The prevalence of chronic and incidence of acute aortic regurgitation (AR) remain unclear to date. Singh et al., conducting a duplex echocardiographic study (2DECHO-CG) in the Framingham study cohort, identified chronic AR in 13% of men and 8.5% of women. In most cases, it was represented by a mild degree of AR. Risk factors for AR were male gender and old age. At the same time, arterial hypertension (AH) did not affect the incidence of AR, but contributed to a moderate expansion of the aortic root. In another study (Strong Heart Study), the prevalence of AR in the US native population was 10%. The majority of cases were represented by mild and moderate severity of AR. Independent risk factors were age and aortic root diameter, and no gender differences were found. At the same time, it is known that patients over the age of 50 years have an increased risk of AR progression and early death. A feature of the course of AR is a long asymptomatic period, which makes its timely detection difficult. Since the establishment of AR, according to instrumental studies, the rate of appearance of clinical symptoms of chronic heart failure is 3.5%, systolic dysfunction of the left ventricular myocardium is 6%, and the risk of sudden death increases by 0.2% annually.

General information

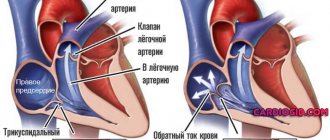

Normally, the heart valves, located between the chambers and vessels, provide a barrier to the return of blood. The valves are designed in such a way that their leaflets respond to the pressure of the blood flow and mechanically close. When the valves malfunction, they do not close completely, causing a hole to appear and blood returning back. The aortic valve is located at the exit of the left ventricle, so when it is not completely closed, it is this heart chamber that receives excess blood volume. Regurgitation is more common in men than in women, and it can not only be a normal variant, but also be related to heart defects. Thus, in every tenth case of heart disease, patients also have aortic regurgitation.

Etiology

Aortic regurgitation can be caused either by primary damage to the aortic valve leaflets or by damage to the aortic root, which currently accounts for more than 50% of all cases of isolated AR (Table 1).

Valve damage

- Rheumatic fever is one of the main valvular causes of AR. Wrinkling of the leaflets due to infiltration by connective tissue prevents their closure during diastole, thereby forming a “defect” in the center of the valve, which is a window for regurgitation of blood into the LV cavity. Concomitant fusion of the commissures limits the opening of the aortic valve, which leads to the appearance of concomitant aortic stenosis (AS).

- Infectious endocarditis. AR may be caused by valve destruction, perforation of its leaflets, or the presence of growing vegetations that prevent the leaflets from closing in diastole.

- Calcified AS in elderly people leads to the development of AR in 75% of cases, both due to age-related expansion of the fibrous ring of the aortic valve and as a result of aortic dilatation.

- Other primary valvular causes of AR are:

- trauma leading to rupture of the ascending aorta. In this case, the attachment of the commissures is disrupted, which leads to prolapse of the aortic cusp into the LV cavity;

- congenital bicuspid valve due to incomplete closure or prolapse of its valves;

- large septal defect of the interventricular septum;

- membranous subaortic stenosis;

- complication of radiofrequency catheter ablation;

- myxomatous degeneration of the aortic valve;

- destruction of the biological valve prosthesis.

Aortic root damage

Diseases that can cause aortic root damage include: age-related (degenerative) dilatation of the aorta, cystic necrosis of the aortic media (isolated or as a component of Marfan syndrome), aortic dissection, osteogenesis imperfecta (osteopsatyrosis), syphilitic aortitis, ankylosing spondylitis, Behçet's syndrome, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis arthritis, relapsing polychondritis, Reiter's syndrome, giant cell arteritis, systemic hypertension, and the use of certain appetite suppressants.

AR in these cases is formed due to pronounced expansion of the aortic valve ring and aortic root with subsequent separation of the leaflets. Subsequent dilatation of the root is inevitably accompanied by excessive tension and bending of the valves, which then thicken, wrinkle and become unable to completely cover the aortic opening. This, in turn, aggravates AR, leads to further expansion of the aorta and closes the vicious circle of pathogenesis (“regurgitation increases regurgitation”).

Regardless of the cause, AR always causes dilatation and hypertrophy of the left ventricle, with subsequent dilation of the mitral annulus and the possible development of left atrium dilatation. Often, “pockets” form on the endocardium at the site of contact between the regurgitant flow and the LV wall.

Regurgitation in normal and pathological states

Regurgitation itself is not scary and does not cause problems for the body’s functioning if its volume is insignificant. Aortic regurgitation of the 1st degree does not at all lead to the ventricle suffering. Therefore, cardiologists do not consider this type of regurgitation as a pathology.

