Why is this necessary?

If you have suffered deep vein thrombosis of the lower or upper extremities, your doctor will most likely prescribe you indirect anticoagulants.

The main drug in this group today, both here and abroad, is warfarin. In our country, another drug of this group is used quite widely - phenylin. Other coumarin drugs (acenocoumarol, marcumar, marivan) can be used. The recommendations given are mostly applicable to any anticoagulant. The purpose of this medication is to prevent blood clots from recurring, which could cause your condition to worsen or cause life-threatening complications. The risk of recurrence of thrombosis is quite high during the first year after the first episode of the disease, therefore, taking into account various factors, warfarin is prescribed for a period of 2 to 12 months. In rare cases, longer therapy is performed. Indirect anticoagulants have no effect on an already formed blood clot.

To determine the duration of treatment, special (including genetic) blood tests are sometimes required to identify an increased tendency to blood clots.

A very large number of patients around the world receive the treatment you have prescribed. It is used not only in phlebology, but also in such areas of medicine as vascular surgery. In addition to deep vein thrombosis, the basis for prescribing anticoagulant therapy is often previous heart attacks, cardiac arrhythmias, valve and peripheral vessel replacement, and much more.

Warfarin or Aspirin Cardio – which is better?

Manufacturer: Bayer, Germany

Release form: film-coated tablets

Active ingredient: Acetylsalicylic acid

Synonyms: Thrombo ACC, Thrombopol, CardiASK, ASC Cardio

Warfarin analogue Aspirin Cardio is an original German drug that has an antiplatelet effect by blocking the enzyme cyclooxygenase-1, and thus preventing platelet aggregation.

The analogue of Aspirin Cardio is used mainly for prophylactic purposes to prevent cerebrovascular accidents, stroke, acute myocardial infarction, and complications after vascular surgery.

One of the indications for the use of the Aspirin Cardio analogue is stable and unstable angina.

The active ingredient Acetylsalicylic acid in doses of 500 mg has an analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory effect.

How to monitor treatment

Carrying out antithrombotic (anticoagulant) therapy can save your life and health, but requires increased attention and mandatory compliance with the doctor’s recommendations. Warfarin is a drug that reduces the ability of blood to clot, so its excess can lead to hemorrhagic complications, i.e. to bleeding. To avoid complications, the required dose of warfarin is monitored using a blood test called INR (International Normalized Ratio). This may sometimes be referred to as INR in laboratory responses. During the entire period of taking warfarin, the INR should be in the range of 2.0 - 3.0. If the INR is less than 2.0, then blood clotting is not reduced and thrombotic complications are possible. If the INR is more than 4.0, hemorrhagic complications are very real. An increase in INR from 2.5 to 4.0 indicates the need to reduce the dose of the drug, but usually does not pose a direct threat. For some diseases, the required upper limit of INR is 4.0 - 4.4.

In the absence of the ability to determine INR, monitoring by prothrombin time (PT) is acceptable, but this method is much less reliable. No other blood tests are needed to calculate your warfarin dose. To identify the side effects of the drug, a general blood test, urine test and some biochemical tests are periodically prescribed.

