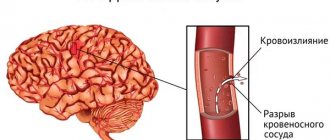

Hemorrhagic stroke (HI) is a clinical syndrome in which there is a sharp development of focal and/or cerebral neurological symptoms due to spontaneous hemorrhage into the substance of the brain or into intrathecal areas. The pathological process is triggered by factors of non-traumatic genesis. This type of hemorrhage has the highest disabling ability and is associated with the highest risk of early death.

Statistics facts from reliable sources

In the general structure of all types of strokes, hemorrhagic strokes account for 10%-15%. The frequency of its spread among the world population is about 20 cases per 100 thousand people. Experts, based on annual dynamics, report that in about 50 years all these indicators will double. Specifically in the Russian Federation, about 43,000-44,000 cases of HI are diagnosed annually. What is noteworthy is that it occurs approximately 1.5 times more often in men, but the mortality rate from its consequences predominates in women.

According to clinical observations, with this diagnosis, death occurs in 75% of people who are on mechanical ventilation, and in 25% of people who do not need it. Consolidated studies have shown that on average 30%-50% of patients die within 1 month from the moment of an attack of hemorrhage, and 1/2 of them die within the first 2 days. Disability (due to paralysis of the face and limbs, aphasia, blindness, etc.) among surviving patients reaches 75%, of which 10% remain bedridden. And only 25% of patients are independent in everyday life after 6 months.

Pathology represents a huge social problem, since the epidemiological peak occurs in working years - 40-60 years. Hemorrhagic strokes have become significantly “younger”; today they are quite common even among the youth group of people (20-30 years old). The risk category definitely includes people suffering from arterial hypertension, since in most cases this kind of hemorrhage occurs precisely because of chronically elevated blood pressure.

The primary factor that influences the prognosis of outcome is the promptness of providing adequate medical care to the patient.

Myocardial infarction and hemorrhagic alveolitis in systemic lupus erythematosus

Despite the well-known symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), each case of this disease is unique. The course of the disease is characterized by periods of exacerbations and remissions that occur while taking medications. Discontinuation of treatment is usually accompanied by exacerbation of SLE at varying intervals. The disease can begin with damage to one or more organs or progress at lightning speed, ending in death in a short period of time.

The main causes of death during the first year after the onset of the disease are the activity of SLE (damage to the kidneys, central nervous system - CNS) or the addition of an infection. Subsequent deaths may be caused by cardiovascular accidents, chronic renal failure and malignant neoplasms [1]. The use of glucocorticosteroids can reduce the incidence of deaths resulting from SLE activity.

We describe a patient with SLE in whom disease activity caused the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation (thrombohemorrhagic stage) and death in the first year after the onset of SLE.

Patient K., 18 years old, was admitted to the hospital of the Institute of Rheumatology of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences in October 2003 with complaints of hemorrhagic rashes on the skin, pain in the right elbow, wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints of the right hand, swelling of these joints, hair loss, weakness, shortness of breath with physical activity.

The onset of the disease at the end of December 2002 was characterized by the appearance of erythema on the face, the development of arthritis of the small joints of the hands, low-grade fever, and a sharp decrease in body weight (in 2 months, I lost 6 kg). In January 2003, she was hospitalized in the rheumatology department of one of the hospitals in Moscow, where changes in urinary sediment (proteinuria, erythrocyturia and leukocyturia), anemia, increased antibodies to DNA and antinuclear factor (ANF, titers unknown) were detected, which allowed diagnose SLE. From the moment of diagnosis, she constantly received prednisolone (PZ - 35 mg/day), and after consultation at the Institute of Rheumatology (April 2003) also Plaquenil (400 mg/day). Despite the therapy, changes in urine tests (trace proteinuria and microhematuria) and immunological disorders persisted, and therefore cyclophosphamide - CP (total 1.2 g) was prescribed. Stop injections of CP and reduce the dose of PZ to 20 mg/day. provoked an exacerbation of SLE: in September 2003, a hemorrhagic rash appeared on the skin of the legs, and then throughout the body, painful aphthae in the mouth, arthritis and arthralgia recurred again, fever, and weakness began to increase. An episode of severe abdominal pain, nausea, and tarry stools occurred on September 30, and a decrease in hemoglobin to 81 g/l was noted. At the place of residence, the development of food toxic infection was excluded, rehydration therapy was carried out, after which the patient was sent to the Institute of Rheumatology. A brief history diagram is presented in Fig. 1.

Provocateurs of hemorrhagic stroke

The trigger for the appearance of HI can be quite a variety of factors that have a negative impact on intracranial hemodynamics and the condition of the cerebral vessels:

- persistent arterial hypertension (in 50% of cases);

- cerebral amyloid angiopathy (12%);

- oral administration of drugs from the anticoagulant spectrum (10%);

- intracranial neoplasms (8%);

- other causes are arteriovenous and cavernous malformations, thrombosis of the cerebral sinuses, aneurysms, vasculitis of intracranial vessels, etc. (20%).

Many of the patients with a history of hemorrhagic stroke have diabetes mellitus. It is a proven fact that diabetics, like hypertensive patients, are at risk. In long-term diabetes mellitus, blood vessels, including cerebral ones, are destroyed due to modification of blood chemistry with a predominance of glucose. If, against the background of elevated blood sugar, there is a tendency to constant increases in blood pressure, the likelihood of a hemorrhagic stroke increases by 2.5 times.

