmic therapy. Therefore, the issues of treatment and prevention of paroxysmal arrhythmias are very relevant, but their solution often causes difficulties for doctors. The data available in the literature regarding the tactics of emergency treatment of paroxysmal arrhythmias [1–7] are not without contradictions.

To successfully stop paroxysmal arrhythmias, accurate identification of their types according to ECG data is necessary. The main types of these arrhythmias, divided according to the principle of differentiated treatment tactics, and their ECG signs are presented in Table 1.

Express diagnosis of paroxysmal arrhythmias can be difficult. In particular, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia or atrial flutter with aberrant ventricular complexes may be difficult to distinguish from ventricular tachycardia. In some cases, accurate diagnosis is possible only by recording the esophageal lead of the ECG, which makes it possible to identify P waves or F waves that do not differ in standard leads.

When determining the tactics and methods of treating arrhythmias, it is important to take into account what disease the patient suffers from and what factors contribute to the occurrence and relief of arrhythmia. For example, in patients with coronary heart disease, to relieve paroxysms accompanied by signs of myocardial ischemia, the use of verapamil or propranolol, which have an antianginal effect, is more justified; if there are signs of heart failure, it is advisable to use amiodarone or digoxin; for arrhythmias that have developed against the background of electrolyte imbalance, treatment should include magnesium supplements. Among the antiarrhythmics used to normalize the rhythm in case of electrolyte imbalance, the use of the drug Magnerot

, containing 500 mg of magnesium orotate. Magnesium orotate does not exacerbate intracellular acidosis (unlike drugs containing magnesium lactate), which often occurs in patients with heart failure. In addition, orotic acid, which is part of Magnerot, is involved in the metabolic process in the myocardium and fixes magnesium on ATP in the cell, which is necessary for the manifestation of its action. The drug is prescribed 2 t. 3 times a day for 7 days, then 1 t. 2-3 times a day. The duration of treatment is 4–6 weeks.

When choosing an antiarrhythmic drug, it may be important to take into account the results of previous therapy, as well as the patient’s subjective attitude towards the prescribed treatment. Assessing all these data plays an important role in selecting effective therapy and reducing the risk of side effects. The last circumstance is especially significant, because Antiarrhythmic therapy can lead to more severe consequences than the arrhythmia itself. According to our data [2], during emergency drug antiarrhythmic therapy, serious, life-threatening complications are observed in 3.5% of cases

. In this regard, the feasibility of attempts to quickly stop arrhythmia with intravenous administration of antiarrhythmics at the prehospital stage should be carefully weighed. In our opinion, such attempts are permissible in two situations: 1 – if the hemodynamics are stable, the paroxysm is subjectively poorly tolerated, the probability of restoring the normal rhythm is high and, if successful, hospitalization will not be required; 2 – if there are severe hemodynamic disorders or there is a high probability of developing ventricular fibrillation (asystole) and transporting the patient in this condition poses a high risk. In the latter option, which is quite rare, the use of electric pulse therapy (EPT) is permissible. Much more often, the patient’s condition allows him to be hospitalized, taking into account the fact that antiarrhythmic therapy in a hospital setting is less risky.

Taking into account all these factors, when determining treatment tactics, it is necessary to keep in mind that one of the main ones is the nature of the arrhythmia.

Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia

This collective term summarizes the various types of atrial and atrioventricular tachycardia. The most common of them are atrioventricular reciprocal tachycardia, orthodromic tachycardia with latent or overt WPW syndrome and atrial reciprocal tachycardia (Table 1). These arrhythmias have differences in management tactics.

