Causes of infective endocarditis

Infectious endocarditis can be caused by various bacteria and microscopic fungi, the biological properties of which allow them to grow and multiply by attaching to the tissues of the heart.

Infective endocarditis is one of the most dangerous cardiac diseases. Mortality even with intensive treatment in a specialized hospital is very high (according to various sources, from 15 to 25%). And if endocarditis is not treated, it is guaranteed to “eat” the heart valves, blood circulation will become impossible and the patient will die.

Routes of infection

The first way is infection of the natural “channels” leading into the body - skin, teeth, urinary tract, female reproductive system. The entry of a microorganism into any blood vessel gives it a chance to travel through the bloodstream to the heart.

The second way is artificial. Any violation of the integrity of the skin and mucous membranes (usually with the help of medical instruments or needles) can lead to infection entering a blood vessel. Hence the increased incidence of infective endocarditis in drug addicts and patients who have undergone various types of surgical interventions - from tooth extraction to operations to replace heart valves. It is clear that the greater the volume of intervention, the higher the potential threat of infection. In this regard, during surgical interventions one or another antibiotic prophylaxis regimen is used.

Etiology and routes of infection

The causative agents of endocarditis are most often microorganisms such as streptococci, staphylococci, enterococci, but the cause of the disease can also be representatives of the normal microflora of the oropharynx, upper respiratory tract, as well as fungi. Infection can enter the body, for example, during surgical interventions (prosthetic valves, catheterization of large vessels, and even tooth extraction). The likelihood of IE is quite high in patients with weakened immunity and the presence of foci of chronic infection (chronic tonsillitis, boils). Endocarditis often develops against the background of pre-existing cardiac pathology.

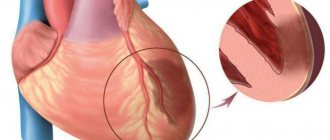

From the entrance gate of the infection, the pathogen enters the heart cavity with the bloodstream, settles on the valve flaps and forms vegetations (growths). The surface of the valves becomes ulcerated and deformed. Most often, the aortic and mitral valves are damaged, less often the tricuspid and pulmonary valves. Platelets and fibrin threads, responsible for the formation of blood clots, settle here. Once the valve leaflets become so deformed that they cannot close completely, a valve defect is formed, which in turn can lead to heart failure.

Microbial vegetations also pose a great danger because their elements can break off from the endocardium and spread through the bloodstream throughout the body, infecting other organs and tissues and leading to blockage (embolism) of large vessels. That is why, with endocarditis, the blood supply to the kidneys, spleen, lungs, brain, and also the heart itself is disrupted.

Clinical picture of the disease

The clinic of infective endocarditis is formed by three components.

The first is septic (when any infection enters the bloodstream, a high temperature, severe weakness, increased heart rate, and disorders of the blood coagulation system develop).

The second component is the manifestation of local infection. Microorganisms form colonies on the inner lining of the heart, most often on the valves - the so-called vegetations. Vegetations can be detected by ultrasound examination of the heart. Sometimes they are not visible with conventional echocardiography, and then an ultrasound examination through the esophagus (similar to gastroscopy, only with a special ultrasound probe) is necessary for diagnosis.

The third component is the consequences of the separation of vegetations from the valves - blockage of blood vessels by vegetations (embolism). Pieces of vegetation can “fly away” into any blood vessels - the brain, heart, kidneys, limbs, lungs, causing the death of the corresponding tissues due to impaired blood flow, which is accompanied by clinical manifestations of damage to a specific organ.

If a patient with a high temperature (fever) of unknown origin lasting more than a week, which does not respond to conventional treatment with antibiotics, has additional symptoms (heart murmurs or disturbances in organs into the vessels of which a torn piece of vegetation has “flown”), examination for the presence of infective endocarditis is necessary .

Diagnosis of infective endocarditis

An accurate diagnosis of endocarditis is made by positive blood culture results and reliable visualization of intracardiac vegetations. In all other cases, the diagnosis of endocarditis is made with varying degrees of probability.