Pathogenetically, a hemorrhagic effect can develop as a result of rupture of a vessel (the predominant mechanism) or the leakage of blood elements into the surrounding brain tissue through the walls of capillaries due to their impaired tone and permeability. In the second option, there is no rupture and, as such, profuse hemorrhage. Just a small vessel allows blood to pass through pointwise. But even small-point hemorrhages, merging, can turn into very extensive foci, with no less fatal consequences than after a rupture of an artery or vein.

Clinical manifestations of HI

Shortly before the attack, pre-stroke clinical symptoms may precede the attack (not always), by which one can suspect impending danger:

- tingling, numbness of one facial half;

- numbness in fingers or toes;

- sudden weakness, dizziness, noise in the head;

- severe pain in the eyes, spots, double vision, vision in red;

- sudden staggering when walking;

- causeless tachycardia;

- attacks of hyperhidrosis;

- increased blood pressure;

- unreasonable occurrence of nausea;

- inhibition in communication and perception of other people's speech;

- flushing of the face, hyperthermia.

A cerebral stroke with hemorrhage is still characterized by an immediate acute onset without warning signs, which occurs during or almost immediately after vigorous activity, a stressful situation, or excitement. A hemorrhagic stroke is indicated by classic symptoms that develop suddenly, are pronounced and rapidly progress:

- sharp and severe headache;

- uncontrollable vomiting;

- prolonged depression of consciousness, coma;

- blood pressure above 220 mmHg.

Common signs of shock are also noisy breathing, epileptic seizures, lack of pupillary response to light, and spastic miosis. Depending on the location of the lesion, there may be a rotation of the head and rotation of the eyeballs in the direction of the affected hemisphere or contralaterally. Having discovered signs of GI in a victim, a person nearby must immediately call an ambulance!

Acutely developed hemorrhage leads to the fact that blood flows freely into certain structures of the brain, saturating them and forming a cavity with a hematoma. The bleeding continues for several minutes or hours until a blood clot forms. Over a short period of time, the hematoma quickly increases, exerting a mechanical effect on the affected areas. It stretches, presses and displaces the nervous tissue, causing its swelling and death, which leads to an intensive increase in neurological deficit (respiratory depression, loss of sensitivity of one half of the body, speech disorders, loss of vision, paresis of the swallowing muscles, etc.).

The size of the blood accumulation can be small (up to 30 ml), medium (from 30 to 60 ml) and large (more than 60 ml). The volumes of spilled liquid can reach critical levels, up to 100 ml. Clinical observations show that with intracranial hemorrhages exceeding 60 ml, the pathology ends in death in 85% of patients within 30 days.

Hemorrhagic stroke: rehabilitation and treatment

Motor recovery

Rehabilitation of motor function also begins at the stage of inpatient treatment, after the provision of primary medical care.

The limbs are moved to improve blood circulation in them. This helps reduce tone, prevent congestion and pneumonia. The position of the patient's limbs can be corrected using a splint or special weights. It is customary to turn bedridden people over every 2 hours so that they do not develop bedsores. Already in the first days after an attack, you can do passive gymnastics, in which a relative or health worker helps the person move his limbs smoothly. Such procedures are recommended only if the patient does not experience pain during the process. Then, as the condition improves, the patient is allowed to first sit in bed and then try to get up. Before starting to walk, a person trains to change the emphasis from foot to foot, regaining the sense of his position in space. Then the patient learns to move with the help of various supports, walkers, and canes.

Movement restoration techniques

Physical therapy plays a major role in the rehabilitation of motor function: exercises for various muscle groups are developed for the patient, training on special simulators, and the use of devices to reduce tone are recommended.

Therapeutic massage is very useful. At the first stage, stroking the limbs with increased tone and rubbing muscles with decreased tone are used. To improve the effect, you can use a warm heating pad before the session. The massage can last from 5 to 20 minutes, depending on the patient's condition.

Among the methods of physiotherapy, oxygen baths, electrophoresis of neck vessels, and electrical stimulation of weakened muscles have proven themselves well.

Speech restoration

Work on returning the patient’s speech can begin even if more than a year has passed since the attack. You need to speak with patients after a stroke slowly, pronouncing words clearly, do not rush to answer, and ask questions that require monosyllabic answers.

It is recommended to work with a speech therapist who will help restore the functionality of the facial and oral muscles; exercises in front of a mirror may be useful. Gradually, as improvements occur, you can complicate the tasks and encourage the person to construct more complex phrases.

Restoration of breathing, swallowing

After a patient is admitted to the hospital, he is usually fed with a tube, then he most often has to learn the skill of independent feeding again. To simplify rehabilitation, you need to properly prepare food for a stroke victim. The food should be warm and not too hard or soft in consistency. It is important to choose aromatic dishes, they promote the production of saliva.

Patients should not be rushed while eating; food usually takes them at least half an hour. It is important to help them hold the utensil or spoon and motivate them. The strength of the swallowing muscles is restored with regular repetition of the feeding process.

Psychological recovery

Many patients after a hemorrhagic stroke experience depression and cognitive impairment. Medicinal therapy, courses of nootropics and neurometabolic drugs help restore thinking.

