Therapist

Berezhko

Olga Igorevna

35 years of experience

General practitioner of the highest category, member of the Russian Scientific Medical Society of Therapists

Make an appointment

Vasculitis is a group of vascular diseases that are characterized by the development of an inflammatory process and subsequent necrosis of the vascular walls. The disease is also called arteritis or angiitis. As the disease progresses, a significant deterioration in blood circulation occurs. Pathology can affect arteries, veins, capillaries, venules and arterioles.

Types and classification of vasculitis

Vasculitis is divided into types:

- primary;

- secondary;

- systemic.

In the first case, we are talking about an independent and still just beginning disease. The second type may appear with other pathologies, for example, tumors. It can also occur as a reaction to an infection. Systemic vasculitis can occur in different ways. It leads to inflammation of blood vessels and damage to their walls, and tissue necrosis cannot be ruled out. Without proper treatment, complications usually occur, including death.

Based on the caliber of the affected vessels, a classification of vasculitis was identified. It may be in the form:

- arteritis (affects large vessels);

- phlebitis (affects the walls of the veins);

- arteriolitis (inflames the arteries and arterioles);

- capillaritis (affects capillaries).

Also included in a separate category is vasculopathy, which is characterized by the absence of clear signs of inflammation and infiltration of the vascular walls.

The degree of vascular damage can be mild, moderate and severe.

Overdiagnosis of systemic vasculitis

Inflammation of the wall of blood vessels is an integral symptom of vasculitis, which is found in all patients without exception.

However, there are also other types of errors associated with overdiagnosis of primary vasculitis. Among clinicians with little practical knowledge of vasculitis, there is a tendency to call “systemic vasculitis” (especially often “polyarteritis nodosa” and “hemorrhagic vasculitis”) any unclear condition when the patient has a prolonged fever and has one or another set of nonspecific symptoms. Very often in such situations, the diagnosis seems to be proven by a skin biopsy - an examination of an excised area of skin and subcutaneous tissue under a microscope, revealing vascular inflammation. However, this research method does not reliably distinguish between primary systemic vasculitis and secondary (symptomatic) vasculitis.

Causes of the disease

The reasons for the formation of primary vasculitis are still unknown to science. Secondary disease can occur against the background of:

- acute or chronic infection;

- genetic (hereditary) predisposition;

- thermal effects (overheating or hypothermia of the body);

- various injuries;

- burns;

- contact with chemicals and poisons.

Another cause of vasculitis can be viral hepatitis. One or more risk factors are enough to change the antigenic structure of tissues. In this case, the immune system begins to secrete antibodies, which further damage the tissue, in this case the blood vessels. This leads to an autoimmune reaction and inflammatory and degenerative processes.

Consequences and complications

If the disease is not treated on time, the following complications may occur:

- liver and kidney failure;

- abdominal abscesses

- pulmonary hemorrhage;

- intussusception;

- polyneuropathy.

If, as the disease progresses, part of a blood vessel stretches and dilates, the risk of an aneurysm .

If during the inflammatory process the vessels narrow, the blood supply to individual organs and tissues may stop, which increases the likelihood of necrosis.

Symptoms of vasculitis

Regardless of the type and form of the disease, the symptoms of vasculitis are similar. These include:

- decreased body temperature;

- joint pain;

- pale skin;

- regularly recurring sinusitis;

- vomiting;

- nausea;

- myalgia;

- rash in the form of spots, urticaria, subcutaneous nodules, hemorrhagic purpura, ulcers or blisters;

- sudden mood swings;

- convulsions;

- intoxication;

- drowsiness;

- sometimes pleurisy, bronchial asthma;

- loss of sensation (insemination);

- exacerbation of cardiovascular diseases;

- weakness;

- lack of appetite followed by weight loss.

Depending on the location, vasculitis can also manifest itself through a sharp deterioration in vision, inflammation and swelling of the eyes, pain in the lower back, in the kidney area, abdominal cramps and disruption of the gastrointestinal tract.

Are you experiencing symptoms of vasculitis?

Only a doctor can accurately diagnose the disease. Don't delay your consultation - call

Diet

Hypoallergenic diet

- Efficacy: therapeutic effect after 21-40 days

- Timing: constantly

- Cost of products: 1300-1400 rubles. in Week

During illness, it is important to exclude from the diet all foods that can provoke allergic reactions. It is necessary to completely remove chocolate, cocoa, eggs, and citrus fruits from the diet. If you have kidney failure, you should not eat too salty foods or foods containing a lot of potassium. Alcohol should be completely avoided and food should not be too cold or too hot.