For atrioventricular reciprocal and orthodromic tachycardia

associated with latent ventricular pre-excitation syndrome, relief should begin with mechanical methods of irritation of the vagus nerve, among which the most effective are straining at the height of a deep breath and massage of the carotid sinus. You should not apply pressure on the eyeballs recommended by a number of authors due to the risk of eye damage, the pain of this manipulation and lower effectiveness compared to the above tests. If there is no effect from these mechanical techniques, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) should be administered intravenously in a rapid stream at a dose of 20 mg, unless there are indications of sick sinus syndrome (SSNS) and typical WPW syndrome. This drug is preferred due to the relatively low risk of side effects. If there is no effect in the case of stable hemodynamics, you can resort to intravenous administration of verapamil at a dose of 10 mg in a rapid stream. Procainamide, ajmaline or amiodarone can be used as alternative drugs. It is possible to use other drugs, in particular, propranolol, propafenone, disopyramide, which, depending on the situation, can be used not only intravenously, but also orally. If there is no effect, EIT is indicated. The latter is the drug of choice for atrioventricular tachycardia with severe hemodynamic disturbances (arrhythmogenic shock, pulmonary edema, cerebral dyscirculation).

In case of moderately severe hemodynamic disorders (so-called unstable hemodynamics), if vagal tests and ATP are ineffective, amiodarone or digoxin can be administered intravenously, and after improvement, if the rhythm has not been restored, resort to planned oral therapy or EIT.

In patients with severe forms of SSSS

(brady- and tachycardia syndrome, attacks of asystole) the means of choice for stopping tachycardia paroxysms is electrical cardiac pacing (ECS); it is also possible to carry out EIT in an intensive care unit.

In patients with typical WPW syndrome

when stopping attacks of tachycardia (including those with narrow QRS complexes), verapamil, ATP and cardiac glycosides should not be used due to the risk of developing antidromic tachycardia with wide QRS complexes and a high rhythm frequency with a possible transition to ventricular flutter. In such cases, vagal tests, procainamide or amiodarone intravenously can be used; ajmaline and propafenone can also be effective. For antidromic tachycardia with wide ventricular complexes, the same drugs and EIT are effective (vagal tests are not advisable).

A generalized algorithm for stopping paroxysms of atrioventricular tachycardia is presented in Figure 1.

Rice. 1. Algorithm for stopping paroxysms of supraventricular tachycardia

For paroxysms of atrial reciprocal tachycardia, verapamil, beta-blockers, amiodarone or digoxin, as well as EIT can be used to stop attacks and slow down the heart rate. Automatic and chaotic atrial tachycardia more often require not emergency, but planned therapy.

Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

This term refers to atrial fibrillation that has lasted no more than 7 days with the possibility of spontaneous relief. Attacks of atrial fibrillation, especially normo- and bradysystolic forms, often do not cause pronounced hemodynamic disorders and may not be accompanied by a noticeable deterioration in the patient’s condition and well-being. Under these circumstances, emergency antiarrhythmic therapy is not required, because it may worsen the patient's condition. However, attempts to restore normal rhythm are advisable, and this is best done with the help of antiarrhythmic drugs prescribed orally. Among the latter, first of all, we can name propafenone in a dose of 450–600 mg once and quinidine 200 mg every 4 hours in a total dose of up to 1.2 g. Propranolol (20 mg per dose), Magnerot

(1000 mg 3 times a day).

In patients with severe organic heart pathology, with clinical signs of heart failure or arterial hypotension, quinidine, propafenone and propranolol are not indicated. In such cases, you can use amiodarone at a dose of 1.2–1.8 g per day or digoxin in combination with potassium and magnesium preparations ( Magnerot

). In case of a poorly subjectively tolerated tachysystolic form of arrhythmia with stable hemodynamics, it may be advisable to try to restore sinus rhythm with the help of intravenous administration of antiarrhythmics. In our country, novocainamide is most often used for this purpose in a dose of up to 1.0 g, administered over 10–20 minutes. Ajmaline, which is administered intravenously over 10–15 minutes at a dose of up to 100 mg, is more effective. In the foreign literature, there are indications of the high reversing effectiveness of the IC class drug flecainide, as well as class III drugs dofetilide and ibutilide [8]. A representative of the latter class is the domestic drug nibentan, the stopping effectiveness of which for this arrhythmia is about 80% [9]. During attacks accompanied by critical hemodynamic disturbances, as well as during paroxysms with pronounced tachycardia and wide QRS complexes in patients with WPW syndrome, emergency EIT is indicated, but such cases are rare. For less severe hemodynamic disturbances, amiodarone can be used intravenously in a stream and drip at a dose of up to 1.5 g per day or digoxin, followed (if necessary) by planned antiarrhythmic therapy or EIT.