To correct the psychological state, it is recommended to work with a psychologist. Sessions of group and individual psychotherapy have proven themselves well. The support of the patient’s relatives and friends is of great importance, which can restore a person’s confidence in his own relevance and fortitude.

Kulikova Anna Aleksandrovna, neurologist

Typical location of hemorrhages

Most often, and this is about 55% of cases, hemorrhages occur in the putamental zone. Putamental bleeding occurs due to rupture of degenerated lenticulostriate arteries, which causes blood to enter the brain shell. The culprit of pathogenesis with such localization is usually long-standing hypertension. In some cases, bleeding from the putamentum breaks into the ventricular system, which is fraught with tamponade of the gastrointestinal tract and acute occlusive-hydrocephalic crisis.

The next most common location is the subcortical region (subcortical). Subcortical GIs are observed in 17%-18% of cases. As a rule, the leading sources of such hemorrhage are ruptured AVMs and aneurysms against the background of increased pressure. The subcortical zones involved in the hemorrhagic process are the frontal, parietal, occipital or temporal lobe.

The third most common place, where brain hemorrhage is determined in 14%-15% of cases, is the optic thalamus, or thalamus. Thalamic hemorrhages occur due to the release of blood from the blood vessel of the vertebrobasilar region. Pathogenesis can be associated with any etiological factor, however, as always, the involvement of hypertensive syndrome is significantly more often noted.

In fourth place (7%) in terms of frequency of development are pontine GIs. They are concentrated in the back of the brain stem, that is, in the pons. Through the bridge, the cortex communicates with the cerebellum, spinal cord and other major elements of the central nervous system. This department includes the centers for controlling breathing and heartbeat. Therefore, the bridge is the most dangerous localization of hemorrhage, practically incomparable to life.

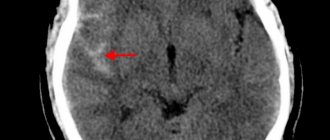

Principles of disease diagnosis

The gold standard for making a diagnosis is computed tomography (CT). In the early period after an attack (1-3 days), this method of neuroimaging is more informative than MRI. Fresh hemorrhagic material, including 98% hemoglobin, appears on CT as a high-density, well-defined, bright inclusion against the background of darker brain tissue. Based on a computed tomogram, the epicenter zone, volume and shape of the formation, the level of damage to the internal capsule, the degree of dislocation of brain structures, and the state of the cerebrospinal fluid system are determined.

With the onset of the subacute phase (after 3 days), the red cells of the hematoma along the periphery are destroyed, in the center the iron-containing protein is oxidized, and the focus becomes lower in density. Therefore, along with CT scan, MRI is mandatory within 3 days and later. In subacute and chronic forms, the MR signal, in contrast to CT, better visualizes a hematoma with derivatives of hemoglobin oxidation (methemoglobin), which passes into the isodense stage. Angiographic examination methods are used in patients with an unknown cause of hemorrhagic stroke. Angiography is primarily performed on young people with normal blood pressure readings.

For adequate management of patients after an attack of intracerebral hemorrhage, an ECG and X-ray of the respiratory organs are required, and tests for electrolytes, PTT and APTT are taken.

Medical care in hospital

All patients receive intensive therapeutic care at an early stage in a neuro intensive care hospital. Initial treatment measures are aimed at:

- normalization of microcirculation, hemorheological disorders;

- relief of cerebral edema, treatment of obstructive hydrocephalus;

- correction of blood pressure, body temperature;

- functional regulation of the cardiovascular system;

- maintaining water and electrolyte balance;

- prevention of possible seizures;

- prevention of extracranial consequences of inflammatory and trophic nature (pneumonia, embolism, pulmonary edema, pyelonephritis, cachexia, DIC syndrome, endocarditis, bedsores, muscle atrophy, etc.);

- providing respiratory support (if the patient needs it);

- elimination of intracranial hypertension in HI with dislocation.

Hemorrhagic pulmonary infarction

Content:

Hemorrhagic pulmonary infarction occurs due to embolism or thrombosis of the pulmonary arteries. As a result, an area of lung tissue with impaired blood circulation (ischemic zone) is formed.

The peculiarity of a hemorrhagic infarction is that in it the ischemic area is saturated with blood, has clear boundaries and is dark red in color. In appearance, such a heart attack resembles the shape of a cone, the base of which faces the pleura. Accordingly, the tip of the cone faces the root of the lung and a thrombus can be detected on it in one of the branches of the pulmonary artery.

Causes

Speaking about the causes of pulmonary infarction, we can highlight several main points leading to this condition.

- Peripheral vein thrombosis. Thrombosis of the deep femoral veins is especially common due to weak or slow blood circulation in them. At the same time, it is important to have an additional condition - a tendency to increased blood clotting in weakened patients who have been on bed rest for a long time.

- Inflammatory thrombophlebitis. This group also includes septic thrombophlebitis that occurs with a variety of general and local infections, after injury or surgery, with prolonged fever in the postoperative period, etc.

- Thrombosis in the heart and thromboendocarditis.

