Classification of pathology

This disease is often also called late toxicosis, but this name is incorrect. Unlike toxicosis, gestosis requires treatment, since it is not a normal variant. Depending on the severity of symptoms, there are 4 stages of the disease:

- Dropsy. It often goes unnoticed, as it is characterized only by swelling.

- Nephropathy. In addition to swelling, a pregnant woman may find protein in her urine. At this stage, kidney damage occurs; if left untreated, complications may arise.

- Preeclampsia. Characterized by increased blood pressure and accompanying symptoms: headache, nausea, etc. Possible disruption of cerebral blood supply.

- Eclampsia. This stage is the most dangerous. A pregnant woman often experiences convulsions, placental abruption, heart attack and other serious consequences can occur.

Links[edit]

- ^ abc Page 264 in: Grezele, Paolo (2008). Platelets in hematologic and cardiovascular diseases: a clinical reference

. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-88115-3. - ^ abcdefgh Hypercoagulation during pregnancy. A publication of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Cincinnati. September / October 2002 Volume 8, Issue 5

- ↑

de Boer K, ten Cate JW, Sturk A, Borm JJ, Treffers PE (1989).

"Increased thrombin formation in normal and hypertensive pregnancy." Am J Obstet Gynecol

.

160

(1):95–100. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9378 (89) 90096-3. PMID 2521425. - "Venous thromboembolism (blood clots) and pregnancy". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Abdul Sultan, A.; West, J.; Tata, LJ; Fleming, KM; Nelson-Piercy, C.; Grange, M. J. (2013). "Risk of first venous thromboembolism in pregnant women in hospital: a population-based cohort study from England". BMJ

.

347

: f6099. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.f6099. PMC 3898207. PMID 24201164. - Eichinger, S.; Evers, J.L.H.; Glasier, A.; La Vecchia, C.; Martinelli, I.; Skouby, S.; Somigliana, E.; Baird, D.T.; Benagiano, G.; Crosignani, P.G.; Gianaroli, L.; Negri, E.; Volpe, A.; Glasier, A.; Crosignani, P. G. (2013). "Venous thromboembolism in women: a particular risk to reproductive health". Human Reproduction Update

.

19

(5): 471–482. DOI: 10.1093/humupd/dmt028. PMID 23825156. - ^ B de Vries PSO, van Pampus MG, Hague WM, Bezemer PD, Joosten JH, FRUIT Researchers (2012). "Low molecular weight heparin added to aspirin to prevent relapse of early-onset preeclampsia in women with hereditary thrombophilia: FRUIT-RCT". J. Thromb.

Gemost .

10

(1): 64–72. DOI: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04553.x. PMID 22118560. - McNamee, Kelly; Daud, Feroza; Farquharson, Roy (1 August 2012). "Recurrent miscarriage and thrombophilia." Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology

.

24

(4): 229–234. DOI: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32835585dc. PMID 22729089. - ^ abcdefghi "Hemostasrubbningar inom obstetrik och gynekologi" (Disorders of hemostasis in obstetrics and gynecology), from ARG (working and reference group) from SFOG (Swedish Association of Obstetrics and Gynecology). An introduction is available at [1]. Updated 2012

- Giannubilo, S.R.; Tranquilli, A.L. (2012). "Anticoagulant therapy during pregnancy for acquired and hereditary thrombophilia in the mother and fetus." Modern medicinal chemistry

.

19

(27): 4562–71. DOI: 10.2174/092986712803306466. PMID 22876895. - Sathienkijkanchai A, Wasant P (2005). "Warfarin syndrome of the fetus." J Med Assoc Thailand

.

88

(Suppl 8):S246–50. PMID 16856447. - Schaefer S, Hannemann D, Meister R, ELEFANT E, Paulus W, Flask T, Reuvers M, Robert-Gnansia E, Arnon J, De Santis M, Clementi M, Rodriguez-Pinilla E, Dolivo A, Merlob R (2006). “Vitamin K antagonists and pregnancy outcome. Multicenter prospective study." Thromb Haemost

.

95

(6):949–57. DOI: 10.1160/TH06-02-0108. PMID 16732373. - ^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstu vw [2] Archived June 12, 2010 at the Wayback Machine Therapeutic anticoagulation during pregnancy.

Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital (NHS Trust). Registration number CA3017. June 9, 2006 [reviewed June 2009] - Couto E, Nomura ML, Barini R, Pinto e Silva JL (2005). "Pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism in combined heterozygous factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A mutations". Sao Paulo Med J

.

123

(6):286–8. DOI: 10.1590/S1516-31802005000600007. PMID 16444389. - De Jong, PG; Goddijn, M.; Middeldorp, S. (2013). "Antithrombotic therapy for miscarriage". Human Reproduction Update

.

19

(6):656–673. DOI: 10.1093/humupd/dmt019. PMID 23766357. - Shaul WL, Emery H, Hall JG (1975). "Chondrodysplasia punctata and maternal warfarin during pregnancy." Am J Dis Child

.

129

(3):360–2. DOI: 10.1001/archpedi.1975.02120400060014. PMID 1121966. - James AH, Grotegut CA, Brancazio LR, Brown H (2007). “Thromboembolism during pregnancy: relapses and their prevention.” Semin Perinatol

.

31

(3): 167–75. DOI: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.03.002. PMID 17531898. - Kim BJ, An SJ, Shim SS, Jun JK, Yoon BH, Syn HC, Park JS (2006). "Pregnancy outcomes in women with mechanical heart valves." J Reprod Med

.

51

(8): 649–54. PMID 16967636. - Iturbe-Alessio I, Fonseca MC, Mutchinik O, Santos MA, Zajarías A, Salazar E (1986). "Risks of anticoagulant therapy in pregnant women with artificial heart valves." N Engl J Med

.

315

(22):1390–3. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM198611273152205. PMID 3773964. - Salazar E, Izaguirre R, Verdejo J, Mutchinick O (1996). "Failure to adhere to adjusted doses of subcutaneous heparin to prevent thromboembolic events in pregnant women with mechanical prosthetic heart valves." J Am Coll Cardiol

.

27

(7):1698–703. DOI: 10.1016/0735-1097 (96) 00072-1. PMID 8636556. - Ginsberg JS, Chan WS, Bates SM, Kaatz S (2003). "Anticoagulation of pregnant women with mechanical heart valves" (PDF). Arch Intern Med

.

163

(6):694–8. DOI: 10.1001/archinte.163.6.694. PMID 12639202.

Publications in the media

Antiphospholipid syndrome is a clinical and laboratory symptom complex that includes venous and/or arterial thrombosis, various forms of obstetric pathology (primarily recurrent miscarriage), thrombocytopenia, as well as a variety of neurological, skin, cardiovascular, and hematological disorders. A characteristic immunological sign of APS is antibodies to phospholipids. APS develops more often against the background of SLE (secondary APS) or in the absence of other systemic autoimmune pathology (primary APS).

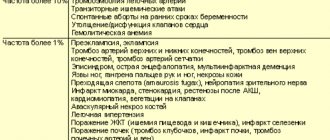

Statistical data. Frequency: 30–60% of patients with SLE. The frequency of detection of antiphospholipid antibodies (APS-AB) in the general population is 2–4%. The predominant age is 20–40 years. The predominant gender is female.

The etiology is unknown. A transient increase in APS-AT is observed against the background of bacterial and viral infections (hepatitis C, HIV, infective endocarditis, malaria), which, however, are rarely accompanied by thrombosis. Currently, the immunogenetic features of APS continue to be clarified. In a number of studies, APS-AT was detected in the sera of relatives of patients with APS. Suggestions have been made about the connection of APS with HLA-DR4, HLA-DR7, HLA-DRw53.

Pathogenesis. APS-ATs bind to phospholipids in the presence of b2-glycoprotein I, which has anticoagulant activity. In this case, the balance of procoagulant and anticoagulant factors in the blood plasma shifts towards procoagulation (the synthesis of antithrombin III, annexin V is suppressed and, on the contrary, the synthesis of thromboxane, platelet activating factor, antibodies to prothrombin, protein C, protein S, etc. is enhanced).

Classification

• Primary APS (in this case there is no connection with any disease that can cause the formation of APS-AT). Primary APS with a predominance of central nervous system damage is also called Sneddon syndrome.