It is important to adhere to the following recommendations:

- Eat in small portions and at least 6 times a day.

- Introduce foods containing vitamins C, B, K and A into your diet.

- The amount of salt per day should not exceed 8 g.

- It is important to eat plenty of fermented milk products to restore calcium reserves in the body.

- The menu should include vegetable soups, boiled vegetables, cereals with milk and regular ones, vegetable oils, sweet fruits, boiled meat and fish, white bread crackers.

- You need to drink green tea, herbal infusions, jelly and compotes.

- As you recover, the diet is adjusted.

Diagnostics

It is necessary to try to diagnose vasculitis even in the presence of the very first signs. The disease is serious and dangerous and requires immediate treatment.

If you suspect an illness, you must perform a series of examinations and tests. Appointed:

- angiography;

- general blood and urine tests;

- ECHO-cardiography;

- blood biochemistry;

- Ultrasound of the heart, abdominal organs and kidneys;

- X-rays of light.

The problem is that it is very difficult to diagnose vasculitis in the early stages. But more striking signs of the disease and a reason to sound the alarm appear even when several organs are affected at once.

In severe and rapid progression of the disease, an additional biopsy is performed, followed by a detailed study of tissue samples.

Forecast

The prognosis of vasculitis depends on its type and the degree of damage to surrounding organs and tissues. To treat this disease, it is very important to make a correct diagnosis in time and prescribe the correct drug treatment that does not cause allergic reactions and side effects.

Thanks to high-quality, adequate treatment, the life expectancy of patients increases significantly. If treatment was started on time, the five-year survival rate is 90%. When therapy is absent for a long time, this figure drops to 5%. Patients often become disabled.

Damage to the kidneys, brain, aorta, coronary vessels, and digestive system organs worsens the prognosis. Vasculitis is more severe in people over 50 years of age. Therefore, people with vasculitis need to closely interact with their doctor and strictly follow all his recommendations.

Author of the article:

Mochalov Pavel Alexandrovich |

Doctor of Medical Sciences therapist Education: Moscow Medical Institute named after. I. M. Sechenov, specialty - “General Medicine” in 1991, in 1993 “Occupational diseases”, in 1996 “Therapy”. Our authors

Treatment of vasculitis

Treatment of vasculitis is prescribed depending on the type of organs affected and concomitant diseases. If the primary form of the disease appears against the background of an allergy, it usually disappears on its own and does not require additional measures.

If the source of the disease affects vital organs, such as the heart, brain, kidneys or lungs, then the patient is prescribed a course of intensive therapy.

To stabilize blood circulation, treatment can be carried out both at home and in a hospital setting. Pregnant women, children and patients with severe forms of the disease are required to be hospitalized.

Use:

- chemotherapy;

- corticosteroids;

- NSAIDs;

- anticoagulants;

- enterosorbents;

- antiplatelet agents;

- antihistamines;

- cytostatics.

Additionally, plasmapheresis, hemosorption and immunosorption are included.

Treatment with folk remedies

If you visit any thematic forum, you can learn about many methods of treating vasculitis using traditional methods. But it is always important to remember that such treatment methods are only auxiliary in the process of main therapy. Before using them, it is better to consult a doctor about the advisability of such actions.

- If it is necessary to treat superficial vasculitis, herbal preparations are used that have a positive effect on the permeability of vascular walls and produce an anti-inflammatory effect. This effect is possessed by: Japanese sophora, buckwheat, water and bird knotweed, horsetail, and nettle.

- The use of decoctions and infusions of herbs that produce a general stimulating effect is also indicated: oat grains and straw, yarrow, rowan and black currant leaves, rose hips.

- The following will help reduce swelling in deep forms of vasculitis: string, stinging nettle, and cinquefoil erecta.

- In order to stimulate the function of the adrenal cortex, which is important in severe forms of vasculitis, treatment with drugs and decoctions containing ginseng, black elderberry, and eleutherococcus is recommended. Often patients are prescribed alcoholic infusions of ginseng and eleutherococcus.