It is also worth highlighting the predisposing factors under which hemorrhagic pulmonary infarction develops somewhat more often. Here are the main ones:

- Myocardial infarction;

- Congestive heart failure;

- Obesity;

- Nephrotic syndrome;

- Operations in the lower abdominal cavity, as well as on the pelvic organs;

- Pregnancy;

- Prolonged immobility;

- Taking estrogens (oral contraceptives).

Clinic

Symptoms of a pulmonary infarction are usually pronounced and are quite difficult to miss. First, painful sensations appear in the armpit, in the area of the shoulder blade, or a feeling of tightness in the chest. The pain may worsen with coughing and breathing. Shortness of breath may also occur. At the same time, vascular reactions are observed - the skin becomes pale, sticky cold sweat appears. Breathing becomes frequent and shallow, and the pulse is weak. Also, with a massive heart attack, jaundice may be observed.

At the very beginning of a developing heart attack, the cough is dry, later it is accompanied by sputum with bloody discharge, and after some time the sputum becomes dark brown.

A blood examination reveals moderate leukocytosis.

When listening, the doctor detects pleural friction noise, muffled breathing and moist crepitating rales. There is also a shortening of the percussion sound.

There may be an accumulation of fluid in the pleural cavity, which manifests itself as dulling of percussion sound in the affected area, weakening of breathing, bulging of the intercostal spaces and vocal tremors.

To confirm the diagnosis and to prescribe the correct treatment for pulmonary infarction, a chest x-ray is required. With this disease, a wedge-shaped shadow will be noted in the lower or middle lobe of the lung (the right lung is most often affected).

Differential diagnosis

If a pulmonary infarction is suspected, the doctor often has to differentiate it from myocardial infarction. An ECG can help with this. But in some cases the resulting picture turns out to be similar. For example, an infarction of the posterior wall of the left ventricle may resemble symptoms of a pulmonary infarction. To make an accurate diagnosis in this case, more attention must be paid to collecting an anamnesis. In particular, recent surgery, thrombophlebitis, and mitral valve disease will indicate a possible pulmonary infarction. If there is a history of arterial hypertension and angina attacks, then there is a high probability of heart attack.

This condition should also be distinguished from lobar pneumonia, in which the first signs are fever and chills, and chest pain comes later. Lobar pneumonia is characterized by rust-colored sputum and a herpetic rash may occur.

Another similar condition is spontaneous pneumothorax. They are especially similar in the initial stages of development. A little later, these conditions differ in radiological and clinical signs.

A timely and correct diagnosis will help eliminate the serious consequences of a pulmonary infarction.

Treatment

Treatment of pulmonary infarction should be comprehensive and begin as early as possible.

First of all, it is necessary to relieve pain. For this purpose, analgesics can be used - both non-narcotic (intravenous administration of analgin solution) and narcotic (morphine solution). This will help not only reduce pain, but also relieve the pulmonary circulation.

If there is shortness of breath, oxygen therapy is indicated.

Separately, it is worth mentioning the prescription of anticoagulants. For successful treatment and to eliminate the consequences of pulmonary infarction, these drugs must be prescribed as early as possible. One such drug is heparin. Its intravenous administration will help stop the thrombotic process in the lung tissue.

With reduced pressure, rheopolyglucin can be prescribed (intravenous drip) to improve microcirculation. It is able to raise blood pressure and increase the volume of circulating blood.

The second step in the treatment of pulmonary infarction is measures aimed at preventing the development of infection. For this purpose, penicillins and sulfonamides can be prescribed.

Prevention

Considering the causes of pulmonary infarction, we can talk about preventive measures:

- Firstly, get up as early as possible after surgery. Even seriously ill patients are recommended to provide the necessary minimum of movements.

- Secondly, avoid unnecessary use of medications that increase blood clotting.

- If possible, limit intravenous drug administration.

- For thrombosis of the veins of the lower extremities, use a surgical method of vein ligation in order to avoid repeated embolisms.

Compliance with the above measures will help reduce the likelihood of developing venous thrombosis and the risk of developing a pulmonary infarction.

Heart attack

Infarction (Latin infarctus from infarcire to stuff, fill, squeeze in; synonyms discirculatory necrosis) is focal necrosis of an organ resulting from a sudden disruption of local circulation.

The term “infarction” was proposed by R. Virchow to refer to a dead area of tissue infiltrated (“infarcted”) by red blood cells.

The immediate cause of the development of a heart attack is an obstruction to blood flow that suddenly appears in the corresponding segment of the artery. It was assumed that a heart attack develops only in organs with so-called terminal arteries that do not have anastomoses. However, it was later established that anastomoses between the terminal branches of the arteries are present in all organs, although the degree of their severity varies. The small caliber of vessels, individual branching options and anomalies of their development, an insufficient number of vascular anastomoses characteristic of a given organ are prerequisites for the occurrence of a heart attack in conditions of general circulatory disorders. Only blockage of large main arteries can lead to necrosis of organ tissue without previous general hemodynamic disorders