• Secondary APS (against the background of another systemic autoimmune disease).

• Catastrophic APS (severe, often fatal condition, characterized by multiple thromboses and infarctions of internal organs, developing over days or weeks). Often provoked by abrupt withdrawal of indirect anticoagulants.

Clinical picture • Recurrent thrombosis •• Venous (thrombophlebitis of the deep veins of the leg, Budd-Chiari syndrome, pulmonary embolism) •• Arterial: thrombosis of the coronary arteries with the development of MI; thrombosis of intracerebral arteries. Recurrent microstrokes can manifest as masks of convulsive syndrome, dementia, mental disorders • Obstetric pathology caused by thrombosis of placental vessels •• Recurrent spontaneous abortions •• Intrauterine fetal death • Eclampsia • Chorea • Hematological disorders •• Hemolytic anemia (positive Coombs test) •• Thrombocytopenia, rarely accompanied by hemorrhagic syndrome •• Evans syndrome (a combination of hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia) • Thrombotic non-infectious endocarditis varies from minimal, detected only on echocardiography, to severe valve damage requiring differential diagnosis with infective endocarditis. The mitral valve is most often affected. Accompanied by embolisms in the vessels of the brain • Arterial hypertension •• Labile arterial hypertension associated with livedo reticularis and involvement of the central nervous system •• Stable arterial hypertension against the background of thrombosis of the renal arteries or abdominal aorta • Lung damage: pulmonary hypertension as an outcome of secondary pulmonary embolism • Kidney damage: thrombotic microangiopathy with the development of renal failure • Adrenal insufficiency as a result of thrombosis of the adrenal arteries (rarely) • Aseptic necrosis of bones (femoral head) • Skin lesions: livedo reticularis, less commonly purpura, palmar and plantar erythema, gangrene of the fingers as a result of thrombosis of the arteries of the extremities.

Laboratory data • Presence of antibodies to cardiolipin (class IgG and IgM) in blood plasma; detected using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent method • Detection of lupus anticoagulant in the blood (ATs that block phospholipid-dependent blood coagulation factors in vitro, see details below in the diagnostic criteria) • False-positive von Wassermann reaction • Presence of ANAT (50% of cases) • Thrombocytopenia • Positive Coombs test with hemolytic anemia.

Instrumental data • CT or MRI - to confirm thrombosis in the central nervous system or abdominal cavity • EchoCG - thrombotic lesions on the valve leaflets (usually the mitral valve).

Diagnostic criteria (preliminary criteria for the classification of APS, 1999)

To make a reliable diagnosis of APS, at least 1 clinical and 1 laboratory criterion are required.

Clinical criteria

1. Vascular thrombosis.

• One or more episodes of arterial, venous or small vessel thrombosis supplying any organ or tissue. With the exception of superficial vein thrombosis, thrombosis must be confirmed by X-ray or Doppler angiography or morphologically. With morphological confirmation, signs of thrombosis are revealed in the absence of pronounced inflammatory infiltration of the vascular wall.

2. Obstetric pathology.

(a) One or more unexplained deaths of a morphologically normal fetus before 10 weeks of gestation, or

(b) One or more episodes of premature death of a morphologically normal fetus before 34 weeks of gestation due to severe preeclampsia or eclampsia or severe placental insufficiency.

(c) Three or more episodes of unexplained sequential spontaneous abortion before 10 weeks of pregnancy, with the exception of anatomical and hormonal disorders in the mother and chromosomal disorders of the mother and father.

Laboratory criteria

1. Detection in blood serum using a standardized immunoenzyme method (allowing the determination of b2-glycoprotein-dependent antibodies) at least 2 times within 6 weeks of antibodies to cardiolipin IgG or IgM in medium or high titers.

2. Detection of lupus anticoagulant in blood plasma at least 2 times within 6 weeks using a standardized method, including several stages.

(a) Prolongation of phospholipid-dependent blood coagulation using a screening test (activated PTT, kaolin test, Russell's viper venom test, PT).

(b) Failure to correct prolonged clotting time in screening tests when mixed with normal platelet-free plasma.

(d) Rule out other coagulopathies (factor VIII inhibitors or heparin).