- It is also recommended to drink green tea, which strengthens the walls of blood vessels and reduces their permeability, and also has a positive effect on metabolic processes in the body. It should be drunk every day, alternating with other herbal teas.

The following herbal remedies can be used:

- First collection. Knotweed, stinging nettle, sophora thick-fruited - 4 parts each, yarrow - 3 parts, black elderberry - 1 part. The infusion is prepared by pouring 5 g of the mixture with 1 cup of boiling water. Drink half a glass twice a day.

- Second collection. Black elderberry, horsetail - 3 parts each, peppermint - 2 parts. The infusion is prepared by pouring 5 g of the mixture with 1 cup of boiling water. Drink the infusion warm, half a glass 4 times a day. This infusion is also used for lotions. Applications are applied to the affected areas and kept for 15 minutes. This procedure can be carried out several times a day.

- The third gathering. is used as a general tonic and provides the body with vitamin K. To prepare it, St. John's wort, plantain, lungwort, black currant and rose hips are mixed in equal proportions. 10 g of product should be poured into 1 tbsp. water and boil for a few minutes. Drink half a glass 2 times a day.

Products for external use:

- Compresses made from pine resin. They are applied to the affected areas when applied to the skin. To prepare the product, 200 g of resin must be melted and added to it 40 g of unrefined vegetable oil, 50 g of beeswax. Mix everything, and when the mixture has cooled, apply it to the affected areas without removing it for 24 hours.

- Birch buds and nutria fat. To prepare the product you need to take 1 tbsp. grated dry or fresh birch buds and mix them with 500 g of nutria fat. Leave the product in a clay container for a week, keeping it on low heat in the oven for 3 hours every day. Place in jars and use every day as an ointment.

FAQ

What is the prognosis for vasculitis?

With timely consultation with a doctor, patient survival is 90%.

Is it possible to treat vasculitis at home?

If the patient’s condition and the identified stage of disease development allows this, then it is possible. Only the most difficult cases are hospitalized. Others can take medications on their own.

If you suspect vasculitis, who should you turn to for help?

First of all, you should make an appointment with a therapist, who, after collecting an anamnesis, will refer the patient to specialized specialists: a vascular surgeon, cardiologist, hematologist, etc.

What is vasculitis?

Vasculitis is the general name for a group of diseases characterized by inflammation and destruction of the walls of blood vessels. Typically, the disease affects several tissues or organs: the narrowing of damaged vessels disrupts the blood supply to the organs and causes the death of the tissues supplied to them. The disease can occur in any organ.

If the patient does not receive treatment, vasculitis will not stop progressing. This will lead to damage to various tissues and organs. A person may become disabled or even die.

Vasculitis is a systemic disease affecting connective tissue. Rheumatologists treat pathology. If the need arises, the patient is referred to an infectious disease specialist and a dermatologist.

Both men and women suffer from vasculitis equally. Most often, the disease is diagnosed in children and the elderly. Pathology is gaining momentum. Every year the number of people with vasculitis increases. Scientists attribute this to the uncontrolled and unjustified use of immunomodulatory drugs, as well as to the deterioration of the environmental situation in the world as a whole.

Content:

3. Symptoms of the disease

The unpredictable nature of the occurrence of vasculitis makes its symptomatic picture very vague and diverse. And yet it is possible to identify the relationship between the signs of vasculitis and its location. For example, if skin damage occurs with vasculitis, then its symptom will be a specific rash. If there is a disruption in the blood supply to any part of the nerve, then a sign of this pathological process will be muscle weakness and loss of sensitivity. A stroke indicates a violation of the blood supply to the brain, and a heart attack indicates a violation of the blood supply to the heart.

Among the general symptoms of vasculitis, characteristic of all types of this disease, are the following:

- lack of appetite;

- weakness;

- increased body temperature;

- increased fatigue;

- pallor.

Therefore, it is very important to immediately consult a doctor if you notice any unclear symptoms of vasculitis.

About our clinic Chistye Prudy metro station Medintercom page!

The most common forms of pathology:

- Hemorrhagic vasculitis (according to clinical forms, it is divided into cutaneous, abdominal, renal and articular vasculitis). It occurs mainly in childhood and affects mainly small vessels. The main symptoms are a palpable rash (purpura), gastrointestinal and kidney dysfunction, and joint pain.

- Cutaneous vasculitis. It develops exclusively in small and medium-sized vessels of the subcutaneous tissue. It manifests itself as a rash, purpura or ulcers.

