Lisinopril: active ingredients

The name of the drug is identical to its active substance - lisinopril dihydrate. Separately, you can find the drug under other trade names. As a rule, its cost under other names is significantly higher.

The following can be used as auxiliary components by various manufacturers:

- corn starch or pregelatinized;

- calcium hydrogen phosphate;

- mannitol;

- magnesium stearate;

- colloidal silicon dioxide;

- microcrystalline cellulose;

- talc.

The drug is produced in the form of oblong white tablets. Its edges are rounded and there is a risk in the center. Each tablet contains 5 mg, 10 mg or 20 mg of active ingredient. The medicine is packaged in 10 tablets in a blister. The package contains 30 doses (3 blisters).

Lisinopril analogs

The original Lisinopril has an affordable price, but there are still many generics (analogs of the drug from different manufacturing countries) on the market.

Substitutes (synonyms) for Lisinopril in Russia

- Lisinopril-Ratiopharm;

- Diroton (Hungary);

- Diropress (Germany, Slovenia);

- Iruzid (Croatia);

- Ko-Diroton (Poland, Hungary);

- Lysigamma (Germany);

- Rileys-Sanovel (Türkiye);

- Scopril (Macedonia);

- Equator (Hungary, Russia).

Lisinopril is available in the form of tablets of 5, 10 and 20 mg.

There are also many medications on the market that combine Lisinopril with other groups of antihypertensive substances:

- with Amlodipine (Equator, Tenliza);

- with Hydrochlorothiazide (Co-Diroton, Lisinopril-H,HL, Lizoretik);

- with Indopamide (Diroton-Plus).

Such combinations were created to simplify the regimen and reduce the number of tablets, which increases the likelihood of systematic use of the drug.

How does Lisinopril work?

The drug acts on the renin-angiotensin system of the heart, interfering with dilatation of the left ventricle. At the same time, there is a decrease in the load on the myocardium. The substance reduces pressure in the capillaries of the lungs, as well as in peripheral vessels. When treated with Lisinopril, the tolerance of the cardiac myocardium to increased stress increases. In addition, the activity of renil in plasma increases.

After taking a single dose, the first positive effect occurs after 50-60 minutes. The manifestation of the therapeutic effect intensifies within 7 hours and persists throughout the day. Therapy lasting for several weeks achieves the maximum possible hypotensive effect.

Eating does not interfere with the absorption of the active substance, but at the same time does not contribute to it. Therefore, taking the medicine does not depend on the time of eating. Absorption of Lisinopril reaches 25%. The drug molecules bind weakly to blood proteins. Half-life occurs after 12 hours. Substances are excreted unchanged by the kidneys. Lisinopril does not form metabolites.

