Thrombosis of arteries and veins of the intestine is called “mesenteric” after the name of the vessels. Most often it is a complication of acute myocardial infarction, an attack of atrial fibrillation, or slow sepsis. Mesenteric thrombosis usually affects the superior mesenteric artery. Much less often it is found in the inferior artery and mesenteric veins.

Elderly and senile people are prone to the disease. As a result of blocking of the vessel, arterial or venous insufficiency of the intestinal section occurs, which leads to malnutrition and further infarction of the wall.

Thrombosis in veins is less common than in mesenteric arteries. The mixed form, in which blockage of both veins and arteries occurs, is rarely observed in very advanced cases.

The disease is difficult to diagnose. 1/10 of deaths from intestinal infarction occur in people under 40 years of age. Women are more susceptible to this type of pathology than men.

In the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), embolisms and thromboses of the iliac artery are coded I 74.5 and are included in the zonal group of pathology of the abdominal aorta. Venous mesenteric thrombosis is a component of acute vascular diseases of the intestine and has code K55.0.

Introduction

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is a life-threatening vascular disease that often requires immediate surgical treatment. Early diagnosis and immediate intervention that restores mesenteric blood flow prevents intestinal necrosis and patient death. The cause of AMI can be different, and the prognosis depends on the depth of pathological changes [1, 2].

The severity of progression depends on the pathogenesis of AMI and the choice of treatment; diagnosing this pathology remains a challenge for the clinician. Early diagnosis and effective treatment are primary for improving clinical outcomes; any delay in diagnosis leads to an increase in mortality to 59-93% [2]. Although mesenteric angiography remains the gold standard for diagnosing mesenteric ischemia, it is not applicable in many situations [3]. Laparoscopy is increasingly used to diagnose various diseases, although its role in the early diagnosis of AMI remains controversial.

External examination of the wall of the small intestine is the only thing that allows us to indirectly judge ischemic changes in the mucous and submucosal layer in the early stages of AMI [4]. However, in some situations, the role of diagnostic laparoscopy (DL) may be discussed as an addition to the clinical examination and choice of treatment for patients with AMI. Critically ill patients are one group where laparoscopy may be particularly valuable. In addition, DL can be performed directly at the bedside of a non-transportable patient [5].

Arterial embolism

Arterial embolism is the most common form of AMI, it is observed in 40-50% of cases [6]. Many mesenteric emboli have their source in the heart cavity. Myocardial ischemia or infarction, atrial tachyarrhythmia, endocarditis, cardiomyopathies, ventricular aneurysms, valve diseases - all these conditions are risk factors for the development of mural thrombosis. Many arterial emboli enter the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). While 15% of arterial emboli remain at the ostium of the SMA, 50% penetrate more distally into the middle colic artery, which is the first major branch from the SMA. The onset of symptoms is usually dramatic, as a consequence of insufficient development of collaterals [7]. Often, diagnosis of SMA embolism is possible only intraoperatively, based on visualization of small bowel ischemia. Because most SMA emboli travel distally into the middle colic artery, the anatomy allows the inferior pancreaticoduodenal vessels to provide reperfusion to the proximal jejunum while the remainder of the small bowel is subject to ischemia or infarction.

Arterial thrombosis

Acute mesenteric thrombosis accounts for 25-30% of all cases of ischemia. Almost all of them are associated with severe atherosclerosis developing at the origins of the SMA. The blood supply to internal organs in this situation is maintained due to the development of collaterals. Ischemia or infarction of the small bowel occurs when the last visceral vessel or important collateral becomes occluded. The extent of ischemia or infarction in this case is greater than with embolism and extends from the duodenum to the transverse colon.

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia

Approximately 20% of mesenteric ischemia is non-occlusive. The pathogenesis of nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NMI) is not entirely understood but is often associated with low cardiac output associated with diffuse mesenteric vasoconstriction. Vasoconstriction of splanchnic organs is a response to hypovolemia with decreased cardiac output and hypotension. As a result of insufficient blood flow, intestinal hypoxia occurs, which inevitably leads to intestinal necrosis. Conditions predisposing to NMI include age over 50 years, myocardial infarction, heart failure, liver and kidney disease, and major abdominal or cardiovascular surgery. However, these patients may not have risk factors. This condition often develops in patients in critical condition with a host of concomitant diseases; NMI often begins unexpectedly and results in high mortality.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of thrombosis has been studied and is well described by Virchow's triad. The main links in thrombus formation are: damage to the vascular endothelium, changes in blood flow and hypercoagulation (violation of the rheological properties of blood), the development of each of which has its own reasons.