- Behçet's disease (Adamantiadis-Behçet). Affects the mucous membranes of the eyes, mouth, genitals and skin. As the disease progresses, ulcers appear on the mucous membranes. In addition, the disease affects the gastrointestinal tract and brain.

Urticarial vasculitis: a modern approach to diagnosis and treatment

Urticarial vasculitis/angiitis (UV) is a skin disease characterized by the appearance of blisters with the histological features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, persisting for more than 24 hours and often resolving with residual effects [1]. The exact prevalence of the disease in Russia and in the world is unknown [2]. Among patients with chronic urticaria, the incidence of HC is 5–20% [3–6]. The pathogenesis of the disease is mediated by the formation and deposition of immune complexes in the walls of blood vessels, activation of the complement system and degranulation of mast cells due to the action of anaphylotoxins C3a and C5a. There are normocomplementary and hypocomplementary forms of HF, as well as a rare syndrome of hypocomplementary HF, which is regarded as a variant of systemic lupus erythematosus [2, 7]. In patients with hypocomplementemia, the disease is usually more severe [8]. All forms of HF, especially hypocomplementary ones, can be accompanied by systemic symptoms (for example, angioedema, pain in the abdomen, joints and chest, uveitis, Raynaud's phenomenon, symptoms resulting from damage to the lungs and kidneys, etc.) [7, 9].

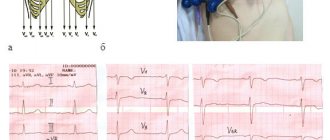

Clinical manifestations

The classic manifestations of HS include blisters (Fig. 1), which are accompanied by burning, pain, tension and, rarely, itching and persist for more than 24 hours (usually 3-5 days, which can be confirmed by circling the rash with a pen or marker and follow-up ). Angioedema (corresponding to the involvement of deep vessels of the skin) occurs in approximately 42% of patients [10], more often in patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome [11]. Giant urticaria (> 10 cm) appear less frequently than in urticaria.

The rashes are localized on any areas of the body, but more often on areas of the skin subject to pressure. When resolved, they leave behind residual hyperpigmentation, which is better determined by diascopy or dermatoscopy.

Systemic symptoms include fever, malaise, and myalgia. Certain organs may be involved: lymph nodes, liver, spleen, kidneys, gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, eyes, central nervous system, peripheral nerves and heart (Table).

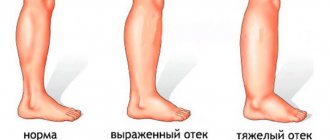

Damage to joints in HF is more common than damage to other organs; appears in half of patients with HF [10] mainly in the form of migrating and transient peripheral arthralgia in the area of any joints, in 50% of patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome [15] - in the form of severe arthritis, which is not typical for normocomplementary HF. Renal involvement usually manifests as proteinuria and microscopic hematuria, defined as glomerulonephritis and interstitial nephritis, and occurs in 20–30% of patients with hypocomplementemia [10]. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchial asthma occur in 17–20% of patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome and in 5% with normocomplementary HF [10]. Possible gastrointestinal symptoms include nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea, which occur in 17–30% of patients with HF [15]. Ophthalmological complications occur in 10% of patients with HF and in 30% of patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome. As a rule, this is conjunctivitis, episcleritis, iritis or uveitis [16].

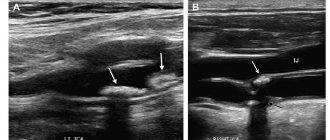

Diagnostics

The examination of patients with HF consists of a history, physical examination, laboratory tests and additional consultations with specialists if necessary (rheumatologist, nephrologist, pulmonologist, cardiologist, ophthalmologist and neurologist). It is important to identify systemic symptoms. To do this, for example, if damage to the respiratory tract is suspected, a chest x-ray, pulmonary function tests and/or bronchoalveolar lavage are performed.

Laboratory tests may include measuring antinuclear antibodies, complement components, and cryoglobulins in the blood, as well as a complete blood count and kidney function tests. ESR is often elevated, but does not serve as a specific indicator and is not associated with the severity of HF or the presence of systemic involvement. Hypocomplementemia, as mentioned earlier, is an important marker of systemic disease and a high likelihood of complications.