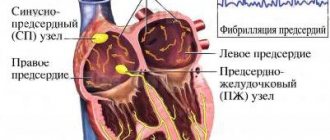

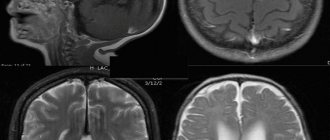

Current issues of warfarin therapy for practicing physicians

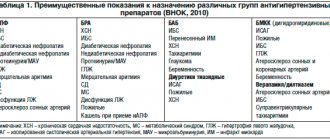

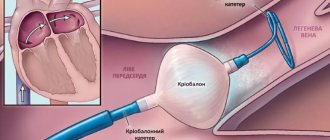

Currently, the effectiveness of Warfarin has been proven for the prevention of thromboembolic complications in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), after heart valve replacement, in the treatment and prevention of venous thrombosis, as well as in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular episodes in patients who have suffered acute coronary syndrome [1,2 ]. Use of Warfarin for atrial fibrillation The main cause of death and disability in patients with AF without damage to the heart valves is considered ischemic stroke (IS), which is cardioembolic in its mechanism [3–6]. The source of thrombotic masses is in most cases thrombosis of the left atrial appendage, less often - the cavity of the left atrium. Cardioembolic strokes in patients with AF are characterized by extensive cerebral infarction, leading to severe neurological deficits, which in most cases entails permanent disability of the patient [7]. According to large studies, the risk of stroke in patients with AF increases 6 times compared to those with sinus rhythm; it is comparable in paroxysmal and permanent forms of AF and does not depend on the success of antiarrhythmic therapy [3–6,8,9]. The reduction in the risk of IS during warfarin therapy in patients with AF without valvular heart disease has been proven by large randomized studies; it is 61% [10–14]. The determining factor in the choice of antithrombotic therapy tactics in each individual patient with AF is the presence of risk factors (RFs) for thromboembolic complications (TEC). The basis for stratifying a patient with AF is the CHADS2 score, first published in 2001 and retained as the initial risk assessment in the updated guidelines in 2011 [1]. Factors such as chronic heart failure (CHF), arterial hypertension (HTN), age ≥ 75 years and diabetes mellitus are scored 1 point, and IS/TIA or a history of systemic embolism – 2 points. The risk is assessed as high if there are 2 or more points. In 2009, a group of researchers from Birmingham led by G. Lip [15] proposed a new system for stratifying patients, which they called CHA2DS2–VASc. The basis was a 1-year follow-up of a cohort of 1577 patients with AF without heart valve disease who did not receive anticoagulant therapy. The CHA2DS2–VASc scale divides factors into “major” and “clinically associated minor.” “Major” includes previous IS/TIA/systemic embolism and age ≥ 75 years (estimated at 2 points), and “clinically associated minor” includes CHF or asymptomatic decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction ≤40%, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, age 65–74 years, female gender and vascular diseases (myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis of peripheral arteries, atherosclerosis of the aorta), scored 1 point. The fundamental changes are the assessment of female gender and vascular diseases as risk factors and the division of age into two gradations (Table 1). The CHADS2 scale is recommended for the initial determination of the risk of VTE in patients with MA. For patients with a CHADS2 score of ≥2, long-term VKA therapy is indicated under the control of an INR of 2.0–3.0, unless there are contraindications. For a more detailed and thorough risk calculation (in patients with a score of 0–1 on the CHADS2 scale), it is recommended to evaluate the presence of “large” and “clinically associated small” risk factors. Patients with 1 “major” or ≥2 “clinically associated small” risk factors are at high risk of TEC and are recommended to receive VKA therapy unless contraindicated. Patients who have 1 “clinically associated minor” risk factor have an average risk of TEC and are recommended to be treated with VKA or acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) at a dose of 75–325 mg per day. Patients who do not have RF or are at low risk may be prescribed ASA 75–325 mg, or they do not need any antithrombotic therapy. In addition to patients with chronic atrial fibrillation, anticoagulants are required for patients who are planning to restore sinus rhythm. The risk of systemic thromboembolism during cardioversion without the use of anticoagulants reaches 5%, and the use of 4-week warfarin therapy before and after cardioversion can reduce this risk to 0.5–0.8% [16–17]. All patients with a paroxysm of AF lasting 48 hours or more, or when the duration of the paroxysm cannot be determined, are indicated for VKA therapy with maintenance of an INR of 2.0–3.0 for three weeks before and four weeks after cardioversion, regardless of the method of restoring sinus rhythm (electrical or pharmacological). The exclusion of thrombosis of the appendage and cavity of the left atrium according to the emergency echocardiography data allows us to approximate the timing of cardioversion and restore sinus rhythm after achieving the target INR range of 2.0–3.0. However, in this case, the patient is advised to take Warfarin therapy for 4 weeks to exclude normalization thromboembolism. after cardioversion. When performing