The following types of research are used:

- Laboratory diagnostics;

- Electrocardiography (ECG);

- Echocardiography;

- X-ray of the chest organs.

1 Consultation with a MedicCity cardiologist

2 ECG as a method for diagnosing infective endocarditis

3 Full description of the picture

Treatment of infective endocarditis

Treatment for infective endocarditis begins with high doses of serious antibiotics, usually intravenous. Treatment continues, depending on the specific type of pathogenic microorganism, from two to six weeks. If treatment is ineffective (high temperature, further growth of vegetations according to echocardiography), a decision is made on surgical treatment (the heart is opened, vegetations are cleaned out, and, if necessary, the affected valve is replaced with an artificial one). However, as previously described, treatment is not always successful, and despite medical advances, the mortality rate of infective endocarditis has not been significantly reduced.

Measures to prevent infective endocarditis

If you need any surgical intervention (from tooth extraction to abdominal surgery), be sure to ask your doctor if any action on your part is needed for antibiotic prophylaxis for infective endocarditis (sometimes preventive antibiotic therapy is already included in the hospital treatment plan). If the doctor gives recommendations for taking antibiotics at home, be sure to follow them.

If you accidentally slightly damage the skin (cut), be sure to treat the wound with an antiseptic (alcohol, brilliant green or iodine). If the cut or puncture is deep, you should immediately take an antibiotic (for example, if you are not allergic to penicillin, Augmentin 1 gram once).

At MedicCity you can undergo a comprehensive cardiological examination and treatment of identified cardiovascular diseases. Reception is carried out by highly qualified cardiologists using expert equipment.

Antibacterial therapy and prevention of infective endocarditis in modern conditions

The problem of infective endocarditis (IE) still remains important due to high mortality rates and the development of severe complications. Timely informing doctors about modern methods of treating IE is of great practical importance. The article presents the basic principles of antibiotic therapy and prevention of IE, taking into account the latest recommendations of experts from the European Society of Cardiology.

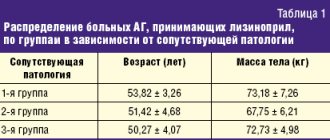

Table 1. Antibiotic therapy for IE caused by oral streptococci and Streptococcus bovis

Table 2. Antibiotic therapy for IE caused by staphylococci

Table 3. Antibiotic therapy for IE caused by enterococci

Table 4. Antibiotic therapy for IE caused by rare pathogens

Table 5. Empirical regimens of antibacterial therapy for acute IE (before identification of the pathogen)

Table 6. Recommendations for the prevention of IE during high-risk dental procedures in high-risk patients

Infective endocarditis (IE) continues to be characterized by severe morbidity and high mortality. Due to the extreme urgency of the problem, many national and international medical associations have published both initial and updated recommendations regarding the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of IE, as well as its complications. The provisions of these recommendations are of undoubted interest both for researchers and for practicing physicians supervising patients with IE.

The article discusses the treatment and prevention of IE, taking into account the latest recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)1.

Treatment

General principles

Antibacterial therapy for IE should be early, massive and long-term (at least four to six weeks). This takes into account the sensitivity of the isolated pathogen to antibiotics. In patients with IE, bactericidal antibiotics should be used, the advantages of which over bacteriostatic ones have been demonstrated in both experimental and clinical studies.

The presence of pathogens in vegetation and biofilm (the latter is especially important in case of IE of valve prostheses (IEP)) requires high-dose and long-term antibiotic therapy.

One of the main obstacles to drug eradication of infection may be bacterial tolerance to the antibiotic, that is, the pathogen becomes insensitive to the bactericidal effect of the drug while maintaining susceptibility to the bacteriostatic one. Escape of the killing effect of the antibiotic may be the reason for the resumption of growth of the pathogen population after cessation of therapy, which leads to relapse of the disease. Therefore, in some cases, a combination of bactericidal drugs may be more preferable than monotherapy.

Antibacterial therapy

Infectious endocarditis caused by penicillin-sensitive oral streptococci and Streptococcus bovis.