Efficacy and safety of lisinopril

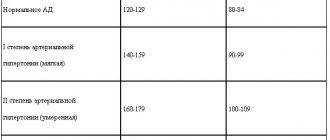

The chemical structure of lisinopril contains a carboxyl group, which binds the zinc-containing domain of ACE. Unlike most ACE inhibitors, lisinopril is not a prodrug. Absorbed into the gastrointestinal tract, it does not undergo further metabolic transformations and is excreted unchanged by the kidneys. The drug has fairly variable bioavailability - from 6 to 60%. Lisinopril is not lipophilic and practically does not bind to plasma proteins. Its action begins an hour after oral administration, the peak effect develops after 4–6 hours, and the duration of action reaches 24 hours, which provides a convenient administration regimen - once a day. Today, drugs that suppress the activity of the renin-angiotensin system play a leading role in the fight against the main cause of death - cardiovascular diseases. Arterial hypertension (HTN) is called the “silent killer” because it is often asymptomatic, but plays an important role in the development of various diseases leading to death. Lisinopril has been used for the treatment of arterial hypertension for a long time, and currently a lot of data has been accumulated confirming the good effectiveness of lisinopril compared to other ACE inhibitors and antihypertensive drugs of other groups. A direct comparison of the effectiveness of two ACE inhibitors, enalapril and lisinopril, was carried out using blood pressure monitoring to monitor the effectiveness of therapy. The target BP was set to 140/90 mm Hg, and the dose of both drugs was titrated to achieve this BP level. Hydrochlorothiazide was added if necessary. Both drugs significantly reduced blood pressure, but the effect of lisinopril was more pronounced. The average doses of drugs at the end of the study were 18 mg enalapril and 8 mg hydrochlorothiazide in one group, and 17 mg lisinopril and 6 mg hydrochlorothiazide in the second group. It turned out that with the same administration regimen (once daily), lisinopril has a longer duration of action. The safety of the drugs was comparable [14]. A study conducted in 367 patients with mild and moderate hypertension directly comparing the effectiveness of enalapril and lisinopril showed that lisinopril at a dose of 10–40 mg per day was more effective than enalapril at a dose of 5–20 mg per day [17]. A direct comparison of the effectiveness of lisinopril and quinapril was carried out. The study included 50 patients with mild and moderate hypertension. The therapy lasted two months. The effectiveness of antihypertensive therapy was monitored using blood pressure monitoring. The study showed that lisinopril was better at lowering both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Both drugs did not cause significant changes in the blood lipid spectrum and glycemic levels [21]. A relatively small study (65 patients with DBP 95–115 mm Hg) compared the effectiveness and tolerability of lisinopril and the b-blocker nebivolol. Lisinopril was prescribed at a dose of 20 mg once daily, nebivolol - 5 mg once daily. Both drugs caused a significant decrease in blood pressure and were well tolerated by patients [24]. The purpose of a cooperative study conducted in Denmark was to comparatively evaluate the effectiveness and tolerability of lisinopril and felodipine in patients with grade 1 and 2 hypertension. A total of 219 patients were included in the study and randomized to receive felodipine 5–10 mg or lisinopril 10–20 mg per day. In general, lisinopril at this dosage was more effective than felodipine. In the subgroup of elderly patients, both drugs were equally effective. Lisinopril was slightly better tolerated by patients. The main side effects were dizziness, weakness and dry cough. For felodipine, the most common side effects were peripheral edema [16]. Lisinopril was more effective than felodipine in the treatment of grade 1 and 2 hypertension. A Norwegian multicenter study examined the antihypertensive efficacy, tolerability, and impact of these two drugs on quality of life in 828 patients with mild to moderate hypertension. The average dose of lisinopril at the end of the study was 18.8, nifedipine - 37.4 mg per day. Lisinopril was more effective in reducing systolic and diastolic blood pressure, was better tolerated by patients, and had a lower incidence of side effects. Both drugs had an equally good effect on the quality of life of patients [22]. The effectiveness of lisinopril and the imidazoline receptor agonist rilmenidine was compared in women with metabolic syndrome. Lisinopril was prescribed at a dose of 10 mg, rilmenidine at a dose of 1 mg per day. At the same time, both drugs reduced blood pressure equally. When treated