When the lumen of the vessel is not completely closed, the cause of the development of a heart attack is a discrepancy between the nutritional needs of a functionally burdened organ and the insufficient blood supply to this area. Such a discrepancy can be observed, for example, in hypertension, heart defects and is caused not so much by the narrowing of blood vessels, but by their loss of elasticity and their inability to adapt to expansion. Ischemia (see full body of knowledge) of a certain area of an organ with minimal blood flow can also occur with a sharp drop in blood pressure. The development of a heart attack in this case is an indicator of general circulatory failure (cerebral, myocardial infarction). For the development of cardiac muscle infarction, the duration of ischemia, according to experimental data, is 20 minutes; for the formation of cerebral tissue infarction, 5-6 minutes are sufficient. Macroscopically and microscopically, tissue necrosis in the area of myocardial infarction is clearly detected on the 2nd day. At an earlier stage (the so-called pre-necrotic period), it is possible to identify microcirculation disorders, foci of contracture contraction of vascular myocytes or their lysis. Hypoxia plays a great role in the mechanism of development of tissue changes during a heart attack (see full body of knowledge). Disruption of redox processes in tissues due to circulatory disorders leads to the accumulation of under-oxidized metabolic products, which affect tissue colloids, vascular walls and lead to their necrosis (see full body of knowledge).

Of great importance in the development of a heart attack is the sudden narrowing or closure of the vascular lumen, therefore the most common cause of a heart attack is thrombosis (see full body of knowledge) and embolism (see full body of knowledge), less often spasm (see full body of knowledge). Under these conditions, collaterals are insufficient, dystonic phenomena easily occur, and blockage of the vessel leads to a heart attack.

Heart attacks are more common in the heart (see full body of knowledge), kidneys (see full body of knowledge), spleen (see full body of knowledge), lungs (see full body of knowledge), brain (see full body of knowledge), retina (see full body of knowledge knowledge), intestines (see full body of knowledge). Infarction in the kidneys, spleen, and lungs has a wedge-shaped shape, which is associated with their angioarchitecture (the main type of vessels heading from the hilum to the periphery) and affects the central part of the ischemic area; in this case, the tip of the wedge is directed towards the obstruction to blood flow (place of blockage or sharp narrowing of the vessel), and the wide part (base) is directed towards the periphery of the organ. In the heart muscle, the infarction has an irregular shape, capturing different zones of the myocardium layer by layer, starting from the subendocardial layers, which is due to the scattered type of branching of the vessels; in the intestine, the infarction is sharply demarcated, its extent depending on the caliber of the blocked artery.

Against the background of general and local circulatory disorders, small, sometimes microscopic, foci of necrosis—microinfarctions—typical of the myocardium and brain can occur in different organs. In their occurrence, a certain role can be played by pressure drops in small vessels, as well as a discrepancy between the increased need for tissue nutrition and insufficient blood flow under conditions of emotional or physical stress, as well as metabolic disorders caused by hypoxia or ischemia.

There are three types of heart attack: white (ischemic, anemic), red (hemorrhagic), white with a hemorrhagic belt.

White (ischemic) Infarctions are observed in the kidneys, spleen, brain, myocardium (color figure 1 and 3). They are triangular in shape, yellowish-white in color (hence the name “white”), quite sharply demarcated from the surrounding tissue, and have a dense consistency. They arise due to the complete cessation of blood flow in a given vessel and its branches. Necrosis in such cases always initially has the character of dry coagulation.

Red (hemorrhagic) Infarctions are observed in the lungs (color table, page 177, Figure 2), in the intestines, sometimes in the spleen and brain; arise, as a rule, in conditions of circulatory decompensation and venous stagnation: in the lungs - with heart failure of various origins, in the spleen - with thrombosis of its veins, in the brain - with thrombosis of the jugular veins or sinuses of the dura mater. In this case, there is a reverse flow of venous blood into the infarction zone, paralytic dilation of blood vessels, increasing their permeability and saturation of the infarction zone with blood. Hemorrhagic infarction is triangular in shape, dark red in color when cut, which determines its name, and is quite sharply demarcated from the surrounding tissue. Over time, the infarction becomes pale due to hemolysis of red blood cells.

White Infarction with a hemorrhagic belt - white or light gray with a dark red rim - is observed in the heart and spleen, sometimes in the kidneys. The hemorrhage zone occurs due to the fact that a reflex spasm along the periphery of the infarction is quickly replaced by paralytic expansion and overflow of blood in the capillaries with the development of the phenomena of prestasis, stasis (see full body of knowledge) and diapedetic hemorrhage (see full body of knowledge Diapedesis).

A separate group should include the so-called congestive, or venous, infarction, which is close to hemorrhagic, caused by the closure of the lumen and the cessation of the outflow of blood through relatively large venous trunks or thrombosis of a large number of small veins. Stagnation of blood, edema and massive hemorrhages create conditions that are incompatible

with the vital activity of tissues, a heart attack occurs. Such venous congestive infarctions are observed in the intestines with thrombosis of the mesenteric veins, in the kidneys with increasing thrombosis of the renal veins, in the spleen with blockage of the lumen of the splenic vein.

Simultaneously or sequentially, multiple infarctions of different localization, shape and size may occur in various organs. You can also observe the formation of fresh foci of necrosis along the periphery of older, organizing infarctions, as well as the appearance of fresh necrosis in the remaining areas of the parenchyma in the thickness of the infarction. This may be due to the progression of circulatory disorders with the capture of new vascular branches, for example, when a blood clot spreads into their lumen, deterioration of blood circulation due to a drop in blood pressure, or, as happens with myocardial infarction (see full body of knowledge), with sudden inadequate physical or emotional load. This is preceded by changes at the level of intracellular organelles and macromolecules - swelling and destruction of mitochondrial cristae, changes in the ultrastructure of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, accumulation of lipoprotein complexes

Rice. 1. Section of the spleen: arrows indicate white (ischemic) infarctions.