When monitoring cardiac activity using an ultrasound machine, regurgitation can be detected to a small extent and generally not affect blood circulation. Such regurgitation can be congenital and does not pose a danger to the person who has it. Acquired regurgitation occurs as a result of previous diseases. Most often, the following pathologies lead to it:

- rheumatism;

- infective endocarditis.

As a result of these diseases, cicatricial changes in the valves are formed, as a result of which the valve ceases to fully perform its functions. Therefore, with acquired regurgitation of the aortic valve, it is very important to know how severe the reverse reflux of blood is, i.e. how much the left ventricle suffers from its excess volume. In some cases, the pathology leads not just to significant non-closure, but to complete destruction of the aortic valve leaflets. Then they talk about regurgitation of 2–3 degrees.

Diagnostics

Electrocardiography

Chronic severe AR leads to deviation of the heart axis to the left and the appearance of signs of diastolic volume overload, which is expressed in a change in the shape of the initial components of the ventricular complex (pronounced Q waves in lead I, AVL, V3-V6) and a decrease in the R wave in lead V1. Over time, these signs decrease and the overall amplitude of the QRS complex increases. Inverted T waves and ST segment depression are often detected, which reflects the severity of LV hypertrophy and dilatation. Acute AR is characterized by nonspecific changes in the ST segment and T wave in the absence of signs of LV myocardial hypertrophy.

X-ray of the chest organs

In typical cases, there is an expansion of the heart shadow downwards and to the left, which leads to an increase in its size along the longitudinal axis and a slight increase in diameter. Aortic valve calcification is not typical for isolated AR, but is often found in association with AS. A distinct increase in the size of the left atrium, in the absence of signs of heart failure, speaks in favor of the presence of concomitant damage to the mitral valve. Severe aneurysmal dilatation of the aorta suggests aortic root involvement (eg, Marfan syndrome, cystic medial necrosis, or annuloaortic ectasia) as the cause of AR. Linear calcification of the wall of the ascending aorta is observed in syphilitic aortitis, but it is very nonspecific and may be present in degenerative lesions.

Echocardiography

It is recommended for patients with AR and is carried out for: verification and assessment of the severity of acute or chronic AR, determination of its cause, severity of LV hypertrophy and central hemodynamic parameters, as well as for dynamic monitoring and determination of the rate of progression in asymptomatic patients (Class I). In asymptomatic patients with normal LV function and size, 2ECHO-CG should be performed annually. If clinical symptoms appear and/or the size of the LV increases (LV EDV 60–70 mm), the study is performed every 6 months. Patients with severe AR and severe LV dilatation (LV EDV greater than 70 mm) should be referred to a cardiac surgeon. Body surface area should be considered when stratifying patients, as significant LV dilatation may not be observed in women and short men.

Additional ECHO-CG techniques to assess the severity of AR

- When examining in color Doppler scanning mode, either the area of the initial jet at the aortic valves is measured during a parasternal examination of the aortic valve along the short axis (in severe AR, this area exceeds 60% of the area of the fibrous ring) or the thickness of the initial part of the jet during a parasternal position of the sensor and examination of the aorta along the long axis axes. In severe AR, the transverse size of the initial jet is >60% of the size of the aortic valve annulus.

- The half-life of the AR Doppler spectrum is determined when examined using continuous-wave Doppler; if it is <400 ms, then regurgitation is considered severe.

- Using continuous wave Doppler, the magnitude of the slowdown in the decline on the Doppler spectrum of the aortic insufficiency jet is determined; if this indicator is >3.0 m/s, AR is considered severe (the value of the last two indicators largely depends on heart rate).

- The presence of LV dilatation also indicates severe aortic insufficiency.

- Finally, with severe AR, reverse blood flow appears in the ascending aorta.

All of the above signs can describe severe AR, but there are no signs that reliably separate mild AR using Doppler ECHO-CG from moderate AR.

In addition, the four-degree division of the AR jet is also used in everyday practice:

I Art. — the regurgitation jet does not extend beyond ½ the length of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve;

II Art. - the AR jet reaches or reaches the longest end of the mitral valve leaflet;

III Art. — the jet reaches ½ the length of the LV;

IV Art. - the jet reaches the apex of the LV. If the results of 2DECHO-CG studies are uninformative, radionuclide angiography or MRI is performed.

Cardiac catheterization is indicated in two clinical situations:

- In case of discrepancy between the results of non-invasive studies (2ECHO-CG, MRI).

- Before performing aortic valve replacement surgery in patients with a high risk of cardiovascular complications, as well as during simultaneous CABG surgery in patients with coronary artery disease (in combination with coronary angiography). The severity of AR is assessed according to the criteria presented in Table 4.

Natural course

Depends on the form and severity of AR. In acute AR, early death without timely surgical intervention occurs due to acute left ventricular failure.