There are a number of conditions in which attempts to urgently relieve paroxysms of atrial fibrillation are not indicated. Such conditions include severe forms of SSSU, a high risk of thromboembolism, severe chronic hemodynamic disorders, attacks of arrhythmia lasting more than two days, and some others. In such cases, treatment should be aimed at stabilizing hemodynamics, slowing the heart rate and preventing thromboembolism.

The algorithm for anti-atyrmic therapy for paroxysms of tachysystolic atrial fibrillation is presented in Figure 2.

Rice. 2. Algorithm for the treatment of paroxysms of atrial fibrillation (with ventricular tachysystole)

For paroxysms of atrial fibrillation with ventricular bradysystole, antiarrhythmic therapy is usually not indicated.

For persistent and constant forms of atrial fibrillation

Emergency care may be required only in cases of a sharp increase in the ventricular rhythm and is aimed at slowing down the latter, improving the condition and well-being of the patient. This is usually achieved by intravenous verapamil or digoxin.

When treating atrial fibrillation, along with antiarrhythmic drugs, antithrombotic drugs should be prescribed, which are an important part of the planned therapy of such patients.

Paroxysmal atrial flutter

Atrial flutter. being one of the forms of atrial fibrillation, its clinical manifestations differ little from atrial fibrillation, but it is characterized by slightly greater persistence of paroxysms and greater resistance to antiarrhythmic drugs. There are regular (rhythmic)

and

the irregular form

of this arrhythmia.

The latter is clinically more similar to atrial fibrillation. In addition, there are two main types of atrial flutter:

1 – classic (typical); 2 – very fast (atypical). Their distinctive features are presented in Table 1.

The treatment tactics for paroxysms of atrial flutter largely depend on the severity of hemodynamic disorders and the patient’s well-being. This arrhythmia, even with significant ventricular tachysystole, often does not cause severe hemodynamic disturbances and is little felt by the patient. In addition, such paroxysms are usually difficult to stop with intravenous administration of antiarrhythmics, which can even cause a deterioration in the patient’s condition. Therefore, in such cases, emergency therapy is usually not required. If arrhythmia is poorly tolerated, verapamil or propranolol can be administered intravenously, and in the presence of hemodynamic disorders, digoxin can be administered, which will slow down the ventricular rhythm and improve the patient’s condition. Thus, attacks of atrial flutter should often be stopped not urgently, but routinely. The exception is rare cases when attacks of this arrhythmia cause critical hemodynamic disorders. In such situations, emergency EIT is indicated.

Speaking about drug treatment of this arrhythmia, it should be borne in mind that, according to the authors of the “Sicilian Gambit” concept, paroxysms of type 1 atrial flutter are better treated with class IA drugs (quinidine, procainamide, disopyramide), however, when using drugs of this class there is there is a risk of paradoxical acceleration of the ventricular rate, so it is better to first use verapamil or beta-blockers. Paroxysms of type 2 atrial flutter are better controlled by class III drugs, in particular amiodarone. Domestic authors [9] noted the high effectiveness of nibentan in relieving atrial flutter.

Drug-refractory atrial flutter is treated with frequent atrial pacing via an esophageal lead or EIT.

Paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia

This term denotes rhythms emanating from ectopic foci located distal to the bifurcation of the His bundle with an impulse frequency of 130–250 per minute, as well as bursts of ventricular extrasystoles of more than 5 in a row. Episodes lasting more than 30 seconds are called sustained, and less - non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. In addition, depending on the constancy or variability of the shape of the ventricular complexes, mono- and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia are distinguished. Short-term episodes of ventricular tachycardia may be asymptomatic; persistent tachycardia, as a rule, causes hemodynamic disturbances. It is known that in patients with organic heart diseases, especially with decreased contractility of the left ventricle, ventricular tachycardia can be an independent factor that aggravates the life prognosis. Some types of paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia, especially polymorphic (“pirouette”), can directly transform into ventricular flutter and fibrillation, causing circulatory arrest and sudden arrhythmic death. Therefore, paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia almost always requires special therapy aimed at eliminating and preventing attacks.