Rice. 2. Longitudinal section of the lung with areas of red (hemorrhagic) infarction (indicated by arrows); microslide at the bottom right (arrows indicate the affected area soaked in blood).

Rice. 3. Longitudinal section of the kidney: arrows indicate white infarcts; microscopic specimen on the lower right (the lower arrow indicates the area of the white infarction, the upper arrow indicates the hemorrhagic zone along the periphery).

Histochemically, in the infarction zone, a decrease and disappearance of glycogen is determined (in the myocardium, liver, kidneys), a decrease in the activity of redox enzymes, a decrease in the content of DNA and RNA, the accumulation of neutral mucopolysaccharides such as sialic acids, and a violation of ionic equilibrium. After a short-term reflex narrowing, the vessels in the infarction zone paralytically expand; Essentially, in this area (in the heart, lungs) there is not anemia, but venous congestion with a picture of stasis and small hemorrhages. Necrosis is of a coagulative nature (kidneys, spleen, myocardium) or from the very beginning takes on a wet, colliquating nature (in the brain). During a microscopic examination of a heart attack, the structure of the organ is disrupted, the nuclei are not stained and all structural elements merge into a homogeneous homogeneous mass (see full body of knowledge Necrosis). Along the periphery of a heart attack there is always a zone of necrobiosis, dystrophic changes and reactive inflammation. Based on the cellular composition of the inflammatory infiltration and the proliferative reactions of the stroma at the border of the infarction, one can judge the duration of the process. Small infarcts (microinfarcts) are replaced by young connective tissue within 3-4 days. In large infarcts, necrotic masses in the center of the lesion can persist for weeks or even months

The outcome of a heart attack depends on the conditions of its formation, location and size. Under favorable conditions, the heart attack is replaced by granulation and then scar tissue. A cyst develops in the brain at the site of wet necrosis. Lime may be deposited in the necrotic masses—petrification. Infarction. In the presence of microbes, the heart attack may undergo purulent melting. The pigment hemosiderin is found in scars at the site of a hemorrhagic infarction.

The significance of a heart attack for the body ultimately depends on its location, size, functional significance of the affected areas, regenerative and adaptive capabilities of the organ and tissues. Myocardial infarction and brain matter can cause death or cause severe dysfunction of the affected organ. Extensive heart attacks cause intoxication of the body with tissue decay products: an increase in temperature, a feverish state, and dystrophic changes in internal organs are noted. The absorption of denatured proteins from the lesion causes an autoimmune reaction with the formation of organ-specific antibodies and plasmatization of lymphoid formations.

The term “infarction” also refers to necrosis that develops in the kidneys when they are impregnated with uric acid salts (see the complete body of knowledge Uric acid infarction) or bile acids and hemoglobinogenic pigments (see the complete body of knowledge Bilirubin infarction).

Surgery for hemorrhagic stroke

The second stage of the treatment process is neurosurgical intervention. Its goal is to remove the life-threatening hematoma to improve survival and achieve the best possible satisfactory functional outcome. The sooner the operation is performed, the better prognosis can be expected. However, early surgery, as a rule, involves performing surgical procedures no earlier than 7-12 hours after the stroke. In the ultra-early period, it can lead to repeated bleeding.

When it is wiser to begin removing blood clots is decided by highly competent neurosurgeons. It was noted that operations performed even 2-3 weeks (inclusive) after the GI procedure can also lead to a positive effect. So the question of when to operate on a patient is entirely the responsibility of the doctor. Let us consider the fundamental surgical methods widely used for hemorrhagic strokes.

- Open decompressive craniotomy is indicated for medium and large subcortical, as well as large putamental and cerebellar hemorrhages. It is also addressed in case of pronounced displacement and increasing swelling of the cerebral component, deterioration of the patient’s neurological status. Open surgery is performed under complete general anesthesia using microsurgical optics. Removal of the accumulated clot is carried out through classic trepanation access. Next, an economical encephalotomy is performed, then the pathological component is sucked out with a special device. Dense accumulations are removed with fenestrated tweezers. At the end, the surgical field is thoroughly washed with sodium chloride solution, and thorough hemostasis is performed through coagulation and antihemorrhagic agents.

- The puncture-aspiration procedure is recommended for small hemorrhages of the thalamic, putamental, cerebellar location. The method consists of creating a small hole in the skull, puncturing the hematoma, and then freeing the brain from its liquid mass through aspiration. This technology can be implemented using one of two minimally invasive techniques: based on the principle of stereotactic or neuroendoscopic aspiration. Sometimes it is advisable to combine them with local fibrinolysis. Fibrinolysis involves installing drainage after puncture and aspiration into the hematoma cavity. Fibrinolytics are administered through the drainage over several days to activate the dissolution (liquefaction) of the blood clot and the removal of lysed blood elements.

Unfortunately, the functions of the central nervous system cannot be completely restored after hemorrhagic strokes. But in any case, it would be in the patient’s interests to go to a clinic where international-level doctors work in the diagnosis and surgical treatment of intracerebral lesions. This is the only way to ensure adequate and safe surgical support. Consequently, minimizing complications leads to more productive results in restoring quality of life.