Optimal confirmation of EF based on serum complement component measurements requires determination of C1q, C3, C4, and CH50 levels 2 or 3 times over several months of follow-up [17]. Detection of anti-C1q can help in the diagnostic search and confirm the diagnosis of hypocomplementary HC.

Cryoglobulinemia is the most well-known and studied syndrome in some patients with hepatitis C and HC [18]. Cryoglobulins are immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C and are responsible for the development of systemic vasculitis, characterized by the deposition of immune complexes in small and medium-sized blood vessels [18]. These proteins are detected in 50% of HCV-infected individuals, although symptoms associated with cryoglobulinemia are detected in less than 15% of patients [19] and include HF as well as peripheral neuropathy [20]. Treatment is aimed at the underlying HCV infection.

In most cases of HF, the cause of the disease is not determined. Normocomplementary HF acts as an idiopathic disease in many patients, while in others it is associated with monoclonal gammopathy, neoplasia, and sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation or cold [17].

When collecting an anamnesis, it is necessary to clarify the duration of preservation of individual elements, the presence of pain or burning in the area of the rash (itching with urticaria is less common than with chronic urticaria), the presence of residual effects (for example, hyperpigmentation) and associated symptoms. For differential diagnosis and confirmation of diagnosis, a skin biopsy [1] and referral of the patient for consultation with related specialists may be required.

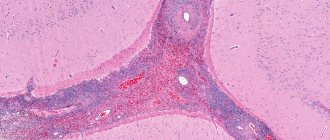

Skin biopsy is the “gold standard” for diagnosing UV. Skin biopsies stained with hematoxylin and eosin usually show the characteristic histopathological features of vasculitis, which include most of the features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis:

- damage and swelling of endothelial cells, destruction or occlusion of the vascular wall;

- release of red blood cells from the vascular bed into the surrounding tissues (extravasation), leukoclasia or karyorrhexis (disintegration of the nuclei of granular leukocytes, leading to the formation of nuclear “dust”), fibrin deposition in and around the vessels, fibrinoid necrosis of venules;

- perivascular infiltration consisting mainly of neutrophils, although in “old” lesions leukocytes and eosinophils may dominate. Sometimes an increase in the number of TCs is observed.

Treatment

HC treatment is selected depending on the presence/absence of systemic symptoms, the extent and severity of the skin process and the previous response to therapy. The goal of therapy is to achieve long-term control using minimally toxic doses of drugs. There is no single standardized approach to treating the disease yet. We tried to systematize the treatment data given below into a single algorithm for practical use (Fig. 2).

Symptomatic therapy

In patients with HC with isolated skin lesions, 1st and 2nd generation antihistamines (especially with severe itching) [13, 15] and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be effective. The main purpose of the latter is to relieve joint pain (effective in no more than 50% of cases). In some patients, NSAIDs lead to exacerbation of heart failure [10]. It is possible to use ibuprofen up to 800 mg 3 or 4 times a day, naproxen 500 mg 2 times a day or indomethacin 25 mg 3 times a day, increasing the dose as needed to a maximum of 50 mg 4 times a day. Taking NSAIDs can cause erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastrointestinal tract and headaches.

Mild to moderate urticarial vasculitis

For the initial treatment of patients with mild or moderate HC in the absence of systemic symptoms and life-threatening manifestations of the disease (for example, kidney and lung damage), as well as in the ineffectiveness of treatment with antihistamines and NSAIDs, glucocorticosteroids (GCS) are used in monotherapy or in combination with dapsone or colchicine . The dose of corticosteroids varies depending on the severity of the heart attack. It is recommended to begin treatment with 0.5–1 mg/kg per day (with a possible dose increase to 1.5 mg/kg per day) with an assessment of response to treatment after 1 week. The effect of therapy in most cases is observed already on days 1–2 of therapy. Once disease control is achieved, the dose of corticosteroids should be gradually reduced over several weeks to the minimally effective dose to maintain CV control.

With long-term therapy with GCS (more than 2–3 months), there is a risk of side effects, which necessitates the addition of steroid-sparing agents to reduce the dose of GCS [10], such as dapsone. The latter has been successfully used as monotherapy or in combination with GCS at a dose of 50–100 mg per day for the treatment of skin processes in HF and hypocomplementary HF syndrome [11, 21, 22]. Side effects of dapsone include headache, non-hemolytic anemia and agranulocytosis, which requires evaluation of a complete blood count during treatment. In patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, the use of the drug can cause severe hemolysis. In such patients, enzyme levels should be measured before initiating dapsone therapy [23].