Recommended treatment regimens for endocarditis caused by penicillin-sensitive streptococci (minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibiotics ≤ 0.125 mg/l) are presented in Table. 1. If renal function is normal, the daily dose of gentamicin or netilmicin is administered once. If you are allergic to beta-lactams and cannot undergo desensitization, vancomycin is prescribed.

Endocarditis caused by penicillin-resistant oral streptococci and Streptococcus bovis.

Penicillin-resistant oral streptococci are classified as moderately resistant (MIC 0.25–2.00 mg/L) and completely resistant (MIC ≥ 4 mg/L). Antibacterial therapy for this form of IE is similar to the treatment for IE caused by penicillin-sensitive oral streptococci (see Table 1). In case of penicillin resistance, aminoglycosides should be prescribed for at least two weeks. Short-term courses of treatment with beta-lactams are not recommended. In the presence of highly resistant strains (MIC ≥ 4 mg/ml), preference is given to vancomycin in combination with aminoglycosides. The requirement to monitor serum concentrations of gentamicin is not always feasible in domestic general hospitals. Therefore, based on practical considerations, an intermittent regimen of gentamicin is justified. The drug is prescribed for seven to ten days with a break of five to seven days to prevent toxic effects. Then a repeat course is carried out with the same doses.

Infectious endocarditis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, beta-hemolytic streptococci of groups A, B, C, G.

In the presence of penicillin-sensitive strains

of St.

pneumoniae (MIC ≤ 0.06 mg/l) therapy is similar to the treatment of IE caused by oral streptococci (see Table 1), with the exception of a two-week course, the effectiveness of which has not been studied. Similar regimens are used in the presence of strains with moderate (MIC - 0.125–2,000 mg/l) and complete resistance (MIC ≥ 4 mg/l), excluding meningitis. However, some authors in such cases recommend therapy with cephalosporins in higher doses or vancomycin.

IE caused by hemolytic streptococci A, B, C, G is relatively rare. The regimens for its antibacterial therapy are similar to those given above. Short-term courses of treatment are not recommended. It is advisable to use Gentamicin for two weeks or intermittently.

Infectious endocarditis caused by Granulicatella and Abiotrophia, that is, species of streptococci with altered nutritional requirements (nutritionally).

This form of IE is characterized by a long development of clinical symptoms, the formation of large vegetations (> 10 mm), a high incidence of complications and the need for replacement of the affected valve (50% of cases), which is probably due to late diagnosis and treatment. Recommended antibiotic regimens are six-week courses of penicillin G, ceftriaxone, or vancomycin in combination with an aminoglycoside for at least the first two weeks.

Endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS).

IE associated with

S. aureus

is characterized by an acute course and a pronounced destructive process in the valves, while with CoNS the development of the clinical picture is more prolonged in time.

Table 2 provides recommendations for the treatment of native valve IE (NVI) and VEI caused by both methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) strains of S. aureus

and CoNS.

The use of aminoglycosides for staphylococcal IEN is not recommended. Short-term (two weeks) and oral therapy is appropriate for uncomplicated right-heart MSSA-IE. However, these schemes are not applicable for left-hearted forms. If it is not possible to prescribe beta-lactams, daptomycin is indicated in combination with another antistaphylococcal drug. This will increase the activity of treatment and prevent the development of resistance. As an alternative for treating S. aureus

IE, some experts recommend adding high-dose clindamycin to co-trimoxazole.

For PEC caused by S. aureus

, there is a high mortality rate (up to 45%), which may require early valve replacement. Distinctive features of the treatment of this form of IE are an increase in the duration of the course of antibiotics, the addition of aminoglycosides and the administration of rifampicin three to five days from the start of therapy, that is, after the bacteremia has been eliminated. The addition of rifampicin to the treatment regimen for staphylococcal IE is standard practice, but the level of evidence for this use is poor. Treatment may be accompanied by an increase in microbial resistance, the development of hepatotoxicity and unwanted drug interactions.

Infectious endocarditis caused by methicillin-resistant and vancomycin-resistant staphylococci.