The formation of intravital blood clotting in a vessel occurs in several stages and includes platelet agglutination, fibrinogen coagulation, erythrocyte agglutination and precipitation of plasma proteins.

Mesenteric venous thrombosis

Mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) is the rarest type of mesenteric ischemia, accounting for 10% of AMI [8]. It can develop secondary to any intra-abdominal disease (tumor, peritonitis, pancreatitis), or as a result of a primary blood clotting disorder, and only in 10% of cases MVT is classified as idiopathic. MVT is usually segmental in nature with edema and hemorrhages in the intestinal wall. Thrombi usually arise in the venous arcades and spread further into larger vessels. Hemorrhagic infarction occurs in cases where intramural vessels are blocked. The thrombus can usually be palpated in the superior mesenteric vein. Involvement of the inferior mesenteric vein and colonic vessels is rare. The transition of the unchanged intestinal wall to the ischemic zone with venous thrombosis occurs more smoothly than with arterial embolism or thrombosis.

Causes

The immediate causes of a blood clot in the vascular bed of the mesentery are changes in the vascular walls against the background of slow blood flow and increased blood clotting. Indirect causes of the development of a blood clot in the arterial bloodstream of the intestine are: chronic heart failure , hypercoagulable processes , cardiosclerosis , endocarditis , vascular atherosclerosis , pancreatitis , trauma .

The causes of intestinal thrombosis in the venous vessels of the intestine are mechanical (strangulation of the mesentery, adhesions, volvulus), closed abdominal trauma with damage to the mesenteric veins/intestinal contusion, blood diseases (thrombocytosis), hemodynamic disorders, increased intra-abdominal pressure, taking oral contraceptives, portal hypertension , malignant neoplasms, destructive forms of pancreatitis , appendicitis , cholecystitis cardiac decompensation , taking hormonal drugs, Crohn's disease , ulcerative colitis , intra-abdominal infections of the abdominal organs, abscesses .

Diagnosis

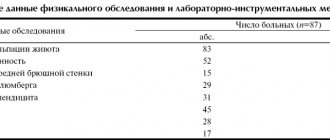

Many signs and symptoms associated with AMI also occur with other intra-abdominal pathologies, such as pancreatitis, acute diverticulitis, acute intestinal obstruction, and acute cholecystitis. In general, patients with SMA embolism or thrombosis have an acute onset of the disease, rapid development of symptoms, and rapid deterioration of the condition, while with MVT and NMI the clinical picture develops more smoothly. With SMA embolism, the increase in symptoms occurs at lightning speed due to the lack of collateral blood supply and manifests itself in the form of severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Dehydration, impaired consciousness, tachycardia, tachypnea and circulatory collapse are rapidly increasing. Laboratory data show metabolic acidosis, leukocytosis, blood concentration.

AMI can rapidly progress to intestinal infarction; timely diagnosis and treatment are of strategic importance [1, 9]. A high level of suspicion based on history and initial examination data serves as the cornerstone in the diagnosis of acute intestinal ischemia. When diagnosis is made on the first day, survival rate is 50%, and when it is delayed it drops to 30% or lower. Laboratory studies often show hemoconcentration, leukocytosis, and metabolic acidosis. High levels of amylase, aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, and creatinine phosphokinase are often found in test results, but they are not sensitive or specific for diagnosis. Hyperphosphatemia and hyperkalemia occur later and often accompany intestinal infarction.

Radiation examination of the abdominal cavity is also nonspecific. In the initial stage of the disease, 25% of patients may have normal radiological data. Characteristic radiographic changes, such as thickening or compaction of the intestinal wall, are less common than in 40% of patients. Air in the portal vein is a late symptom and is associated with a poor prognosis. At a high level of suspicion for AMI, CT is more likely to clarify specific details. Some authors report a sensitivity of 93.3% and a specificity of 95.9% for CT scans with IV contrast [3, 9].