As an alternative to dapsone and when its use is contraindicated, colchicine is used at an initial dose of 0.5–0.6 mg per day orally. If there is no effect within several weeks, the dose of colchicine can be increased to 1.5–1.8 mg per day. After starting treatment, it is necessary to evaluate the results of a complete blood count due to the possible development of cytopenias associated with the use of the drug [23].

Severe urticarial vasculitis

In patients with severe HF and refractory, systemic and/or life-threatening symptoms, GCS are used in combination with other drugs (in order of preference): mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, azathioprine and cyclosporine. Cyclophosphamide is rarely prescribed due to potential toxicity and lack of effectiveness. Over the past few years, there has been increasing evidence supporting the use of biological agents: rituximab, anakinra and canakinumab [2, 24–26].

Mycophenolate mofetil has been effective in the treatment of hypocomplementary HF syndrome as maintenance therapy after disease control has been achieved with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide [24]. Recommended dosage: 0.5–1 g twice daily.

Methotrexate was useful as a steroid-sparing agent in one case [25] and caused exacerbation of HF in another [27].

Azathioprine was effectively used at a starting dose of 1 mg/kg per day in combination with prednisolone for HF with kidney and skin damage [28, 29]. If there is no effect within several weeks, the dose may be increased to the maximum recommended (2.5 mg/kg per day).

Cyclosporine A has been effective in hypocomplementary HF syndrome, especially in the renal and pulmonary complications of the syndrome [30], and also as a steroid-sparing agent [31]. The initial dose of the drug is 2–2.5 mg/kg per day. If there is no effect within several weeks, the dose can be increased to 5 mg/kg per day. The drug is nephrotoxic and may cause increased blood pressure.

Rituximab has been used in several patients with severe HF with varying efficacy [26, 32]. Anakinra was effective in patients with HF that was poorly responsive to other therapies [33]. Canakinumab was prescribed to 10 patients with HC, all of whom showed a marked improvement in the course of the disease, a decrease in the level of inflammatory markers and the absence of severe side effects [34].

Interferon A was effective both in monotherapy and in combination with ribavirin when CV was combined with hepatitis C or A [14, 35]. The effectiveness of other drugs, such as cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin and reserpine, has been poorly studied and is shown only in isolated clinical cases [36–38].

Conclusion

HF has a chronic and unpredictable course with an average duration of 3–4 years, and in some cases up to 25 years [39]. In one study, 40% of patients experienced complete remission of the disease within 1 year [15]. Mortality is low if there are no renal or pulmonary complications. When a group of patients was observed for 12 years, most of them did not experience the development of UV-related diseases (oncological, connective tissue, etc.). In isolated cases, the evolution of UD into systemic lupus erythematosus [12, 40] and Sjögren's syndrome [41] has been reported. When a disease that has become a possible cause of vasculitis is identified, the course and prognosis of vasculitis depend on the treatment of the underlying pathology. Fatal outcomes in patients with HF can include laryngeal edema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, respiratory failure, sepsis, renal failure and myocardial infarction [15].

There is a need for well-designed randomized placebo-controlled studies to better understand the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease, clarify the course and prognosis of different forms of HF, as well as study the effectiveness and safety of existing agents and search for new highly effective therapy.

Literature

- Zuberbier T., Aberer W., Asero R., Bindslev-Jensen C., Brzoza Z., Canonica GW, Church MK, Ensina LF, Gimenez-Arnau A., Godse K., Goncalo M., Grattan C., Hebert J., Hide M., Kaplan A., Kapp A., Abdul Latiff AH, Mathelier-Fusade P., Metz M., Nast A., Saini SS, Sanchez-Borges M., Schmid-Grendelmeier P., Simons FE , Staubach P., Sussman G., Toubi E., Vena GA, Wedi B., Zhu XJ, Maurer M. The EAACI/GA (2) LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update // Allergy. 2014. T. 69. No. 7. pp. 868–887.

- Kolkhir P.V., Olisova O.Yu., Kochergin N.G. Syndrome of hypocomplementary urticarial vasculitis at the onset of systemic lupus erythematosus // Bulletin of Dermatology and Venereology. 2013. No. 2. P. 53–61.