with these drugs, there was a tendency to normalize blood lipid levels and reduce blood glucose levels [11]. The TROPHY study compared the antihypertensive efficacy of lisinopril and the diuretic hydrochlorothiazide using 24-hour blood pressure monitoring. The study included 124 patients with hypertension and obesity. Lisinopril was prescribed in doses of 10–40 mg, hydrochlorothiazide – 12.5–50 mg per day. The duration of treatment was 12 weeks. Both drugs significantly reduced blood pressure, the degree of reduction in systolic blood pressure was the same, and diastolic blood pressure decreased to a greater extent in the lisinopril group. In men, lisinopril was generally more effective than hydrochlorothiazide; in women, the drugs were equally effective. In black patients, the diuretic was more effective; in white patients, the ACE inhibitor was more effective. When dividing patients into groups according to the type of circadian rhythm of blood pressure, it turned out that non-dippers responded equally to therapy with both drugs, and in dippers, lisinopril was more effective [26]. A study was conducted to compare the effectiveness of lisinopril and the angiotensin II receptor blocker telmisartan (ARB): 32 previously untreated patients with hypertension were randomized to cross-over treatment with telmisartan 80 mg or lisinopril 20 mg per day. The effectiveness of the ACE inhibitor and BAR turned out to be the same both according to routine office blood pressure measurements and according to 24-hour blood pressure monitoring [25]. Another study (122 patients with stage 1 hypertension) showed equal antihypertensive efficacy of lisinopril, BAR - losartan and amlodipine. As expected, amlodipine caused peripheral edema more often than other drugs, and lisinopril caused dry cough [27]. In patients with severe hypertension, the effectiveness of fixed combinations of candesartan and lisinopril with hydrochlorothiazide was compared. The study included patients with a DBP level of 95–115 mmHg. persisted despite previous antihypertensive therapy. The duration of treatment was 26 weeks. The combination of 8 mg of candesartan and 12.5 mg of hydrochlorothiazide per day was received by 237 patients, 10 mg of lisinopril and 12.5 mg of hydrochlorothiazide - by 116 patients. Both combinations were found to be equally effective on diastolic blood pressure. As expected, a slightly higher incidence of side effects (dry cough) was found with the use of lisinopril [20]. The CALM II study (Long-Term Dual Blockade With Candesartan and Lisinopril in Hypertensive Patients With Diabetes) examined the effect of combination therapy with candesartan and lisinopril with high-dose lisinopril monotherapy on systolic blood pressure in patients with hypertension and diabetes. The study design was double-blind with two active treatment groups. Patients were randomized to receive lisinopril 40 mg or a combination of lisinopril 20 mg and candesartan 16 mg per day. The follow-up period was 12 months. The effectiveness of therapy was assessed using 24-hour blood pressure monitoring. The study included 75 patients with hypertension and diabetes with systolic blood pressure 120–160 mmHg. during treatment with lisinopril at a dose of 20 mg for at least a month. There were no significant differences between combination therapy and lisinopril therapy in the effect on blood pressure levels. The combination of lisinopril and candesartan was significantly better at reducing daytime blood pressure. Blood pressure at night and average blood pressure values over the day did not differ [10]. Lisinopril demonstrated comparable efficacy to the angiotensin II receptor blocker valsartan. The large randomized trial PREVAIL (Ehe Blood Pressure Reduction and Tolerability of Valsartan in Comparison with Lisinopril study) included 1213 patients with grade 1–3 hypertension (SBP 160–220 mmHg and DBP 95–110 mmHg. ). Patients were randomized to receive valsartan 160 mg or lisinopril 20 mg per day. After four weeks, if there was insufficient effectiveness, hydrochlorothiazide was added to therapy. The total duration of treatment was 16 weeks. 