MRSA is generally resistant to many antibiotics except vancomycin.

However, in recent years, S. aureus

highly resistant to vancomycin have been isolated from patients with severe infections, which required the search for new approaches to therapy.

In this regard, the lipopeptide antibiotic daptomycin is of particular interest, the use of which in S. aureus

bacteremia and right heart IE was previously approved.

According to the results of cohort studies that included patients with S. aureus

-IE and CoNS-IE, the effectiveness of daptomycin is comparable to vancomycin. To prevent the increase in resistance in patients with IEN, daptomycin is prescribed in high doses (≥ 10 mg/kg) in combination with beta-lactams or fosfomycin. According to most experts, this combination increases the binding of daptomycin to the bacterial cell wall by reducing the positive surface potential. For PECI, gentamicin and rifampicin should be added to daptomycin. Other treatment options include fosfomycin + imipenem, new beta-lactams (ceftaroline) with better affinity for penicillin binding protein 2a, quinupristin/dalfopristin ± beta-lactams, vancomycin + beta-lactams, and co-trimoxazole (in high doses) + clindamycin."

Endocarditis caused by enterococci.

In the presence of enterococcal strains sensitive to penicillin (MIC ≤ 8 mg/ml), treatment is carried out with penicillin G or ampicillin (preferred) in combination with gentamicin (Table 3).

The use of ampicillin simultaneously with ceftriaxone for Enterococcus faecalis

-IE is similar in effectiveness to the combination of ampicillin and gentamicin.

In case of high resistance to gentamicin (MIC > 500 mg/l), streptomycin is used at a dose of 15 mg/kg/day in two doses. In case of resistance to beta-lactams, two options are possible:

- for the production of beta-lactamases, replace ampicillin with ampicillin/sulbactam;

- modifications of penicillin-binding protein 5 – regimens with vancomycin.

In case of multiresistance to aminoglycosides, beta-lactams and vancomycin, the following alternative regimens are proposed:

- daptomycin 10 mg/kg/day plus ampicillin 20 mg/kg/day IV in four to six injections;

- linezolid 1200 mg/day IV or orally in two doses for eight weeks or more (monitoring of bone marrow function is necessary);

- quinupristin/dalfopristin three times 7.5 mg/kg/day for eight weeks or more (not active against E. faecalis

).

Before prescribing other combinations (daptomycin plus ertapenem or ceftaroline), you should consult with an infectious disease specialist.

Infectious endocarditis caused by gram-negative bacteria.

This type of endocarditis is divided into two groups.

HACEK-IE is associated with Gram-negative rods ( Haemophilus

spp.

, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans

,

Cardiobacterium hominis

,

Eikenella corrodens

,

Kingella kingae

and

Kingella denitrificans

), which require special culture conditions. The standard treatment regimen is ceftriaxone 2 g/day for four weeks for IENP or six weeks for IEPC. In the absence of beta-lactamase synthesis, a combination of ampicillin (12 g/day IV in four to six injections) with gentamicin (3 mg/kg/day IV in two to three injections) is used for four weeks. Ciprofloxacin can be used (800–1200 mg/day IV in two to three doses or 1500 mg/day orally in two doses), but this regimen has been less studied. For IE caused by bacteria not belonging to the HACEK group, management tactics include early surgical treatment and long-term (more than six weeks) therapy with a combination of beta-lactams and aminoglycosides, in some cases with the addition of fluoroquinolones or co-trimoxazole.

Infective endocarditis with negative blood culture

. The disease develops in 31% of cases. The leading reason is the prescription of antimicrobial drugs to patients with a presumptive diagnosis of IE before taking blood for a blood culture study. Identification of rare microorganisms requires special equipment and specific serological techniques.

The basic principles of treatment (after verification of the pathogen) are presented in table. 4.

The optimal duration of treatment for IE caused by these pathogens is unknown. Treatment periods are indicated only in individual reports.