- Zuberbier T., Henz BM, Fiebiger E., Maurer D., Stingl G. Anti-FcepsilonRIalpha serum autoantibodies in different subtypes of urticaria // Allergy. 2000. T. 55. No. 10. P. 951–954.

- Natbony SF, Phillips ME, Elias JM, Godfrey HP, Kaplan AP Histologic studies of chronic idiopathic urticaria // J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983. T. 71. No. 2. P. 177–183.

- Monroe EW Urticarial vasculitis: an updated review // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981. T. 5. No. 1. P. 88–95.

- Warin RP Urticarial vasculitis // Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983. T. 286. No. 6382. P. 1919–1920.

- Saigal K., Valencia IC, Cohen J., Kerdel FA Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis with angioedema, a rare presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus: rapid response to rituximab // J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003. T. 49. No. 5 Suppl. pp. S283–285.

- Davis MD, Daoud MS, Kirby B., Gibson LE, Rogers RS, 3rd. Clinicopathologic correlation of hypocomplementemic and normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998. T. 38. No. 6. Pt 1. P. 899–905.

- Jachiet M., Flageul B., Deroux A., Le Quellec A., Maurier F., Cordoliani F., Godmer P., Abasq C., Astudillo L., Belenotti P., Bessis D., Bigot A., Doutre MS, Ebbo M., Guichard I., Hachulla E., Heron E., Jeudy G., Jourde-Chiche N., Jullien D., Lavigne C., Machet L., Macher MA, Martel C., Melboucy-Belkhir S., Morice C., Petit A., Simorre B., Zenone T., Bouillet L., Bagot M., Fremeaux-Bacchi V., Guillevin L., Mouthon L., Dupin N., Aractingi S., Terrier B. The clinical spectrum and therapeutic management of hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis: data from a French national study of fifty-seven patients // Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015. T. 67. No. 2. P. 527–534.

- Mehregan DR, Hall MJ, Gibson LE Urticarial vasculitis: a histopathologic and clinical review of 72 cases // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992. T. 26. No. 3. Pt 2. P. 441–448.

- Wisnieski JJ, Baer AN, Christensen J, Cupps TR, Flagg DN, Jones JV, Katzenstein PL, McFadden ER, McMillen JJ, Pick MA et al. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. Clinical and serologic findings in 18 patients // Medicine (Baltimore). 1995. T. 74. No. 1. P. 24–41.

- Bisaccia E., Adamo V., Rozan SW Urticarial vasculitis progressing to systemic lupus erythematosus // Arch Dermatol. 1988. T. 124. No. 7. P. 1088–1090.

- Callen JP, Kalbfleisch S. Urticarial vasculitis: a report of nine cases and review of the literature // Br J Dermatol. 1982. T. 107. No. 1. P. 87–93.

- Hamid S., Cruz PD, Jr., Lee WM Urticarial vasculitis caused by hepatitis C virus infection: response to interferon alfa therapy // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998. T. 39. No. 2. Pt 1. P. 278–280.

- Sanchez NP, Winkelmann RK, Schroeter AL, Dicken CH The clinical and histopathologic spectrum of urticarial vasculitis: study of forty cases // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982. T. 7. No. 5. P. 599–605.

- Davis MD, Brewer JD Urticarial vasculitis and hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome // Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004. T. 24. No. 2. P. 183–213.

- Wisnieski JJ Urticarial vasculitis // Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000. T. 12. No. 1. P. 24–31.

- Misiani R., Bellavita P., Fenili D., Borelli G., Marchesi D., Massazza M., Vendramin G., Comotti B., Tanzi E., Scudeller G. et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia // Ann Intern Med. 1992. T. 117. No. 7. P. 573–577.

- Pawlotsky JM, Roudot-Thoraval F., Simmonds P., Mellor J., Ben Yahia MB, Andre C., Voisin MC, Intrator L., Zafrani ES, Duval J., Dhumeaux D. Extrahepatic immunologic manifestations in chronic hepatitis C and hepatitis C virus serotypes // Ann Intern Med. 1995. T. 122. No. 3. P. 169–173.

- Ferri C., La Civita L., Cirafisi C., Siciliano G., Longombardo G., Bombardieri S., Rossi B. Peripheral neuropathy in mixed cryoglobulinemia: clinical and electrophysiologic investigations // J Rheumatol. 1992. T. 19. No. 6. P. 889–895.