With moderate or severe chronic AR, the prognosis is favorable for many years. About 75% of patients live more than 5 years after diagnosis, about 50% live more than 10 years. Without surgical treatment, death usually occurs within 4 years after the onset of angina and within 2 years after the development of heart failure. In the presence of LV systolic dysfunction, the likelihood of symptoms occurring is more than 25% per year, and the need for aortic valve replacement (AVR), even in asymptomatic patients, occurs within 2-3 years. The key point in the management of patients with AR is monitoring of 2 echocardiographic parameters - LV EDR and ejection fraction. If their dynamics are negative, patients should be referred to a cardiac surgeon to resolve the issue of performing AVR, regardless of the clinical picture. Asymptomatic patients with a normal ejection fraction have a long-term favorable prognosis.

Treatment

Treatment goals:

- Prevention of sudden death and heart failure.

- Relieving symptoms of the disease and improving quality of life.

Drug treatment

The main goal of drug therapy is to reduce systolic blood pressure and reduce the volume of regurgitation. The drugs of choice are vasodilators of various classes (nifedipine, ACE inhibitors and hydralazine). Vasodilators are used for:

- Long-term treatment of patients with severe AR who have symptoms of the disease or LV dysfunction if surgical treatment is not recommended due to the presence of additional cardiac or noncardiac causes.

- Short-term therapy to improve the hemodynamic profile of patients with severe symptoms of heart failure and severe AR before undergoing AVR.

- Reducing the rate of progression of clinical symptoms in patients with severe AR, in the presence of dilatation of the LV cavity, but with a normal LV ejection fraction.

Due to the favorable prognosis, vasodilators are not indicated in asymptomatic patients with mild or moderate AR and normal LV systolic function.

Indications for surgical treatment

AVR is indicated for patients with severe AR, taking into account the clinical picture of the disease, the presence of LV systolic dysfunction and planned cardiac surgery (on the coronary arteries, aorta or other heart valves).

In addition, AVR is justified in asymptomatic patients with severe AR and normal LV systolic function (ejection fraction more than 50%), but with severe LV dilatation (EDR - more than 75 mm or ESR - more than 55 mm).

Causes of aortic regurgitation

Before understanding how to eliminate aortic regurgitation in case of progression, it is necessary to determine the causes of this condition. With minor non-closure, treatment may not be required; it is only important to be promptly examined by a doctor and undergo diagnostics at the specified time. As for the causes of pathological regurgitation, for which you need to sound the alarm, among them are:

- rheumatic heart disease;

- bacterial sepsis;

- endocarditis caused by influenza, measles, scarlet fever, pneumonia, cancer;

- congenital valve pathologies;

- autoimmune lesions;

- myocardial infarction;

- serious injuries to the chest, heart with rupture of the muscles adjacent to the valve;

- performing radiofrequency ablation;

- age-related changes causing aortic damage;

- Marfan syndrome, which affects the base of the valve - the connective tissue;

- dissection of the walls of the aortic aneurysm;

- giant cell arteritis;

- inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis, syphilis;

- cardiomyopathies of various kinds.

What happens with regurgitation?

When blood is pumped into the ventricle, it gradually stretches and increases in volume. With long-term pathology, the mitral ring also undergoes expansion, which invariably leads to an increase in the size of the atrium. As a result of constant overload of the left ventricle, persistent stretch marks are formed. Pathological regurgitation can take on acute or chronic forms. Acute regurgitation occurs when a person’s health suddenly deteriorates - trauma, endocarditis, dissecting aneurysm.

This form is characterized by a rapid flow of blood into the left ventricle, in which the body does not have time to compensate for the load. It increases sharply and the work of not only the left side of the heart becomes difficult, but in general the entire heart muscle suffers. The aorta, in turn, does not receive enough blood. The general blood circulation of the body suffers. In the event of such disorders, patients develop pulmonary edema and/or cardiogenic shock. Symptoms are significantly aggravated by hypertension and dissection of the aortic aneurysm.

In the chronic form of the disease, compensatory mechanisms restrain the pathology for a long time and prevent its symptoms from appearing. However, despite adaptation to the situation of the left ventricle, after some time a stage of decompensation occurs and patients develop heart failure.

Clinical manifestations

Acute aortic regurgitation

As a rule, the first clinical manifestation of acute AR is cardiogenic shock caused by the limited adaptive capacity of the myocardium to sharply increased filling volumes. Patients develop severe hypotension and weakness (decreased stroke volume), as well as shortness of breath with the subsequent development of alveolar pulmonary edema (increased pressure in the left atrium and pulmonary vessels).