Differential diagnosis • DIC syndrome has a similar clinical picture with catastrophic APS, however, in contrast, catastrophic APS is most often provoked by the abrupt withdrawal of indirect anticoagulants and is accompanied by a high concentration of APS-AT in the blood • Infectious endocarditis is accompanied by fever, detection of the pathogen in the blood. It is possible to detect APS-AT in low concentrations for a short period of time • Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura resembles APS in the presence of hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, damage to the central nervous system and kidneys. However, with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, APS-AT and no significant changes in the coagulogram are detected; This disease is characterized by the detection of fragmented red blood cells in the blood and Coombs-negative anemia.

TREATMENT

General tactics. The main goal of treatment is to prevent thrombosis. The benefit of primary prevention (prescription of acetylsalicylic acid when APS-AT is detected before the development of thrombosis) has not been proven. Treatment for significant APS is lifelong.

Mode. Prolonged immobile conditions (for example, long air flights) should be avoided to avoid provoking thrombosis. Persons taking indirect anticoagulants should not engage in traumatic sports. Oral contraceptives should not be used. Women should understand that when planning pregnancy, warfarin must be replaced with a combination of heparin and acetylsalicylic acid before conceiving a child.

Diet. If the patient is taking warfarin, the intake of foods containing vitamin K should be limited.

Drug treatment • Indirect anticoagulants. Recurrent thrombosis is an indication for the prescription of indirect anticoagulants (warfarin at an initial dose of 2.5–5 mg/day, followed by maintaining the INR in the range of 2.5–3.0). The use of warfarin should not be abruptly discontinued to avoid the development of catastrophic APS • Direct anticoagulants. Heparin is used in pregnant women (see below) or for the treatment of developing thrombosis •• Unfractionated heparin starting dose of 80 units/kg, then 18 units/kg/hour. Control of activated PTT •• Low molecular weight heparin 1 mg/kg/day, there is no need for regular monitoring of hemostasis indicators • Antiplatelet agents. APS is an indication for the use of low doses of acetylsalicylic acid (75–80 mg/day). It is possible to use clopidogrel, ticlopidine, dipyridamole, but there is no evidence. • Aminoquinoline derivatives are used in patients with SLE, because have antithrombotic and hypolipidemic activity; the drug of choice is hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/day • GC. One should remember about the hypercoagulable properties of GC, therefore, when treating the underlying disease in secondary APS, it is necessary to strive to use lower doses of drugs. GCs are prescribed for thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, or (in pulse therapy mode) for the treatment of catastrophic APS • Immunosuppressants. Cyclophosphamide is suggested at a dose of 2–3 mg/kg/day (no evidence available) • IV immunoglobulin is used in the treatment of catastrophic APS, APS in pregnancy and APS with thrombocytopenia (0.2–2 g/kg/day for 4– 5 days).

Features in pregnant women • Indirect anticoagulants are contraindicated! • Acetylsalicylic acid is prescribed from the second trimester of pregnancy at 80 mg/day • Heparin is prescribed from the first weeks of pregnancy, discontinued 12 hours before the expected birth, after birth it is used for another 10-12 days (there are recommendations for continuing heparin therapy throughout the lactation period) •• unfractionated heparin 5000 IU 2–3 times/day •• low molecular weight heparin 1 mg/kg/day • IV immunoglobulin is used when combination therapy with heparin and acetylsalicylic acid 400 mg/kg/day for 5 days or 1000 mg is ineffective /kg/day 1–2 days • In resistant cases, a positive effect of plasmapheresis has been described, however, there is a danger of provoking catastrophic APS.

Complications • CNS lesions: strokes, dementia • Renal damage: renal failure • MI (more often in men) • Gangrene of the distal extremities.

Forecast. Thrombocytopenia, arterial thrombosis, a persistent increase in antibody titers to cardiolipin, smoking, taking oral contraceptives, arterial hypertension, and rapid withdrawal of indirect anticoagulants are considered unfavorable prognostic factors for the recurrence of thrombosis.

Synonym • Huge's syndrome • Anticardiolipin AT syndrome.

Reduction. APS-AT - antiphospholipid AT.

ICD-10 • D89.9 Disorder involving the immune mechanism, unspecified