The tactics for emergency relief of paroxysms of ventricular tachycardia largely depend on the severity of hemodynamic disorders

. In the presence of severe hemodynamic disorders (their options are indicated above), emergency EIT is indicated. With moderate signs of unstable hemodynamics, preference should be given to intravenous administration of amiodarone at a dose of 150 mg over 10 minutes, then 300 mg over 2 hours, followed by a slow infusion of up to 1800 mg per day. An alternative is to inject lidocaine at a dose of up to 200 mg over 5 minutes. If there is no effect and worsening hemodynamic disorders, EIT is indicated. With stable hemodynamics, it is better to start relief with the administration of lidocaine at the dose indicated above, and if there is no effect, use procainamide in a dose of up to 1.0 g for 10–20 minutes. When systolic blood pressure decreases below 100 mm, this drug can be combined with mezaton. In addition to procainamide, you can use mexiletine in a dose of up to 250 mg or ajmaline up to 100 mg intravenously over 10–20 minutes, as well as amiodarone in the dose indicated above. If there is no effect, EIT is indicated. The algorithm for stopping paroxysms of ventricular tachycardia is presented in Figure 3.

Rice. 3. Algorithm for stopping paroxysms of ventricular tachycardia

To relieve paroxysms of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia of the “pirouette” type, lidocaine or magnesium sulfate intravenously, as well as EIT, can be used.

In the presence of long QT interval syndrome, you should not use drugs that slow down ventricular repolarization, in particular, amiodarone, procainamide, ajmaline, etc., although in case of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia without prolongation of the QT interval, the use of these drugs is acceptable. There are congenital and acquired prolongation of the QT interval. Congenital long QT interval syndrome

is a combination of an increase in the duration of the QT interval on a regular ECG with paroxysms of ventricular tachycardia “pirouette”, clinically manifested by syncope and often ending in “sudden death” in children and adolescents.

Acquired prolongation of the QT interval

can occur with atherosclerotic or post-infarction cardiosclerosis, with cardiomyopathy, against the background and after suffering myo- or pericarditis.

An increase in QT interval dispersion (more than 47 ms) may also be a predictor of the development of arrhythmogenic syncope in patients with aortic heart defects. Patients with congenital prolongation of the QT interval require constant use of b-blockers in combination with Magnerot

(2 tablets 3 times a day).

To stop the acquired prolonged QT interval, intravenous administration of Cormagnesin-400

at the rate of 0.5–0.6 g of magnesium per 1 hour during the first 1–3 days, followed by a transition to daily oral administration

of Magnerot

2 tablets. 3 times for at least 4–12 weeks. There is evidence that in patients with acute myocardial infarction who received such therapy, normalization of the value and dispersion of the QT interval and the frequency of ventricular arrhythmias were noted.

Recently, a study was conducted on 26 schoolchildren with prolongation of the QT interval (QTshould = 0.329 ± 0.005 s, QTis = 0.362 ± 0.006 s) and mitral valve prolapse, who received propranolol 10 mg twice a day and magnesium supplements at the rate of 200 mg per day . In this group of patients, a significant increase in QT on the ECG - by 9.1% after treatment (before treatment - 0.329±0.005 sec, after treatment - 0.359±0.005, p<0.01) is due to the total negative chronotropic effect of b-blockers and magnesium: Heart rate before treatment was 84.3±4.5 per 1 min, after treatment – 70.9±2.6 per 1 min (p<0.001).

The effect of magnesium drugs that normalizes the duration of the QT interval neutralizes the possible prolongation of the QT interval on the ECG under the influence of b-blockers (due to slowing of the rhythm), which is documented by the absence of a statistically significant difference after treatment between QTmeas and QTshould (QTmeas – 0.363±0.007 s, QTmust – 0.359 ±0.005 s, p>0.05).

Prevention of paroxysmal arrhythmias

For paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation and flutter, supraventricular tachycardia), it is advisable to prescribe preventive therapy mainly in the presence of frequent (occurring several times a month) attacks

. The exception is patients with malignant, severe or life-threatening paroxysms, when such treatment is also necessary for more rare attacks. Usually, with rare paroxysms, it is more profitable for the patient to stop them with one-time doses of antiarrhythmics than to take the latter for a long time for prevention. The same tactics are recommended for rare attacks of benign ventricular tachycardia.