1100 patients completed the full course of treatment; 51 patients in the valsartan group and 62 patients in the lisinopril group discontinued treatment due to side effects of therapy. The decrease in blood pressure was identical in both treatment groups – 31.2/15.9 mmHg. and 31.4/15.9 mmHg. respectively. As expected, the lisinopril group had a higher incidence of dry cough (7.2% vs. 1.0%) [20]. Complications associated with severe hypertension have been known for a long time, but only in the last 30 years have doctors begun to treat patients with moderately elevated blood pressure in order to prevent complications. The prevalence of hypertension is 15–25%, and in people over 65 years of age it exceeds 50% [19]. The presence of elevated blood pressure, especially systolic, is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, heart and kidney failure. In patients with hypertension, an increase in overall mortality was found to be 2–5 times, and mortality from cardiovascular diseases – by 2–3 times [1]. Therefore, the development of treatment tactics for hypertension is one of the most important problems of modern cardiology. A large number of antihypertensive drugs of various groups creates certain difficulties when choosing the optimal medication for the correction of blood pressure. The choice of an antihypertensive drug in elderly patients is especially difficult due to the presence of multiple concomitant pathologies and the pharmacodynamics of drugs. Therefore, the data from multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled studies, covering the results of examination and treatment of many hundreds and thousands of patients, deserve attention. Studying the effect of long-term drug correction of hypertension with various groups of antihypertensive drugs (chlorthalidone, amlodipine, lisinopril, doxazosin) on mortality from coronary artery disease and the incidence of myocardial infarction in elderly patients was the goal of the ALLHAT study (Antihypertensive and Lipid–Lowering treatment to prevent Heart Attack Trial) [13] , the results of which were published in 2002. In the ALLHAT study, 15,255 patients received chlorthalidone at a dose of 12.5–25 mg, 9,048 patients received amlodipine at a dose of 2.5–10 mg, and 9,054 patients received lisinopril at a dose of 10–40 mg per day. If the target blood pressure level could not be achieved, then at the next stage a second drug was added (atenolol - 25-100 mg, reserpine - 0.05-0.2 mg once a day or clonidine - 0.1-0.3 mg twice a day day). If there was no effect, hydralazine was added at the third stage - 25-100 mg twice a day. None of these three drugs was shown to be superior in their ability to prevent the so-called primary composite endpoint of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality. The analysis of overall mortality also did not reveal any benefits of any drug. Lisinopril was slightly inferior to chlorthalidone in its ability to prevent strokes, hospitalization for angina, and worsening heart failure. This may be due to the fact that lisinopril was generally slightly worse at lowering blood pressure compared to chlorthalidone (SBP by 4 mmHg and DBP by 2 mmHg). The differences were especially large in people of the Negroid race, who are characterized by low sensitivity to ACE inhibitors. Overall, lisinopril therapy was more successful in white patients in the ALLHAT study. Thus, lisinopril was significantly superior to amlodipine in preventing decompensation of heart failure in whites; in patients of the Negroid race, the effectiveness of lisinopril and amlodipine did not differ significantly. The ALLHAT study conducted a genetic substudy, GenHAT, to determine whether genetic markers influence the effectiveness of antihypertensive therapy. The first results of the GenHAT study have already been published. The main candidate gene for the effectiveness of lisinopril was considered to be the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) gene and its type I/D polymorphic marker [12]. There is growing evidence that ACE inhibitors are the drugs of choice when hypertension is combined with diabetes mellitus (DM). It has been shown that in such patients ACEIs improve endothelial function and also reduce the risk of cardiovascular complications. In the study by I.G. Bereznyakov studied the effect of lisinopril on the severity of microalbuminuria (MAU) in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The choice of the research object is not random. In 80% of cases, hypertension precedes the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus, and in terms of importance in the progression of renal pathology, hypertension exceeds metabolic factors. Data indicate the high antihypertensive activity of lisinopril and the ability of the drug to reduce MAU after just a month of treatment, and these results were achieved in patients with diabetes who are at risk of microangiopathy [1]. In patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), ACEI therapy not only helps to slow down the progression of target organ damage (and above all nephropathy), but also helps to increase tissue sensitivity to insulin. Evidence of effectiveness has been obtained for lisinopril in this group of patients. The multicenter study EUCLID (Randomized placebo–controlled