urgent cardioversion, heparin therapy (unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin) is indicated. If the AF paroxysm lasted 48 hours or more or when it is impossible to determine the duration of the paroxysm, after emergency cardioversion, VKA therapy is indicated for 4 weeks. If the duration of the paroxysm did not exceed 48 hours in a patient who does not have FR TEO, it is possible to perform cardioversion after the administration of heparin without the subsequent administration of Warfarin. In patients with risk factors for stroke or a high probability of recurrent AF, VKA therapy is indicated indefinitely, regardless of maintenance of sinus rhythm immediately after cardioversion. Approaches to anticoagulation therapy for cardioversion performed in connection with atrial flutter are similar to those used for atrial fibrillation [1–2]. Warfarin in patients with artificial heart valves The main danger to the life of patients with artificial heart valves is thromboembolic complications, the source of which are blood clots that form on the surface of the valve prosthesis. The risk of prosthetic valve thrombosis, a life-threatening complication, in the absence of VKA therapy reaches 8–22% per year [2,18]. Prescribing Warfarin reduces the risk of thromboembolism by 75%, therefore, when installing mechanical prosthetic heart valves, VKAs are mandatory and cannot be replaced by ASA. The exception is patients with bioprostheses without FR TEO, the duration of VKA therapy for whom is three months; in all other cases, treatment should be lifelong. Risk factors for patients with artificial heart valves are a history of thromboembolism, AF, circulatory failure, and atriomegaly. The level of anticoagulation in the vast majority of cases should be within the INR range of 2.5–3.5. The exception is patients after implantation of a modern bicuspid aortic valve prosthesis in the absence of other risk factors for thromboembolism, in this case the target INR range is 2.0–3.0 [2.18]. Indications for VKA therapy in patients after heart valve replacement are presented in Table 2. Warfarin in the treatment of venous thrombosis The duration of warfarin therapy in patients after deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PETA) associated with a reversible factor is 3 months. The duration of warfarin therapy in patients after unprovoked DVT/TEOLA is at least 3 months. In the future, it is necessary to evaluate the risk-benefit ratio of continuing VKA therapy. Long-term (lifelong) use of VKAs is recommended for patients who have experienced a first episode of unprovoked proximal DVT/TEOLA, have adequate INR monitoring, and do not have bleeding risk factors. Long-term VKA therapy is indicated for patients who have experienced a second episode of unprovoked venous thrombosis. The principles of treatment for asymptomatic and symptomatic venous thrombosis are similar. The level of anticoagulation for the prevention of recurrent venous thrombosis corresponds to an INR of 2.0–3.0 [2]. VKA in the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease The effectiveness of Warfarin in the secondary prevention of coronary artery disease was studied in the ASPECT-2, APRICOT-2, WARIS-II, CHAMP studies [19–22]. These studies differed in design, anticoagulation regimens, the presence of concomitant ASA therapy and the dose of the latter. The effectiveness of the combination of Warfarin and ASA was higher than ASA monotherapy, but the risk of hemorrhagic complications was higher in the combination therapy group. In this regard, in routine clinical practice, without special indications, Warfarin is not prescribed to patients with coronary artery disease. Practical aspects of VKA therapy Warfarin therapy should be selected based on a dose titration schedule to achieve target INR values. Before prescribing Warfarin, it is necessary to assess the presence of contraindications, the risk of bleeding in the patient, and also conduct an examination aimed at verifying potential sources of bleeding. Absolute contraindications to the use of Warfarin are an allergy to the drug, a history of hemorrhagic stroke, active bleeding, and significant thrombocytopenia. All other conditions are relative contraindications, and the choice is made based on the individual balance of benefit and risk of bleeding. Before prescribing Warfarin, it is necessary to clarify whether the patient has a history of hemorrhagic complications and to conduct an examination aimed at clarifying the status of potential sources of bleeding. The plan for mandatory and additional examination is presented in Figure 1. It is necessary to assess the risk of bleeding in all patients before prescribing antithrombotic therapy, taking into account the comparable risk of ASA and Warfarin, especially in elderly patients. In 2010, experts from the European Society of Cardiology introduced the HAS-BLED scale, which allows one to calculate the risk of bleeding in a patient. The risk is assessed as high if there are ≥3 points, however, this is not a contraindication for anticoagulant therapy, but regular monitoring is required during VKA or ASA therapy (Table 3). As a starting dose of Warfarin, it is advisable to use 5–7.5 mg during the first two days with further titration of the dose, focusing on the achieved INR level (Fig. 2). Lower starting doses of Warfarin (5 mg or less) are recommended for patients over 70 years of age, with low body weight, CHF or renal failure, as well as for patients with underlying liver dysfunction, concomitant use of amiodarone, and patients who have recently undergone surgery. The American recommendations of 2012 [2] indicate the starting dose of Warfarin (10 mg), however, taking into account the difference between the American population and the Russian population, as well as the increased risk of bleeding during the saturation period, it is advisable not to exceed the initial starting dose 7. 