It must be emphasized that therapy for Whipple's disease remains empirical. In case of damage to the central nervous system, doxycycline is combined with sulfadiazine 6 g/day orally in four doses. Alternative therapy is ceftriaxone 2 g/day or penicillin G 12 million units in six doses in combination with streptomycin 1 g/day IV for two to four weeks, followed by co-trimoxazole 1600 mg/day in two doses. Trimethoprim is not active against Tropheryma whipplei

. However, data have been obtained on successful long-term (more than a year) treatment with co-trimoxazole.

For IE caused by Candida

spp., recommend liposomal amphotericin B in combination with flucytosine or echinocandin (caspofungin) in high doses.

In patients with Aspergillus

-IE, voriconazole is the drug of choice and can be combined with an echinocandin or amphotericin B.

With such IE, as a rule, the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy is low, so cardiac surgery is required. In the postoperative period, long-term (sometimes lifelong) therapy with fluconazole ( Candida

-IE) or voriconazole (

Aspergillus

-IE).

Empirical antibiotic therapy

In case of acute IE, antibacterial therapy is prescribed empirically immediately after taking blood from a vein three times (with an interval of half an hour to an hour) for blood culture testing.

When choosing a treatment regimen, take into account:

- presence of previous antibiotic therapy;

- IENK or IEPK with clarification of the timing of the operation (early or late IEPK);

- place of infection (community-acquired, nosocomial or non-nosocomial, associated with the provision of medical care for IE), data on local antibiotic resistance and the prevalence of IE pathogens that require special cultivation conditions;

- In the empirical treatment of MSSA bacteremia/endocarditis, oxacillin/cefazolin is associated with lower mortality rates compared with other beta-lactams and vancomycin.

Schemes of empirical antibiotic therapy for acute IE are presented in Table. 5.

In patients with IEC and late IEC, therapy should be directed against pathogens such as staphylococci, streptococci and enterococci. Treatment of early IEPC and health care-associated IE should target MRSA, enterococci, and gram-negative pathogens (except HACEK).

It is important to note that for healthcare-associated IE in areas where the prevalence of MRSA infections is greater than 5%, some experts recommend combining vancomycin with oxacillin until information about the causative agent is available. Rifampicin is recommended only for IEPC. According to some experts, it should be prescribed three to five days after the start of therapy with vancomycin and gentamicin.

After identifying the pathogen and determining its sensitivity to antibiotics, appropriate adjustments are made to the treatment regimen, if necessary.

If the pathogen cannot be isolated even using available modern diagnostic methods, it is advisable to continue empirical therapy for at least five to seven days. The appearance of the first signs of a clinical effect (decrease in temperature, disappearance of chills, decrease in weakness, improvement in general well-being) serves as the basis for continuing treatment (full course - four to six weeks). In the absence of positive dynamics, it is necessary to change the antimicrobial therapy regimen.

Surgery

If drug therapy is ineffective, surgical treatment is indicated. The main indications for it are:

- uncorrectable progressive congestive circulatory failure;

- an infectious process not controlled by antibiotics; fungal endocarditis;

- myocardial abscesses, sinus or aortic aneurysms;

- the presence of large vegetation;

- repeated episodes of thromboembolism.

Active IE is not a contraindication to surgical treatment.

Prevention

According to the recommendations of ESC experts, prevention of IE is indicated only for patients with a high risk of an unfavorable outcome (this position is disputed by a number of specialists) who undergo dental procedures with the highest risk of developing bacteremia (manipulation of the gums or periapical area of the teeth, perforation of the oral mucosa).

High-risk groups include:

- patients with any valve prosthesis, including transcatheter valve implantation, or patients in whom any prosthetic material was used for heart valve repair;

- patients with a history of IE;

- patients with congenital heart disease (CHD): any type of cyanotic (blue) CHD;

- any type of congenital heart disease that is reconstructed with prosthetic material, performed surgically or using percutaneous technology - up to six months after surgery or for life if there is a residual shunt or valvular regurgitation.

Recommendations for preventive measures are presented in table. 6. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended:

- with other valvular or congenital heart disease;

- when performing manipulations on other organs and tissues in the absence of local infection.