trial of lisinopril in normotensive patients with insulin–dependent diabetes and normoalbuminuria or microalbuminuria) examined the effect of lisinopril on the progression of diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) without arterial hypertension. A total of 530 patients with diabetes were included in the study and randomized to treatment with lisinopril or placebo. Therapy continued for two years. At the end of the study, the level of microalbuminuria in the lisinopril group was 18.8% lower than in the placebo group. The maximum effect was in patients who already had nephropathy at the beginning of the study. Patients receiving lisinopril had a significantly lower level of glycosylated hemoglobin (6.9% compared to 7.3%). Progression of retinopathy was observed in 13.2% of patients in the lisinopril group and in 24.3% of patients in the placebo group. The most interesting results of the study include data on a reduced risk of developing new cases of diabetes mellitus in patients receiving lisinopril compared with patients receiving chlorthalidone [13]. The incidence of new cases of diabetes diagnosed after two years of treatment was almost twice as high in patients receiving chlorthalidone compared with patients receiving lisinopril. The same trend persisted four years after the start of treatment. Patients taking lisinopril had lower blood glucose levels. These differences became significant after two years of the study and remained statistically significant until the end of the study. The use of ACEIs in elderly patients and patients with diabetes mellitus in comparison with calcium channel blockers (CCBs) is accompanied by a more pronounced reduction in the number of myocardial infarctions and cases of CHF (FACET, ABCD, STOP-Hypertension-2). One of the important requirements for modern antihypertensive drugs is their protective effect against damage to the main target organs in hypertension. Target organs include primarily left ventricular myocardial hypertrophy and nephropathy. The ELVERA (Effects of amlodipine and lisinopril on Left Ventricular mass) study examined the effects of lisinopril and amlodipine on myocardial mass and left ventricular diastolic function in elderly patients with arterial hypertension who were not receiving antihypertensive therapy. The study included 166 patients with arterial hypertension (DBP 95–115 mm Hg and SBP 160–220 mm Hg) aged 60 to 75 years: 81 patients received amlodipine at a dose of 2–10 mg per day , 85 patients received lisinopril at a dose of 10–20 mg per day. The observation period was two years. Both drugs have the same effect on the severity of left ventricular myocardial hypertrophy - the myocardial mass index decreased by 25.7 g/m2 in the amlodipine group and by 27 g/m2 in the lisinopril group. The effect of these two drugs on IMT of the carotid and femoral arteries was also studied. No significant differences in the effect of these two drugs on IMT were detected. The possibility of ACE inhibitors influencing cardiac arrhythmias and reducing the risk of sudden death was demonstrated by a study conducted by O.S. Sychev et al. in patients with coronary artery disease and hypertension who took lisinopril for 3 weeks. There was not only a significant decrease in blood pressure, but also a significant decrease in heart rate, as well as the number of supraventricular and ventricular extrasystoles, and atrial fibrillation runs [7]. Similar results were obtained in the work of O.A. Tsvetkova, in which a course of treatment with lisinopril in patients with COPD in combination with coronary artery disease led to a significant reduction in the number of supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias, primarily ventricular extrasystoles of high grades, which are given important prognostic significance in terms of the occurrence of fatal ventricular arrhythmias. The presence of pronounced rhythm disturbances in patients with COPD in combination with coronary artery disease may be due to a complex of factors observed in these patients, such as hypoxemia, myocardial ischemia, pulmonary hypertension, hypertrophy, dilatation. The decrease in the frequency of registration and the number of supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias can be explained by an improvement in blood gas composition, a decrease in the level of pulmonary hypertension, a decrease in hypertrophy and dilatation of the ventricles of the heart, an improvement in systolic and diastolic function of the LV, and a decrease in myocardial ischemia, which were noted under the influence of treatment with lisinopril [8]. The reduction in the number and severity of arrhythmias could be facilitated by the effects