5 mg. In addition, immediately prescribing high starting doses of Warfarin (10 mg or more) is not recommended, as this leads to a decrease in the level of the natural anticoagulant protein C, which can lead to the development of venous thrombosis. During dose selection, INR monitoring is carried out once every 2–3 days. After receiving the INR results within the target range, the dose of Warfarin twice is considered selected, and in the future, INR monitoring is carried out once a month. The target INR range for patients with AF without heart valve damage and after venous thrombosis when using Warfarin without antiplatelet agents is 2.0–3.0, when combined with antiplatelet agents – 2.0–2.5. In patients after implantation of artificial heart valves, in most cases the target INR is 2.5–3.5. Currently, polymorphisms have been identified in the main biotransformation gene of Warfarin - CYP2C9 and the target molecule of its action - VKORC1. Carriers of mutant alleles require a lower maintenance dose of Warfarin, while the frequency of bleeding and episodes of excessive hypocoagulation is higher. Currently, there are algorithms for calculating the dose of Warfarin based on genotyping [23–28], the implementation of which is quite possible both from the point of view of routine practice and from an economic point of view. However, the recommendations [1–2] state that in the current absence of data from specific randomized trials, the use of a pharmacogenetic approach to VKA prescription for all patients is not recommended. Warfarin is a drug that is characterized by interindividual differences in drug response due to a number of factors, both external (diet, drug interactions) and internal (the patient's physical condition, age), as well as genetically determined. To exclude unwanted drug interactions when prescribing concomitant therapy, preference should be given to drugs whose effect on the anticoagulant effect of Warfarin is insignificant (Fig. 3). The use of drugs that affect the metabolism of VKA requires monitoring the INR after 3–5 days and, if necessary, adjusting the dose of Warfarin. Patients taking anticoagulants require a patronage system, which is due to the need for regular monitoring of INR, drug dose adjustment and assessment of other factors affecting INR values. It is advisable to give the patient a reminder. Fluctuations in INR values can be caused by several factors: 1. Laboratory error. 2. Significant changes in dietary vitamin K intake. 3. The influence of changes in somatic status, taking medications, alcohol and substances of plant origin on the metabolism of Warfarin. 4. Lack of adherence to treatment with Warfarin. To exclude food interactions, patients taking Warfarin should be advised to adhere to the same diet, limit alcohol consumption, and not take medications and herbal substances on their own without consulting a doctor, taking into account the possibility of their influence on the metabolism of Warfarin. INR values from measurement to measurement in the same patient may vary within the therapeutic range. Fluctuations in INR that are slightly outside the therapeutic range (1.9–3.2) are not grounds for changing the dose of the drug. It is necessary to monitor the INR value after 1 week, after which, if necessary, adjust the dose of Warfarin. To avoid significant fluctuations in the level of anticoagulation, it is advisable to reduce the dosage of Warfarin at INR values of more than 3.0 but less than 4.0, without skipping the next dose of the drug. There is no average daily dose of Warfarin. The dose should be adjusted based on the target range. The question of what is considered true resistance to Warfarin remains open to this day. It may be worth talking about true resistance if the prescription of a dose of Warfarin exceeding 20 mg per day did not lead to the achievement of a therapeutic level of anticoagulation. This is the so-called “pharmacodynamic (or true) resistance”, which can be confirmed by identifying a high concentration of Warfarin in the blood plasma in the absence of an increase in INR values. The number of such cases among patients, according to specialized studies, does not exceed 1% [27,28]. Risk of bleeding during VKA therapy The development of hemorrhagic complications is the most dangerous side effect of VKA therapy and the main reason for non-prescription of drugs in this group. The incidence of major bleeding during warfarin therapy is about 2%, and fatal bleeding is about 0.1% per year [3–7,29–32]. Non-hemorrhagic side effects of Warfarin are