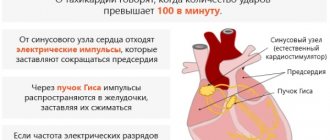

Chronic aortic regurgitation

Chronic AR is characterized by a long asymptomatic period, during which progressive expansion of the LV cavity occurs. Clinical signs characteristic of a decrease in cardiac reserve or myocardial ischemia develop, as a rule, in the fourth or fifth decade of life after the formation of severe cardiomegaly and myocardial dysfunction. The early complaint is shortness of breath with a progressive decrease in exercise tolerance with the development of cardiac asthma. Angina appears in the later stages of the disease; attacks of “nighttime” angina become painful and are accompanied by profuse cold, sticky sweat, which is caused by a slowdown in heart rate and a critical drop in diastolic blood pressure. Patients with AR often complain of “heartbeat” intolerance, especially in a horizontal position, as well as intractable chest pain caused by the heart beating against the chest. Tachycardia, which occurs during emotional stress or during exercise, causes palpitations and head swaying. Of particular concern to patients are ventricular extrasystoles due to a particularly strong post-extrasystolic contraction against the background of an increase in LV volume.

When examined in patients with chronic AR, the most common symptoms observed are head swaying, coinciding with systole (Musset's symptom), and a "collaptoid" pulse ("hydraulic pump" pulse), characterized by a rapid expansion and decline of the pulse wave (Corrigan's pulse). Peripheral pulses are best assessed at the radial artery of the patient's raised arm. Other auscultatory signs of chronic AR are presented in Table 2.

Pulse blood pressure is typical. Often, Korotkoff sounds continue to be heard even around zero, although intra-arterial pressure rarely drops below 30 mm Hg. Art. The apical impulse is diffuse and hyperdynamic, displaced downward and outward; Systolic retraction of the parasternal region may be observed. At the apex, a wave of rapid filling of the LV can be detected, as well as systolic vibration at the base of the heart, the supraclavicular fossa, over the carotid arteries - which is a consequence of increased cardiac output. In many patients o.

In contrast to chronic AR, there are no auscultatory phenomena in acute AR. The patient's condition deteriorates sharply, always severe, due to the development of cardiogenic shock and acute left ventricular failure. In this case, a weakening of the first sound above the apex of the heart due to premature closure of the mitral valve, signs of pulmonary hypertension with an emphasis on the pulmonary component of the second sound, and the appearance of the third and fourth heart sounds are determined. In the absence of emergency cardiac surgery, the prognosis is poor.

The cardinal clinical sign of chronic AR is diastolic murmur, starting immediately after the second sound. It is distinguished from the murmur of pulmonary regurgitation by its early onset (i.e., immediately after the second sound) and the presence of increased pulse pressure. The murmur is best heard while sitting or when the patient bends forward, holding the breath at the height of exhalation. With severe AR, the noise quickly reaches a peak and then slowly decreases throughout diastole (decrescendo). If regurgitation is caused by a primary valve lesion, the murmur is best heard at the left sternal border in the third or fourth intercostal space. However, if the murmur is due primarily to dilatation of the ascending aorta, the auscultatory maximum will be the right sternal border.

The severity of AR is most correlated with the duration of the murmur, rather than with its severity. With moderate AR, the murmur is usually limited to early diastole, high-frequency, and resembles a jolt. With severe AR, the murmur lasts throughout diastole and can acquire a “grinding” tone. When the noise becomes musical (the cooing of a dove), it usually indicates a kinked or perforated aortic valve leaflet. In patients with severe AR and left ventricular decompensation, equalization of pressure in the LV and aorta at the end of diastole leads to the disappearance of this musical component of the noise.

Mid- and late-diastolic murmur at the apex (Austin-Flint murmur) is a fairly common finding in severe AR; it can appear with an unchanged mitral valve. The murmur is caused by the presence of resistance to mitral blood flow by high pressure in the LV cavity, as well as vibration of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve under the influence of regurgitant aortic flow. In practice, it is difficult to distinguish an Austin-Flint murmur from the murmur of mitral stenosis. Additional differential diagnostic criteria in favor of the latter are the strengthening of the first sound (popping first sound) and the sound (click) of the opening of the mitral valve. Differences in clinical signs of acute and chronic AR are presented in Table 3.

Symptoms of regurgitation

If a patient develops acute regurgitation, then symptoms of cardiogenic shock occur, which are characterized by:

- sudden weakness;

- sudden pallor of the skin;

- decreased blood pressure;

- shortness of breath;

- disturbance of consciousness.

If pulmonary edema develops, the symptoms are complicated by wheezing when inhaling, lack of air, and attacks of suffocation. There may be a cough with sputum and blood in it. The patient's lips, face and hands rapidly turn blue.