We emphasize that the ideal execution of the operation in the right time increases the survival rate by 2-4 times. Proper postoperative care reduces the likelihood of relapse. It must be warned that a repeated stroke with hemorrhage in 99.99% of patients leads to death.

As a recommendation, we consider it important to say that the Czech Republic shows good results in the level of development of the field of brain neurosurgery in Europe. Czech medical centers are famous for their impeccable reputation and excellent rates of successful recovery of even the most difficult patients. And that’s not all: the Czech Republic has the lowest prices for neurosurgical care and one of the best postoperative rehabilitation. The choice of a medical institution for undergoing surgery, of course, remains with the patient and his relatives.

Hemorrhagic testicular infarction as a complication of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2)

Derevianko T.I., Pridchin S.V.

Information about authors:

- Derevianko T.I. – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head. Department of Urology, Pediatric Urology-Andrology, Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education "Stavropol State Medical University" of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation; Stavropol, Russia; RSCI Author ID 310494

- Pridchin S.V. – Assistant of the Department of Urology, Pediatric Urology-Andrology, Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “Stavropol State Medical University” of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation; Stavropol, Russia;

INTRODUCTION

Testicular infarction can occur in patients of all ages. Adult patients with this disease make up 7-10%, and children – 20% of the population of patients with acute urological pathology [1]. This is one of the urological nosologies, part of a group of diseases called “acute scrotum”. There are 2 types of testicular infarction: ischemic and hemorrhagic. According to the degree of organ damage, it is divided into segmental and total. Ischemic infarction occurs as a result of acute disruption of the blood supply to the testicle from the testicular artery. Most often this is caused by torsion of the spermatic cord or mechanical compression of the testicular vessels. Hemorrhagic infarction, as a rule, occurs as a result of impaired microcirculation or embolization of arteries and arterioles of the testicle and is most often segmental in nature [2]. Predisposing conditions for this may be an atherosclerotic process, in which artery occlusion occurs due to the formation of a large cholesterol embolus, as well as microangiopathy and often as a consequence of diabetes mellitus. Hemorrhagic testicular infarction can also occur in acute purulent orchiepididymitis, when blood circulation in the testicular vein system is disrupted [3]. A particularly difficult process occurs if the patient suffers from immunosuppressive diseases, as well as vasculitis and periarteritis.

Conditions associated with increased blood clotting also create conditions for venous obstruction with subsequent tissue necrosis in any organ, including the testicles [4-6]. It is known that COVID-19 (SARSCOV-2) causes a pathological increase in blood clotting in the patient’s body and its most dangerous complication is thrombus formation in various blood vessels of the patient’s organs, which often causes acute ischemia of these organs and even death in patients with COVID-19 [7-15].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We observed 3 clinical cases of hemorrhagic testicular infarction in patients suffering from COVID-19 (SARS-COV-2) and who were in the specialized COVID department of the city hospital in Pyatigorsk (Russia, Stavropol Territory). All 3 patients were aged from 67 to 88 years and had concomitant pathology of the cardiovascular system in the form of arterial hypertension, as well as type 2 diabetes mellitus.

We present a description of one clinical case, since they all followed the same clinical scenario.

Clinical observation. Patient V., 66 years old, was hospitalized in a specialized COVID department with a diagnosis of: Coronavirus infection caused by COVID19 (confirmed), moderate form UO7.1, community-acquired bilateral lobar pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory failure. Concomitant diseases: atherosclerotic cardiosclerosis, arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus. The patient received therapy for the underlying disease (antibacterial, anticoagulant therapy (Enoxaparin 40 mg once a day), anti-inflammatory, detoxification therapy), but on the 9th day of his hospital stay he began to complain of acute pain in the left half of the scrotum, sharp (in within several hours) increase in the size of the left testicle. Over the next 24 hours, according to the patient, the pain and volume of the testicle increased. The patient constantly had febrile body temperature during his hospital stay. Considering the profile of the department and the specificity of the situation, the examination by a urologist took place only 42 hours after the complaints arose.

Examination: the left half of the scrotum is enlarged in size, its skin has a bluish tint. The left testicle is doubled in size, dense, painful, and not fused with the surrounding tissues. The patient notes a slight decrease in pain intensity relative to its debut. General and local hyperthermia persists.

History: He did not suffer from diseases of the kidneys, urinary tract or male gonads during his life.

Instrumental and laboratory studies: diaphanoscopy revealed the impermeability of the entire testicular tissue to the light beam. Ultrasound examination (ultrasound) of the left testicle revealed a wide wedge-shaped hypoechoic damage to the testicular parenchyma with signs of severe ischemia, occupying almost all of its tissue. This result indicated an acute circulatory disorder in the left testicle. During the hospital stay, an increase in symptoms was noted. A laboratory blood test revealed an increase in the number of leukocytes and indicators of the blood coagulation system, acceleration of ESR and an increase in the concentration of C-reactive protein. These studies were carried out over time and there was a tendency towards their increase during the hospital stay.