of lisinopril, such as a decrease in myocardial oxygen demand, a decrease in abnormal activation of the neurohumoral system, as well as a positive effect of lisinopril on the autonomic regulation of heart tone. Different classes of antihypertensive drugs have different effects on the progression of nephropathy. In a study that included 32 patients with arterial hypertension and hypertensive nephropathy, it was shown that lisinopril therapy alone improves renal function by reducing the level of albumin excretion and reducing renal vascular resistance. Therapy with nifedipine in combination with hydrochlorothiazide, with similar blood pressure control, did not affect renal function in patients with hypertensive nephropathy [5]. Several large prospective studies involving thousands of patients (CONSENSUS P, ISIS-4, SMILE, etc.) have convincingly shown that ACE inhibitors reduce mortality if they are prescribed in the early stages of myocardial infarction (MI). The non-selective GISSI-3 study [15] assessed the effectiveness of lisinopril, nitrates and their combination in the acute period of myocardial infarction at an initial daily dose of 5 mg, followed by an increase to 10 mg. Therapy in/in nitroglycerin or lysinopril began no later than 24 hours from the moment the symptoms occurred to them. The observation period was 6 weeks. A significant decrease in mortality was revealed by 11% and, in addition to the fact that in the Lisinopril group the risk of developing severe left ventricular dysfunction is reduced, in the group of patients who received lysinopril, compared with the control group, remodeling of the left ventricle is improved [4,6,15,18]. The available data also suggests that in the earliest stages of myocardial infarction, patients with large -focal myocardial infarcts of the anterior localization, as well as patients with repeated heart attacks, need. The duration of the therapy of IACs should be at least 6 months, after which it is necessary to re -assess the function and size of the left ventricle [4,18]. One of the studies where the ACE inhibitors were conducted by the Smile -2 (Survival of MyCardial Infarction) study, which compared the effectiveness of zofenopril at a dose of 30–60 mg and lisinopril at a dose of 5-10 mg per day. Both drugs were prescribed to patients who received thrombolytic therapy for acute them. ACE inhibitors began no later than 12 hours after the completion of thrombolysis and lasted 42 days. A total of 1024 patients were included in the study. There were no reliable differences in the risk of cardiovascular complications in both groups of treatment [9]. The ATLAS randomized study compared the effectiveness and tolerance of prolonged therapy with low and high doses of lysinopril in 3164 patients with CHA II - IV FC and an emission faction of not more than 30%. After randomization, half of the patients received lysinopril in a daily dose of 32.5–35 mg, and the other half at a dose of 2.5–5 mg. During the observation in the group of patients who received high doses of lysinopril, there was lower mortality from all causes (by 8%) and mortality from cardiovascular causes (by 10%). The total number of cases of death and hospitalization was significantly less in a group of lysinopril treated with high groups compared with patients who received low doses of the drug (12%). Therapy with high doses of lysinopril led to a significant decrease in the need for hospitalization in connection with the decompensation of heart failure (by 24%) [23]. Therefore, according to the ATLAS study, the use of high doses of ACE inhibitor of lysinopril can significantly reduce the need for hospitalization, as well as reduce the risk of death of patients with heart failure. In addition to clinical efficiency and tolerance, the main characteristics of various treatment or prevention strategies include cost effectiveness. In order to recommend the use of the drug in conditions of limited financing, it is necessary to understand how justified from an economic point of view is its use. In the work of Rudakova A.V. The analysis of the “cost -efficiency” of Lisinopril in various clinical situations was carried out [3]. The study shows that lysinopril is characterized not only by high clinical efficiency in patients with arterial hypertension, heart failure, diabetes, lesion of target organs, and in the early postinfarct period, demonstrated in large -scale controlled tests (Allhat, Atlas, Gissi - 3), but and high cost efficiency in these clinical situations. Thus, Lizinopril (diroton) is one of the reference inhibitors of the ACE, the effectiveness and safety of which gives grounds for the wider use of the drug in the practice of the therapist.