Thickening of the intestinal wall, intramural hematoma, dilated and fluid-filled intestinal loops, congestion of the mesenteric vessels, pneumatosis, gas in the mesenteric and portal veins, infarction of other organs, arterial and venous thrombosis may be visible on CT scanning. The value of the study increases in the absence of indications for immediate laparotomy for suspected AMI. Early angiography increases the chances of survival.

Mesenteric angiography allows the differentiation of embolism and thrombotic arterial occlusion. An embolus most often occludes the middle colic artery, the first major branch of the SMA. Thrombotic disease most often affects the source of the SMA, and the vessel is not visualized at all. MVT is characterized by a generalized slowing of arterial blood flow. Usually the lesion is segmental in nature, in contrast to NMI, when normal venous outflow is preserved [3, 9].

Symptoms of chronic course

The development of the clinical picture depends on the extent of the aortic lesion. When its lumen is closed by only ten percent, the general blood supply system begins to support additional collateral blood flow. Therefore, there are no visible manifestations, which makes diagnosis difficult.

The first symptoms appear when there is a long-term lack of blood supply. In this case, the intestines, kidneys and lower limbs suffer. Each form of pathology has its own symptoms. Intestinal ischemia manifests itself as follows:

- After a heavy meal, a sharp pain occurs in the stomach, which simultaneously radiates to the lower back, back of the head and left side of the chest. It goes away on its own two to three hours after eating.

- The patient suffers from tract dysfunction syndrome. Periodically, a feeling of heaviness and fullness occurs, mild nausea develops, diarrhea alternates with constipation, vomiting brings obvious relief. In this state, the patient consciously begins to refuse food, and therefore quickly loses weight.

- In the area of the duodenum, the formation of a secondary ulcer is possible.

- Against the background of these dysfunctions, asthenia develops. It is expressed in the form of weakness, decreased performance.

- Depression gradually sets in.

Renal ischemia is characterized by a persistent increase in blood pressure. The tonometer shows more than 140/90 mmHg. This condition is dangerous because it can cause a heart attack or stroke.

- Aneurysm of the ascending aorta: treatment, surgery, cost

If the patient complains of burning pain in the calves, buttocks, lower back, numbness in the foot, coldness of the legs, and at the same time intermittent claudication occurs, partial closure of the lumen of the abdominal aorta in the area of transition to the iliac arteries can be suspected.

Laparoscopy: an alternative diagnostic procedure

Although CT is recognized as a radiological test with high sensitivity, it is limited in many situations [10]. Patients with mesenteric ischemia often suffer from chronic venous insufficiency and heart disease, which preclude the use of IV contrast. In addition, severe dehydration and acidosis are often present in these patients, requiring prolonged correction and delaying treatment. Such a pause is highly likely to lead to irreversible changes in the intestines. Laparoscopy can be an alternative to other traditional methods. In addition, unstable patients require constant intensive care, and laparoscopy can be performed directly at the patient's bedside, which is extremely important for early diagnosis.

What are external hemorrhoids? A little anatomy

External hemorrhoids (plexuses) are formations located under the skin on the border of the anal canal and perianal (around the anus) skin. They are venous plexuses (Fig. 3). Usually they do not manifest themselves in any way, are not visible and cannot be detected by touch. As the condition worsens chronically

changes occur in internal hemorrhoids and in external hemorrhoids, leading to their enlargement and loss of connection with the muscular ring of the anal canal. However, the most significant changes in the external nodes occur when a blood clot occurs in them.

Rice. 3. Diagram of the anal canal, at the exit of which the external hemorrhoids are located (number 7 in the diagram).

Limitations of laparoscopy in the early diagnosis of AMI

Emergency laparoscopy can be used to diagnose and treat some forms of acute abdomen. DL is also indicated in clinically unclear situations and for staging the oncological process.