For the purpose of differential diagnosis between a heart attack and testicular cancer, tests were performed for the tumor markers AFP (Alphafetoprotein), B-hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) and LDH (lactate dehydrogenase). They were normal, indicating the absence of an oncological process in the left testicle. Duplex scanning revealed signs of hemorrhage and necrosis and a decrease in the degree of pulsation of the left testicular artery, which indicated the presence of a left testicular infarction. All studies were objective indications for emergency surgical exploration of the left testicle.

Treatment. Emergency surgical exploration of the left testicle was performed. It was increased in size, purple-bluish in color, dense with multiple areas of hemorrhage and necrosis (Fig. 1). No spermatic cord torsion was noted. The condition of the testicle was assessed as a segmental extensive hemorrhagic infarction of the testicular parenchyma. A left orchiectomy was performed.

Rice. 1. Surgical specimen, isolated left testicle with necrotic changes and hemorrhages of all tissues 1. Surgical preparation, left testicle with necrotic changes and hemorrhages of all tissues

Histological examination of the surgical specimen (removed left testicle) revealed the presence of testicular tissue necrosis, altered red blood cells and extravasation in the tissues of the organ, which confirmed the diagnosis of hemorrhagic testicular infarction in this patient. The reason for this was most likely the underlying disease - COVID-19 (SARS-COV-2), which pathologically increased the coagulation properties of the patient's blood and caused an acute local vascular catastrophe in the left testicle.

DISCUSSION

Two other patients of our clinical observation were also in the same department for COVID-19 disease (SARS-COV-2) and had a similar clinical picture of hemorrhagic testicular infarction on days 10 and 12 of the underlying disease. After a preliminary examination and surgical revision of the testicle, they also underwent an emergency orchiectomy. All 3 patients recovered.

There are no other similar cases described in the available literature.

CONCLUSION

Hemorrhagic testicular infarction in patients with COVID-19 in our clinical observation can be considered as a complication of COVID-19 or as its clinical manifestation in the organs of the male reproductive system.

LITERATURE

- Nechiporenko N.A., Nechiporenko A.N. Emergency conditions in urology. Minsk. Higher School, 2012; 400 s. .

- Bolotov Yu.N., Minaev S.V. Acute testicular diseases in children. Practical guide. M.: INFRA-M, 2018; 107 p. [Bolotov Yu.N., Minaev SV Acute testicular disease in children. A practical guide. M.: INFRA-M, 2018; 107 p. (In Russian)]. https://doi.org/10.12737/2899.

- Madaan S, Joniau S, Klockaerts K Costa M, Calleja R, Ball RY, Burgess N. Segmental testicular infarction. Conservative management is feasible and safe: part 2. Eur Urol 2008;53(3):656-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.062.

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2021. N Engl J Med 2020;382(8):727-733. https://doi.org/10.1056/ NEJMoa2001017.

- Ge H, Wang X, Yuan X, Xiao G, Wang C, Deng T, et al. The epidemiology and clinical information about COVID-19. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39(6):1011-1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-020-03874-z.

- Sifuentes-Rodriguez E, Palacios-Reyes D. COVID-19: the outbreak caused by a new coronavirus. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex 2020;77(2):47-53. https://doi.org/10.24875/BMHIM.20000039.

- Baloch S, Baloch MA, Zheng T, Pei X. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Tohoku J Exp Med 2021 Apr;250(4):271-278. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.250.271.

- Steinberg E, Balakrishna A, Habboushe J, Shawl A, Lee J. Calculated Decisions: COVID-19 Calculators During Extreme Resource-Limited Situations. Emerg Med Pract 2020;22(4 Suppl):CD1- CD5.

- Malkhasyan V.A., Kasyan G.R., Khodyreva L.A., Kolontarev K.B., Govorov A.V., Vasiliev A.O., Pushkar D.Yu. Providing inpatient care to urological patients in the context of the coronavirus infection pandemic COVID-19. Experimental and Clinical Urology 2020;(1):4-11. . https://doi.org/10.29188/2222-8543-2020-12-1-4-1.

- Stensland KD, Morgan TM, Moinzadeh A, Lee CT, Briganti A, Catto J, Canes D. Considerations in the triage of urologic surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol 2020;77(6):663‐666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.027.

- Un contagio su dieci tra medici e infermieri, in trincea con mascherine inadatte e pochi tampon. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/ un-contagio-dieci-%0Amedicie infermieritrinceamascherine-inadattee-pochi-tamponi-ADqwiFF.

- EAU Robotic Urology Section (ERUS) guidelines during COVID-19 emergency. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://uroweb.org/eau-robotic-urology-section-erus-guide-lines-during-c…, accessed on March 29, 2021.

- Ficarra V, Novara G, Abrate A, Bartoletti R, Crestani A, de Nunzio C, et al. Urology practice during COVID-19 pandemic. Minerva Urol Nephrol 2020; 72(3):369-375. https://doi.org/10.23736/ S03932249.20.03846-1.

- Hollander J, Car B. Virtually Perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020(382)1679- 168. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2003539.

- Moazzami B, Razavi-Khorasani N, Dooghaie Moghadam A, Farokhi E, Rezaei N. COVID-19 and telemedicine: immediate action required for maintaining healthcare providers well-being. J Clin Virol 2020(126):104345. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd4029942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.10434513.

Magazine

Journal "Experimental and Clinical Urology" Issue No. 2 for 2021

Comments

To post comments you must log in or register