Literature 1. Balabolkin M.I., Klebanova E.M., Kreminskaya V.M. Modern issues of classification, diagnosis and compensation criteria for diabetes mellitus. Diabetes mellitus, 2003, No. 10, p.5. 2. Ivleva A.Ya. Clinical use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II antagonists. M., 1998, from Miklos. - With. 158 3. Rudakov A.V. Lisinopril in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases: pharmacoeconomic aspects. Clinical gerontology. – 2003 – volume 9, no. 7. – pp. 37–42. 4. Preobrazhensky D.V., Sidorenko B.A. The use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. Cardiology – 1997 – vol. 37, No. 3. – pp.100–104. 5. Use of lisinopril for arterial hypertension. Difficult patient /Archive/ No. 3. – 2006. 6. Sidorenko B.A., Preobrazhensky D.V. Treatment and prevention of chronic heart failure. Moscow, JSC “PRESSID”, 1997. – pp. 169–188. 7. Sychev O.S., Getman T.V., Lizogub S.V. Use of lisinopril in patients with cardiac arrhythmias. 8. Tsvetkova O.A. Diagnosis, pharmacotherapy and prevention of pulmonary hypertension in patients with concomitant pathology: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and coronary heart disease. Diss. Doctor of Medical Sciences Moscow – 2004. – p. 177. 9. Ambrossioni E., Borgii S., Magnani V. et al. The effect of the angiotensin–convertmg–enzmie inhibitor zofenopril on mortality and morbidity after anterior myocardial infarction. New Engi J Med. 1995; 332:2:80–85. 10. Andersen NH, Poulsen PL, Knudsen ST et.al. Long–term dual blockade with candesartan and lisinopril in hypertensive patients with diabetes: the CALM II study. Diabetes Care. 2005 Feb;28(2):273–7]. 11. Anichkov DA, Shostak NA, Schastnaya OVComparison of rilmenidine and lisinopril on ambulatory blood pressure and plasma lipid and glucose levels in hypertensive women with metabolic syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005 Jan; 21(1):113–9. 12. Arnett DK, Davis BK, Ford CE, Boerwinkle E, Leiendecker–Foster C, Miller MB, Black H, Eckfeldt JH. Pharmacogenetic study of the relationship between polymorphisms (insertion/deletion) of ACE and blood pressure or cardiovascular risk in relation to antihypertensive therapy: Study of the genetics of therapy associated with hypertension.Circulation. 2005. Jun 28;111(25):3374–83. 13. Davis BR, Culter JA, Gordon DJ Antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial. Am. J. Hypertens. – 1996. –Vol.9. –P.342–60. 14. Diamant M, Vincent HH Lisinopril versus enalapril: evaluation of through:peak ratio by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens. – 1999/ – Jun;13(6):405–12. 15. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Soprawivenza nell'infarto Miocardico. GISSI–3: effects oftisinopril and transdermal glyceryl trinitrate singly and together on 6–week mortality. 16. Jensen HAEfficacy and tolerance of lisinopril compared with extended release felodipine in patients with essential hypertension. Danish Cooperative Study Group. Clin Exp Hypertens A. – 1992. – 14(6):1095–110. 17. Landmark K, Tellnes G, Fagerthun HE et al. Treatment of hypertension with the ACE inhibitor lisinopril. A multicenter study of patients with mild to moderate hypertension in general practice. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. – 1991. Oct 30;111(26):3176–9. 18. Latini R., Maggioni AP ACE inhibitor use in patients with myocardial infarction. Summary of evidence from clinical trials. Circulation. – 1995; 92:10:3132–3137. 19. Major Outcomes in High–Risk Hypertensive Patients Randomized to Angiotensin–Converting Enzyme Inhibitor or Calcium Channel Blocker vs Diuretic. The Antihypertensive and Lipid–Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. – 2002; 288:2981–97. 20. Malacco E, Santonastaso M, Vari NA et al. Comparison of valsartan 160 mg with lisinopril 20 mg, given as monotherapy or in combination with a diuretic, for the treatment of hypertension: the Blood Pressure Reduction and Tolerability of Valsartan in Comparison with Lisinopril (PREVAIL) study. Clin Ther. – 2004. – Jun;26(6):855–65. 21. Motero Carrasco J. A comparative study of the efficacy of lisinopril versus quinapril in controlling light to moderate arterial hypertension. A follow-up with ABPM. Rev Esp Cardiol. – 1995, Nov;48(11):746–53. 22. Os I, Bratland B, Dahlof B at al. Lisinopril or nifedipine in essential hypertension? A Norwegian multicenter study on efficacy, tolerability and quality of life in 828 patients. J Hypertens. – 1992, Feb;10(2). 23. Packer M., Poole–Wilson P., Armstrong P. et al. Comparative effects of low-dose versus high-dose lisinopril on survival and major events in chronic heart failure: the Assessment of Treatment with Lisinopril And Survival (ATLAS). Europ. Heart J., 1998; 19 (suppl.): 142 (abstract). 24. Rosei EA, Rizzoni D, Comini S et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and tolerability of nebivolol versus lisinopril in the treatment of essential arterial hypertension: a randomized, multicentre, double-blind study. Blood Press Suppl. – 2003, May;1:30–5 25. Stergiou GS, Efstathiou SP, Roussias LG et. Al. Blood pressure– and pulse pressure–lowering effects, through:peak ratio and smoothness index of telmisartan compared with lisinopril. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. – 2003, Oct;42(4):491–6. 26. Weir MR, Reisin E, Falkner B Nocturnal reduction of blood pressure and the antihypertensive response to a diuretic or angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor in obese hypertensive patients. TROPHY Study Group. Am J Hypertens. – 1998, Aug;11(8 Pt 1):914–20. 27. Wu SC, Liu CP, Chiang HT et al. Prospective and randomized study of the antihypertensive effect and tolerability of three antihypertensive agents, losartan, amlodipine, and lisinopril, in hypertensive patients. Heart Vessels. – 2004, Jan;19(1):13–8.