Data on the effectiveness of DL for mesenteric ischemia are contradictory [4, 10, 11]. Limitations are associated with questionable intraoperative data in the early stages of ischemia. It is well known that at the beginning of the development of AMI, primary changes occur in the inner layers of the intestinal wall (mucosal and submucosal layer). Laparoscopy performed at this stage may not detect changes, since the serous surface is often intact. The inability to palpate the mesentery to assess pulsation is another disadvantage of laparoscopy in diagnosing AMI [4, 10-13].

However, other important signs of intestinal ischemia such as edema, hyperemia, focal hemorrhages, dark effusion or visible gangrene can be detected during laparoscopic examination of the intestine. Experimental studies performed in pigs have opened up additional possibilities for laparoscopy in terms of interpreting intraoperative data in the early stages of mesenteric ischemia. The study describes the use of ultraviolet light and the drug fluorescein to identify AMI. This substance makes it possible to identify fluorescent viable tissue from the dark ischemic intestinal wall [14, 15]. Another factor limiting the use of laparoscopy is the effect of pneumoperitoneum on mesenteric blood flow. High intra-abdominal pressure may reduce venous return with a subsequent fall in cardiac output. High intra-abdominal pressure can also have a direct effect on the aorta and its branches. Therefore, intra-abdominal pressure should not exceed 10-15 mmHg [12]. All this ensures the safety of the DL.

Treatment

Once a diagnosis of AMI is made, treatment should begin immediately. With the exception of NMI, which requires drug therapy, most cases of AMI dictate the need for surgical intervention to restore intestinal blood flow.

The presence of symptoms of peritoneal irritation is more likely to indicate intestinal infarction than ischemia and requires immediate laparotomy. Even in the absence of intestinal necrosis, surgery is usually necessary to exclude irreversible changes in the intestinal wall. Resection of ischemic bowel is the most common surgical procedure for AMI. Satisfactory arterial pulsation, good blood supply to the remaining segment and the absence of peritonitis dictate the indications for primary anastomosis.

Intra-abdominal contamination, questionable blood supply to the preserved segment of the intestine and poor general condition of the patient are contraindications to the imposition of an interintestinal anastomosis. In this situation, removing both ends of the intestine is the safest procedure. In a small number of patients with the occlusive form of AMI, in the presence of reversible changes, an attempt at revascularization is possible. Embolectomy, thrombectomy, endarterectomy, or bypass may prevent bowel resection in the early stages of AMI. Massive extended gangrene of the intestine is not subject to surgical treatment, since it does not lead to an improvement in the patient’s condition [3, 9].

Forecast

Mesenteric thrombosis, according to clinical studies, is observed much more often than the number of cases diagnosed. This pathology is masked by various acute conditions: cholecystitis, renal colic, appendicitis. The limited time for diagnosis does not always allow the disease to be detected.

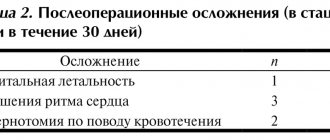

Fatal cases, according to pathologists, are 1–2.5% of hospital mortality. These are thrombosis in the stage of infarction and diffuse peritonitis. Late surgery (after 12 hours) means high mortality (up to 90%).

A good prognosis for recovery with surgical treatment of chronic thrombosis in the first two stages. Timely seeking surgical help for abdominal pain allows the patient to be operated on in a favorable time frame and prevent perforation of the intestinal wall.

The role and place of laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is a quick and easy procedure. The speed of execution of DL is one of its advantages, which should not be underestimated when a decision needs to be made immediately. In patients in serious condition, laparoscopy is effective and safe [3]. Acute abdomen due to acidosis may occur in some cases; DL helps in differential diagnosis. It is convenient to perform it at the bedside of a seriously ill patient requiring intensive hemodynamic and respiratory treatment. The advantages of the method are the absence of the need to transport a seriously ill patient, quick diagnosis, elimination of auxiliary tests and low cost.