For the prevention of paroxysms of supraventricular arrhythmias, amiodarone, sotalol and propafenone are most effective; etacizin, allapinin and disopyramide may also be effective. The last four drugs belonging to class IC should be prescribed only to patients with mild organic heart pathology, in the absence of a decrease in myocardial contractility. In the presence of pronounced changes in the myocardium and decreased contractility of the left ventricle, the use of amiodarone is preferable; it is possible to prescribe beta-blockers (atenolol, metoprolol, etc.), starting with small doses.

Considering the possibility of developing side effects and addiction to antiarrhythmic drugs with long-term continuous use, we recommend carrying out preventive therapy in the form of intermittent courses, stopping treatment when the effect is achieved and resuming it as necessary.

For malignant types of ventricular tachycardia, preventive therapy is necessary regardless of the frequency of attacks, and it must be carried out continuously. However, to reduce the likelihood of side effects and addiction, it is possible to alternate between effective antiarrhythmics, for example, amiodarone and sotalol. According to randomized studies [10,11], the latter two drugs are most effective in preventing life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.

, the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators has increasingly entered clinical practice.

to reduce the risk of death in patients with malignant ventricular arrhythmias [12]. The possibilities of combined use of these devices and medicinal antiarrhythmic drugs are being studied.

In conclusion, it must be emphasized that the goal of antiarrhythmic therapy is not only the elimination and prevention of paroxysmal arrhythmias, but also the improvement of life prognosis, and for this it is very important to prevent the negative hemodynamic and proarrhythmic effects of the prescribed drugs.

Literature:

1. Doshchitsin V.L. Treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. M., “Medicine”, 1993. – 320 p.

2. Doshchitsin V.L., Chernova E.V. Emergency care for patients with cardiac arrhythmias. Russian Journal of Cardiology, 1996, No. 6, pp. 13–17

3. Kushakovsky M.S. Cardiac arrhythmias (2nd edition). St. Petersburg, “Foliant”, 1998.–640 p.

4. Ardashev V.N., Steklov V.I. Treatment of heart rhythm disorders. M., 1998., 165 p.

5. Fomina I.G. Cardiac RI disorders, 2003. – 192 p.

6. Bunin Yu.A. Treatment of cardiac tachyarrhythmias. M. 2003.– 114 p.

7. Prokhorovich E.A., Talibov O.B., Topolyansky A.V. Treatment of rhythm and conduction disorders at the prehospital stage. Attending physician, 2002, No. 3, p. 56–60

8. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for management of patients with atrial fibrillation. European Heart J., 2001, 22, 1852–1923

9. Ruda M.Ya., Merkulova I.N., Dragnev A.G. and others. Clinical study of a new antiarrhythmic drug of the III class, nibentan. Message 2: effectiveness in patients with supraventricular rhythm disturbances. Cardiology, 1996, No. 6, pp. 28–37

10. The CASCADE Investigators. Randomized antiarrhythmic drug therapy in survivors of cardiac arrest. Amer. J. Cardiol., 1993, 72, 280–287

11. Mason JW, for the Electrophysiologic Study vs Electrocardiographic Monitoring (ESVEM) Investigators. A comparison of electrophysiologic testing with Holter monitoring to predict antiarrhythmic drug efficacy for ventricular tachyarrhythmias. N.Engl.J.Med., 1993, 329,445–451

12. Siebels J., Kuck K. and the CASH Investigators. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator compared with antiarrhythmic drug therapy in cardiac arrest survivors. Amer. Heart J., 1994, 127, 1139–1144

WPW and PQ phenomena

In such cases we are talking about the WPW phenomenon (Kent's beam) or the phenomenon of the shortened PQ interval (James' beam).

Main ECG criteria for the WPW phenomenon:

- shortening of the R-L interval (less than 0.12 s);

- the presence of a delta wave at the initial rise of the QRS complex;

- widening of the QRS complex due to the presence of a delta wave;

- change in the final part of the ventricular complex.