very rare - allergic reactions (itching, rash), gastrointestinal disorders (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain), transient baldness. The main risk factors for hemorrhagic complications are the degree of hypocoagulation, advanced age, interactions with other drugs and invasive interventions, and initiation of therapy [29–32]. To improve the safety of therapy, it is necessary to identify contraindications and potential sources of bleeding, take into account concomitant pathology (CHF, chronic renal failure, liver failure, postoperative period) and therapy. The occurrence of major bleeding (i.e., leading to death, cardiac/respiratory problems, other irreversible consequences, requiring surgical treatment or blood transfusion) always requires urgent hospitalization of the patient to find its cause and quickly stop it. Resumption of warfarin therapy after major bleeding is possible only if the cause of the bleeding is found and eliminated. The target INR range should be reduced to 2.0–2.5. The occurrence of minor hemorrhagic complications (any internal or external bleeding that does not require hospitalization, additional examination and treatment) requires temporary discontinuation of Warfarin until the bleeding stops, a search for its possible cause and dose adjustment of Warfarin. If minor bleeding occurs against the background of an INR value > 4.0, it is necessary to find out the possible reasons for the development of excessive hypocoagulation (primarily taking medications that affect the metabolism of VKA). Warfarin therapy can be resumed after stopping minor bleeding if the INR is <3.0. In case of recurrence of small hemorrhages, the target INR level should be reduced to 2.0–2.5. Excessive anticoagulation is a predictor of bleeding, so any, even asymptomatic, increase in INR levels above the therapeutic range requires the attention of a doctor. It is necessary to clarify with the patient the possible reasons for the increase in INR (primarily drug interactions, as well as such reasons for the development of excessive hypocoagulation as CHF, liver failure, hyperthyroidism, alcohol consumption). Detection of an asymptomatic increase in INR in a patient in the absence of any immediate need for invasive intervention requires temporary withdrawal of Warfarin with subsequent adjustment of its dose, but there is no need to administer fresh frozen plasma or prothrombin complex concentrate. Vitamin K promotes de novo synthesis of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors due to its influence on carboxylation processes, so the effect after its intake occurs slowly and it is useless for the rapid restoration of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors. The domestic drug phytomenadione available to doctors in capsules of 0.1 g, containing a 10% solution of vitamin K1 in oil, cannot be used to reduce the level of INR, since a dose of vitamin K equal to 10 mg causes resistance to the action of VKA for 7–10 days. The risk of bleeding increases during invasive interventions and surgical operations. The basis for correctly selected perioperative tactics in a patient taking Warfarin is an assessment of the risk of bleeding and thromboembolic complications (Fig. 4). In 2010, ESC guidelines [1] recommend early resumption of anticoagulant therapy in patients at high risk of thromboembolic complications, provided there is adequate hemostasis. ESC experts also published an addition to the existing recommendations [33] that there is no need to discontinue warfarin in patients at high risk of stroke during dental extraction, cataract removal and endoscopic removal of polyps from the gastrointestinal tract, provided that modern technology is used and adequate hemostasis is ensured. In this case, in the author’s own opinion, it is advisable to skip taking Warfarin on the eve of the intervention, provided that adequate hemostasis is maintained. Currently, there are portable devices for measuring INR levels. A meta-analysis conducted by S. Heneghan in 2006 [34] showed that self-monitoring of INR improves the outcomes of patients receiving warfarin. However, a necessary condition for adequate self-monitoring using a portable device is medical supervision for the correct interpretation of the results of the analysis and correction of factors that influence anticoagulant therapy. Conclusion Currently, Warfarin is the main drug for the prevention of thromboembolic complications in patients with myocardial infarction after heart valve replacement and venous thrombosis. The determining factor in the effectiveness of therapy with vitamin K antagonists is the target INR range, which should be attempted in every patient. The frequency of hemorrhagic complications, as well as the need for constant laboratory monitoring, are the main reasons for non-prescription or discontinuation of Warfarin in real clinical practice. The emergence of new antithrombotic drugs that do not require regular laboratory monitoring also requires doctors to acquire practical clinical experience. Existing algorithms for selecting an individual maintenance dose of Warfarin, a system of patronage and regular laboratory monitoring of INR can improve the safety of anticoagulant therapy.