What is lisinopril prescribed for?

The name of the drug suggests that it belongs to the so-called group of “by-catch”, the action of which is primarily aimed at lowering blood pressure in the fight against hypertension. However, a doctor may prescribe treatment with Lisinopril in other cases:

- for chronic heart failure;

- in acute myocardial infarction not accompanied by arterial hypotension;

- to combat nephropathy of diabetic etiology, both type 1 and type 2.

- with arterial hypertension.

Self-administration of the drug is unacceptable. The dose, frequency of doses and duration of treatment are determined only by the doctor.

conclusions

Lisinopril is a long-acting ACE inhibitor that is highly effective. The drug is considered the “gold standard” in the treatment of hypertension and circulatory failure (together with diuretics, statins, angiotensin-II antagonists and Ca2+ channel blockers). The combined use of Lisinopril and Indapamide reduces the likelihood of recurrent episodes of ischemic stroke by 29% and intracranial hemorrhage by 50%.

It is worth remembering that the antihypertensive effect reaches a plateau no earlier than 10-14 days from the start of treatment.

Before using the drug, you must carefully read the instructions! Lisinopril should not be taken without a doctor’s prescription, and you should not replace it with an analogue yourself.

Contraindications to the use of Lisinopril

Contraindications to the use of Lisinopril are pregnancy and breastfeeding. If the expectant mother suffers from hypertension, her condition is monitored in a hospital setting. High blood pressure in such cases is corrected with safe doses of diuretics.

If replacing the drug during breastfeeding is not possible, you should definitely transfer the child to artificial feeding or feeding with donor milk.

Other contraindications are:

- excess potassium in the blood;

- renal dysfunction;

- gout;

- renal artery stenosis;

- elderly age;

- cerebrovascular insufficiency;

- hypotension;

- childhood;

- tissue obstruction that interferes with normal outflow;

- availability of a donor kidney.

Lisinopril: instructions for use

The drug is taken once a day. It is important to observe the time interval between medication doses. Superimposing the effect of one dose on another threatens severe hypotension, up to loss of consciousness.

If the first tablet was taken at lunch, then the second tablet should not be taken in the morning hours of the next day. It is important to keep taking your medication at lunchtime.

A single dose is prescribed by the attending physician based on the following studies:

- blood pressure conditions;

- heart function;

- vascular health;

- risk factors.

If an increase in the single dose is not required, as a rule, a single dose of 2.5 mg of Lisinopril is sufficient to normalize the patient's condition. Dose adjustments can be made no earlier than after 4 weeks of continuous use of the drug, since it is after this time that the maximum possible therapeutic effect is achieved.

If increasing the dose does not give the required result, a similar drug from a different pharmacological group is prescribed, the action of which in a different way will help normalize blood pressure.

If treatment of an insulin-dependent patient is required, Lisinopril is taken under the strict supervision of a specialist in a hospital setting.