Jaramillo et al. [5] conducted a retrospective study in the intensive care unit of the Texas Institute of Endosurgery, which showed the feasibility and safety of performing laparoscopy at the patient's bedside over a period of 13 years. The study included 13 patients with an average age of 75.5 years. All of them were on mechanical ventilation under sedation. DL was easily performed under local anesthesia and IV sedation. Pneumoperitoneum was created with a Veress needle followed by an intra-abdominal pressure of 8-10 mmHg. The average duration of the procedure is 35 minutes. 46% of them had mesenteric necrosis, and all of them died within 48 hours without any additional procedures. Another 30% of patients had negative DL, 1 had fecal peritonitis and died within 24 hours. The remaining 15% were found to have acute acalculous cholecystitis.

Another potential area for the use of laparoscopy to diagnose AMI is in intensive care unit patients. Abdominal complications are a serious problem in the early postoperative period in patients undergoing major cardiac surgery using extracorporeal circulation. In this case, the mortality rate reaches 70%. Early diagnosis and timely treatment are an important factor determining the outcome. However, clinical examination of the abdomen is difficult in these patients [5].

A study conducted at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, showed the accuracy of laparoscopy in identifying abdominal complications in patients after cardiac surgery. DL was performed in 17 patients. No pathology was found in one. In 6 out of 17, ischemia of the right half of the colon was detected; in 5 out of 17, massive expansion of the colon without ischemia was detected, which was confirmed by laparotomy. 3 developed acute cholecystitis, confirmed by transection. In one case, fibrinous peritonitis without a primary focus was discovered during DL, which was confirmed by laparotomy. And only in one case was DL false-negative; laparotomy revealed pancreatic necrosis [16].

Second-Look

In 1921, Cokkins [17], who described AMI, stated that the diagnosis of this disease was impossible, the prognosis was hopeless, and treatment was pointless. Despite progress in diagnosis, surgical and non-surgical treatment, and intensive care, mortality in AMI remains high. Most researchers report a mortality rate of 59–93% [4, 11]. The lack of pathognomonic symptoms and their late recognition limit therapeutic measures to, at best, bowel resection. But even after this, ischemia of the remaining intestine can progress. In mesenteric venous thrombosis, after resection of a necrotic loop and administration of anticoagulant therapy, thrombosis can progress further from the ischemic segment [13].

In 1965, Shaw [18] proposed second-look laparotomy to overcome difficulties in assessing the adequacy of bowel resection. Originally recommended for assessing the condition of anastomoses, second-look has found widespread use in our time. This is especially important for determining the viability of the remaining intestinal segment after surgery for AMI. However, the timing of second-look is uncertain, especially in patients with intestinal anastomoses. In most cases, anastomotic failure occurred on days 3-5; second-look laparoscopy made it possible to timely identify this complication and prevent peritonitis. Excluding early intra-abdominal complications, the optimal period for performing second-look laparoscopy is 48-72 hours after the first operation [19].

What will happen after the operation?

Typically, patients feel dramatic relief after surgery and note a decrease in pain (Fig. 6). Sometimes continued minimal pain therapy is required. The main task of the patient in the postoperative period is to normalize stool: soft stool causes much less pain during bowel movements than dense stool. As a rule, patients return to their normal lives 2-3 days after surgery, sometimes the very next day.

a) b)

Rice. 6. View of the anus before (a) and immediately after removal of the external hemorrhoid (b). Before the operation, the patient rated the pain level as 8 out of 10, immediately after the operation it was 4 out of 10.

Second-look laparoscopy

This procedure is increasingly replacing open second-look surgery as it reduces surgical and anesthetic trauma. Anadol et al. [22] compared open and laparoscopic second-look in patients with mesenteric ischemia. In the first group (n=41), repeat laparotomy was performed in 23 patients. In the second group (n=36), a 10 mm trocar was left until the laparotomy wound was sutured and a second-look was performed using a laparoscope in 23 patients. 16 laparotomies in the first group (70%) were in vain. Two patients (8%) in the laparoscopic group required repeat resection, whereas 20 (87%) did not require laparotomy. The authors decided that patients with mesenteric ischemia already suffer enough and deserve minimally invasive endoscopic surgery [22].

Second-look laparoscopy is described as a safe method for determining intestinal viability, reducing the risk of complications and allowing a quick determination of treatment tactics. In addition, short and shallow anesthesia minimizes the risk of deterioration in critically ill patients. At the same time, mortality is reduced due to shortening the duration of the operation [5, 19, 20].