Literature 1. Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation 2011. The task force for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation of European Society of Cardiology. 2. ACCP American college of Chest Physicians Evidence–Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (9th Edition) // Chest. – 2012. in press. 3. Wolf PA, Dawber TR, Thomas E. Jr et al. Epidimiologic assessment of chronic atrial fibrillation and risk of stroke: The Framingham Study // Neurol. – 1978. – Vol. 28. – P. 973–977. 4. Onundarson PT, Thorgeirsson G., Jonmundsson E. et al. Chronic atrial fibrillation – Epidimiologic features and 14 year follow-up: A case control study // Eur. Heart. J. – 1987.– Vol. 3. – P.521–27. 5. Flegel KM, Shipley MJ, Rose G. Risk of stroke in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation // Lancet. – 1987.– Vol. 1.– P.526–529. 6. Tanaka H., Hayashi M., Date C. et al. Epidemiologic studies of stroke in Shibata, a Japanese provincial city: Preliminary report on risk factors for cerebral infarction // Stroke. – 1985. – Vol. 16.– P. 773–780. 7. Hylek MPH, Alan S. Go, Yuchiao Chang et al. Effect of Intensity of Oral Anticoagulation on Stroke Severity and Mortality in Atrial Fibrillation // NEJM. – 2003. –Vol. 349. – P.1019–1026. 8. Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP et al. The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Investigators. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation // NEJM. – 2002. – Vol. 347. – P.1825–1833. 9. Stefan H. Hohnloser, Karl–Heinz Kuck, Jurgen Lilienthal. For the PIAF Investigators Rhythm or rate control in atrial fibrillation—Pharmacological Intervention in Atrial Fibrillation (PIAF): a randomized trial // Lancet. – 2000. – Vol. 356. –P. 1789 – 1794. 10. Petersen P., Boysen G., Godtfredsen J. et al. Placebo–controlled, randomized trial of warfarin and aspirin for prevention of thromboembolic complications in chronic atrial fibrillation. The Copenhagen AFASAK study // Lancet. – 1989. – Vol. 28;1(8631). – P.175–179. 11. Secondary prevention in nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation and transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. EAFT (European Atrial Fibrillation Trial) Study Group // Lancet. – 1993. – Vol. 342. – P. 1255–1262. 12. Hart RG, Pearce LA, McBride R. et al. Factors associated with ischemic stroke during aspirin therapy in atrial fibrillation: analysis of 2012 participants in the SPAF I–III clinical trials. The Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation (SPAF) Investigators // Stroke. – 1999. –Vol. 30(6). – P.1223–1229. The effect of low-dose warfarin on the risk of stroke in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. 13. The Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for Atrial Fibrillation Investigators // NEJM. – 1990. – Vol. 323. – P.1505–1511. 14. Ezekowitz MD, Bridgers SL, Javes KE et al. Warfarin in the prevention of stroke associated with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation // NEJM. – 1992. – Vol. 327, No. 20. – P. 1406–1413. 15. Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R., Pisters R. et al. Refining Clinical Risk Stratification for Predicting Stroke and Thromboembolism in Atrial Fibrillation Using a Novel Risk Factor–Based Approach The Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation // Chest. – 2010.– Vol. 137. – P. 263–272. 16. Arnold AZ, Mick MJ, Mazurek RP Role of prophylactic anti-coagulation for direct cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter // J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.– 1992.– Vol. 19.– P. 851–855. 17. Manning WJ, Silverman DI, Keighley CS et al. Transesophageal echocardiographically facilitated early cardioversion from atrial fibrillation using short term anticoagulation: final results of a prospective 4.5–year study // J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. – 1995. – Vol. 25(6). – P.1354–1361. 18. Dzemeshkevich S.L, Panchenko E.P. Anticoagulant therapy in patients with valvular heart disease // RMZh. – 2001. – T. 9, No. 10. – P. 427–430. 19. Anticoagulants in the Secondary Prevention of Events in Coronary Thrombosis (ASPECT) Research Group. Effect of long-term oral anticoagulant treatment on mortality cardiovascular morbidity after myocardial infarction // Lancet. – 1994.– Vol. 343. – P. 499–503. 20. Brouwer MA, van den Bergh PJ, Aengevaeren WR et al. Aspirin plus coumarin vs aspirin alone in the prevention of reocclusion after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction: results of the Antithrombotics in the Prevention of Reocclusion in Coronary Thrombolysis (APRICOT)–2 Trial // Circulation. – 2002. – Vol.106. – P.659–665. 21. Hurlen M., Smith P., Arnesen H. et al. Warfarin–Aspirin Reinfarction Study II WARIS –II // NEJM. – 2002. – Vol. 347. – P.969–974. 22. Fiore LD, Ezekowitz MD, Brophy MT et al. For the Combination Hemotherapy and Mortality Prevention (CHAMP) Study Group Warfarin combined with low dose aspirin in myocardial infarction did not provide clinical benefit beyond that of aspirin alone // Circulation. – 2002. – Vol.105. – P. 557–563. 23. Holbrook AM, Jennifer A. Pereira, Renee Labiris et al. Systematic Overview of Warfarin and Its Drugand Food Interactions // Arch. Intern. Med. – 2005. – Vol. 165. – P. 1095–1106. 24. Rieder MJ, Reiner AP, Gage BF et al. Effect of VKORC1 haplotypes on transcriptional regulation and warfarin dose // NEJM. – 2005. –Vol. 352(22). – P.2285–2293. 25. Higashi MK, Veenstra DL, Kondo LM et al. Association between CYP2C9 genetic variants and anticoagulation–related outcomes during warfarin therapy // JAMA. – 2002. –Vol. 287. – P.1690–1698. 26. Tabrizi AR, Zehnbauer BA, Borecki IB et al. The frequency and effects of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C9 polymorphisms in patients receiving warfarin // J. Am. Coll. Surg. – 2002. – Vol. 194. – P.267–273. 27. Harrington DJ, Underwood S, Morse C et al. Pharmacodynamic resistance to warfarin associated with a Val66Met substitution in vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 // Thromb. Haemost. – 2005. – Vol. 93. – P. 23–26. 28. Bodin L., Horellou MH, Flaujac C. et al. A vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit–1 (VKORC1) mutation in a patient with vitamin K antagonist resistance // J. Thromb. Haemost. –2005. – Vol. 3. – P.1533–1535. 29. Fihn SD, McDommel M, Matin D et al. Risk factors for complications of chronic anticoagulation. A multicenter study. Warfarin Optimized Outpatient Follow-up Study Group // Ann. Intern. Med. – 1993. – Vol. 118(7). – P. 511–520. 30. Mhairi Copland, Walker ID, Campbell R. et al. Oral Anticoagulation and Hemorrhagic Complications in an Elderly Population With Atrial Fibrillation // Arch. Intern. Med. – 2001. – Vol. 161, No. 17. – P. 24. 31. Levine MN, Raskob G., Landefeld S., Kearon C. Hemorrhagic complication of anticoagulant treatment // Chest. – 2001. – Vol. 19(1 Suppl). – P.108S–121S. 32. Palareti G., Leali N., Cocceri S., Poggi M. et al. Hemorrhagic complications of oral anticoagulant therapy: results of a prospective multicenter study ISCOAT (Italian Study on Complications of Oral Anticoagulant Therapy) // G. Ital. Cardiol. – 1997. – Vol. 27(3).– P.231–243. 33. Skolarus LE, Morgenstern LB, Froehlich JB et al. Guidline–Discordant Perioprocedural Interruption in warfarin therapy // Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. – 2011. –Vol. 4. 34. Heneghan C., Alonso–Coello P., Garcia–Alamino JM et al. Self-monitoring of oral anticoagulation: a systematic review and meta-analysis // Lancet. – 2006. – Vol. 367. – P. 404–411.