It should be noted that the physician’s ignorance of the ECG signs of the WPW phenomenon is the reason for the incorrect interpretation of these changes as signs:

- acute myocardial infarction,

- hypertrophy of both ventricles

- or blockade of the legs of the atrioventricular bundle.

The WPW phenomenon, as a rule, does not require treatment.

ECG signs of preexcitation syndrome against the background of sinus rhythm vary widely, which is associated with the degree of preexcitation and the constancy of conduction along the AP. The following options are possible:

1) the ECG constantly shows signs of pre-excitation (manifest pre-excitation syndrome);

2) on the ECG, signs of preexcitation are transient (intermittent or transient preexcitation syndrome);

3) The ECG is normal under normal conditions, signs of pre-excitation appear only during the period of paroxysm (latent pre-excitation syndrome).

The diagnosis of WPW syndrome is established in the presence of a combination of ECG signs of ventricular preexcitation with paroxysms of tachyarrhythmia.

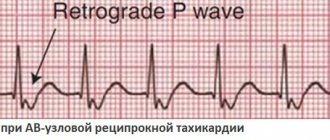

In the majority of patients (90%), doctors record this type of atrioventricular reciprocal tachycardia, in which the excitation wave propagates anterogradely through the atrioventricular node to the ventricles and retrogradely through the accessory tract to the atrium. This tachycardia is called orthodromic.

Much less often (5-10%) one can observe a variant of atrioventricular reciprocal tachycardia, in which the excitation wave makes a circular motion along the same loop, but in the opposite direction: anterograde along the AP to the ventricles and retrograde through the atrioventricular node to the atrium - this tachycardia is called antidromic.

The ECG records a paroxysm with extended f.i.8 complexes, more than 0.1 s (like the most pronounced preexcitation, “ventricular type”) with a frequency of 150-200 per minute.

Symptoms of ventricular tachycardia

Symptoms depend on the duration of the attack and the complexity of the disorders. Sometimes VT is asymptomatic.

The main ailments include:

- cardiopalmus;

- pain and burning in the chest;

- severe dizziness;

- loss of consciousness;

- convulsions;

- weakness;

- anxiety or feeling of fear.

To be sure that your heart is working properly and to eliminate the cause of VT symptoms in a timely manner, consult our specialists. The Cardiology Center of the Federal Scientific and Clinical Center of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency has developed several heart examination programs. Cardiologists will select the right program for you and prescribe appropriate diagnostics.

Risk of atrial fibrillation and flutter

Of particular danger is the occurrence of atrial fibrillation and flutter in patients with DPP and conduction of impulses along abnormal pathways anterogradely from the atria to the ventricles.

The risk of ventricular fibrillation can be increased, among other things, by the use of drugs that accelerate conduction through the AP. First of all, this applies to veralamil and digoxin, which precludes their use in the antidromic version of paroxysmal tachycardias. At the same time, the drugs of choice in the treatment of patients with paroxysmal tachycardia and widened QRS complex in WPW syndrome are drugs of class I (procainamide, disopyramide, propafenone) and class III (amiodarone).

It is often necessary to differentiate tachycardia with a wide QRS complex in WPW syndrome and paroxysm of ventricular tachycardia, which can be extremely difficult to do using an external ECG and requires transesophageal ECG diagnostics.

A very high ventricular rate (more than 200 per minute), the occurrence of tachycardia paroxysms in childhood and adolescence (often in patients without structural changes in the myocardium), and the presence of tachycardia attacks in close relatives may indicate to the doctor the possibility of the existence of DPP.

Causes of ventricular tachycardia

In 98%, the cause of VT is a heart disease, in the remaining 2% the cause remains undetected. This pathology is called idiopathic.

Diseases that can lead to VT:

- myocardial infarction;

- post-infarction aneurysm;

- reperfusion arrhythmias;

- myocarditis;

- cardiosclerosis;

- cardiomyopathy;

- sarcoidosis;

- heart defects;

- genetic diseases

Let us note the provoking external factors influencing the development of VT:

- stressful situations;

- frequent psycho-emotional stress;

- increased physical activity;

- surgical intervention;

- drug overdose;

- hormonal imbalance in the body.