How to take the drug

Warfarin is available in 2.5 milligram tablets. Most often, the “starting” and “maintenance” doses of the drug are 5 milligrams (2 tablets) per day. In many cases, for more “fine” adjustments, you will change the dose of the medicine that you take not per day, but per week. This may require either dividing the tablet in half or taking different numbers of tablets on different days. To make it easier to monitor your treatment, you may be given a special account book, or you can keep a notebook with a treatment diary, where it is useful to note the doses of warfarin, INR level, and other laboratory data.

Warfarin is taken in the entire daily dose at one time, preferably at 17:00 - 19:00. Take the tablets with water. It is not recommended to take it with food, but can be taken on an empty stomach. Phenyline is usually taken in 2 doses.

Warfarin or Phenilin

, Ukraine

Release form: tablets

Active ingredient: Phenindione

Warfarin analog Phenilin is an indirect anticoagulant that blocks the enzyme K-vitamin reductase. It is used for the treatment and prevention of thrombosis and embolism, for prosthetic heart valves.

Doses are selected based on laboratory tests.

The disadvantage of the Phenilin analogue is the requirement for constant monitoring of not only prothrombin time and INR, but also regular analysis of coagulograms, thromboelastograms and platelet counts.

Warfarin dose selection

The most difficult and responsible stage. “Loading” initial doses of warfarin (more than 5 mg) are not recommended.

Dose selection can be carried out both with and without the use of low molecular weight heparins (Fraxiparine, Clexane), both in the hospital and on an outpatient basis. The selection period on average takes from 1 to 2 weeks, but in some cases it increases to 2 months. At this time, you will need frequent INR determinations, up to 2 - 3 times a week or daily. Each time, after receiving the next test result, your doctor will determine a change in the dose of the medication and the date of the next test.

If in several tests in a row the INR remains in the range of 2.0 - 2.5, this means that the dose of warfarin has been adjusted. Further monitoring of treatment will be much easier.

Warfarin or Thrombo ACC – which is better?

Manufacturer: Lannacher, Austria

Release form: film-coated tablets

Active ingredient: Acetylsalicylic acid

Synonyms: Aspirin Cardio, Thrombopol, CardiASK

To thin the blood, Warfarin can be replaced with the Austrian drug Trombo ACC, which contains acetylsalicylic acid in 50 and 100 mg doses. In these tiny doses it has antiplatelet properties.

An analogue of Thrombo ACC can be freely purchased without a doctor’s prescription and taken 1 tablet daily for the prevention of heart attack, stroke, and other diseases accompanied by increased thrombus formation.

An analogue of Thrombo ACC is also prescribed after vascular surgery.

To prevent the negative effects of acid on the stomach, Trombo ACC tablets are coated with a special enteric coating. Therefore, they should not be chewed or divided in half.

Monitoring the dose of warfarin

If the dose of the drug is selected, less frequent monitoring is sufficient - first once every 2 weeks, then once a month. The frequency of additional studies is determined separately. The need for an extraordinary determination of the INR may arise in a number of cases, which we will discuss below. If in any doubt, ask your doctor for advice.

Currently, there are portable devices for self-determination of INR (similar to systems for monitoring blood sugar levels in patients with diabetes), but their cost is very high and, in most cases of deep vein thrombosis, purchasing them is impractical.

What may affect treatment

- Any concomitant diseases (including “colds” or exacerbation of chronic diseases)

- The use of drugs that affect the blood coagulation system. This is especially true for a large class of drugs that includes aspirin. It also includes many drugs prescribed as anti-inflammatory and painkillers (diclofenac, ibuprofen, ketoprofen, etc.). As a mild analgesic during treatment with warfarin, it is better to use paracetamol in normal dosages. In any case, the need for a new medication and the duration of its use must be agreed with the attending physician. When warfarin and aspirin are prescribed simultaneously, the INR is maintained in the range of 2.0 - 2.5.

- The use of drugs that affect the absorption, excretion and metabolism of warfarin. Most often, it is necessary to take into account the prescription of broad-spectrum antibiotics and oral antidiabetic agents. However, taking any new medicine may change how warfarin works. If concomitant treatment is necessary, additional INR analysis is usually prescribed at the beginning and end of therapy.

- Diet changes.

Warfarin acts on blood clotting through vitamin K, which is found in varying amounts in food.

There is no need to avoid foods high in vitamin K! Nutrition should be complete. You just need to make sure that there is no significant change in their proportion in the diet, for example, depending on the season. If you significantly increase your intake of foods rich in vitamin K while on a stable dose of warfarin, this may greatly weaken its effect and lead to thromboembolic complications.

The maximum amount of vitamin K (3000 - 6000 mcg/kg) is found in dark green leafy vegetables and herbs (spinach, parsley, green cabbage), and in green tea up to 7000 mcg/kg; intermediate amounts (1000 - 2000 mcg/kg) - in plants with paler leaves (white cabbage, lettuce, broccoli, Brussels sprouts). A significant amount of the vitamin is found in legumes, mayonnaise (due to vegetable oils), and green tea. Fats and oils contain varying amounts of vitamin K (300 - 1000 mcg/kg), more of it in soybean, rapeseed, and olive oils. The content of vitamin K in dairy, meat, bakery products, mushrooms, vegetables and fruits, black tea, coffee is low (no more than 100 mcg/kg). Regular consumption of berries and cranberry juice may increase the effect of warfarin.

Small doses of alcohol with normal liver function do not affect anticoagulant therapy, but alcohol consumption must be treated with caution.

Taking multivitamins that contain vitamin K may reduce the effect of warfarin.

Answers on questions

How to replace Warfarin for atrial fibrillation

With atrial fibrillation or atrial fibrillation, the risk of blood clots increases; to prevent this phenomenon, Warfarin analogues and substitutes are prescribed - direct or indirect anticoagulants.

When is it better to take Warfarin - morning or evening?

The time of day does not matter when taking Warfarin. It is important to take regularly, at the same time.

Warfarin - direct or indirect anticoagulant

The drug belongs to the group of indirect anticoagulants, since it does not act directly on thrombin, but as a vitamin K antagonist.

It is important

Always tell any health care professional you see that you are taking anticoagulants. It is advisable to carry your “account” book or treatment diary with you.

Most dental procedures (except tooth extraction) can be performed without changing your treatment regimen. When removing a tooth, it is usually sufficient to use a tampon with a local hemostatic agent (aminocaproic acid, thrombin sponge).

If you have problems with blood pressure, you need to regularly monitor it and maintain it at a level not higher than 130/80 mmHg.

Warfarin and pregnancy

During pregnancy, taking warfarin is contraindicated. In the event of pregnancy, indirect anticoagulants are immediately discontinued; if further prevention of thrombosis is necessary, heparins are usually used. Therefore, if you suspect pregnancy, refrain from taking the drug until you consult your doctor.

It is possible to use warfarin during breastfeeding. Warfarin is excreted in breast milk in extremely small quantities and does not affect the baby's blood clotting processes, but for complete safety it is recommended to refrain from breastfeeding during the first three days of the mother's treatment with the drug.

pharmachologic effect

Manufacturer: Ozone, Canon Pharma, Russia/Takeda, Denmark

Release form: tablets

Active ingredient: Warfarin

Synonyms: Warfarex, Warfarin Nycomed

Warfarin has an anticoagulant effect due to blocking the synthesis of blood coagulation factors dependent on vitamin K, reducing their content in the blood and slowing down coagulation.

The onset of action usually occurs on the second day of administration, the maximum effect occurs after about a week. After discontinuation of the vitamin-K medication, dependent factors are restored on average within five days.