- Eiser AR, Singh P., Shanies HM Sustained dapsone-induced remission of hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis - a case report // Angiology. 1997. T. 48. No. 11. P. 1019–1022.

- Muramatsu C., Tanabe E. Urticarial vasculitis: response to dapsone and colchicine // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985. T. 13. No. 6. P. 1055.

- Venzor J., Lee WL, Huston DP Urticarial vasculitis // Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2002. T. 23. No. 2. P. 201–216.

- Worm M., Sterry W., Kolde G. Mycophenolate mofetil is effective for maintenance therapy of hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis // Br J Dermatol. 2000. T. 143. No. 6. P. 1324.

- Stack PS Methotrexate for urticarial vasculitis // Ann Allergy. 1994. T. 72. No. 1. P. 36–38.

- Mukhtyar C., Misbah S., Wilkinson J., Wordsworth P. Refractory urticarial vasculitis responsive to anti-B-cell therapy // Br J Dermatol. 2009. T. 160. No. 2. P. 470–472.

- Borcea A., Greaves MW Methotrexate-induced exacerbation of urticarial vasculitis: an unusual adverse reaction // Br J Dermatol. 2000. T. 143. No. 1. P. 203–204.

- Moorthy AV, Pringle D. Urticaria, vasculitis, hypocomplementemia, and immune-complex glomerulonephritis // Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1982. T. 106. No. 2. P. 68–70.

- Ramirez G., Saba SR, Espinoza L. Hypocomplementemic vasculitis and renal involvement // Nephron. 1987. T. 45. No. 2. P. 147–150.

- Soma J., Sato H., Ito S., Saito T. Nephrotic syndrome associated with hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome: successful treatment with cyclosporin A // Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999. T. 14. No. 7. P. 1753–1757.

- Renard M., Wouters C., Proesmans W. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in a boy with hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis // Eur J Pediatr. 1998. T. 157. No. 3. P. 243–245.

- Mallipeddi R., Grattan CE Lack of response to severe steroid-dependent chronic urticaria to rituximab // Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007. T. 32. No. 3. P. 333–334.

- Botsios C., Sfriso P., Punzi L., Todesco S. Non-complementaemic urticarial vasculitis: successful treatment with the IL-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra // Scand J Rheumatol. 2007. T. 36. No. 3. P. 236–237.

- Krause K., Mahamed A., Weller K., Metz M., Zuberbier T., Maurer M. Efficacy and safety of canakinumab in urticarial vasculitis: an open-label study // J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013. T. 132. No. 3. P. 751–754, e755.

- Matteson EL Interferon alpha 2 a therapy for urticarial vasculitis with angioedema apparently following hepatitis A infection // J Rheumatol. 1996. T. 23. No. 2. P. 382–384.

- Worm M., Muche M., Schulze P., Sterry W., Kolde G. Hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis: successful treatment with cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone pulse therapy // Br J Dermatol. 1998. T. 139. No. 4. P. 704–707.

- Berkman SA, Lee ML, Gale RP Clinical uses of intravenous immunoglobulins // Ann Intern Med. 1990. T. 112. No. 4. P. 278–292.

- Demitsu T., Yoneda K., Iida E., Takada M., Azuma R., Umemoto N., Hiratsuka Y., Yamada T., Kakurai M. Urticarial vasculitis with haemorrhagic vesicles successfully treated with reserpine // J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008. T. 22. No. 8. pp. 1006–1008.

- Soter NA Chronic urticaria as a manifestation of necrotizing venulitis // N Engl J Med. 1977. T. 296. No. 25. P. 1440–1442.

- Soylu A., Kavukcu S., Uzuner N., Olgac N., Karaman O., Ozer E. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis in a 4-year-old girl // Pediatr Int. 2001. T. 43. No. 4. P. 420–422.

- Aboobaker J., Greaves MW Urticarial vasculitis // Clin Exp Dermatol. 1986. T. 11. No. 5. P. 436–444.

P. V. Kolhir1, Candidate of Medical Sciences O. Yu. Olisova, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

GBOU VPO First Moscow State Medical University named after. I. M. Sechenova Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

1 Contact information

Classification

According to the causes of occurrence, vasculitis is divided into 2 types:

- primary (independent disease);

- secondary (complication due to other diseases, medications, intoxications).

Depending on the size of the blood vessels where the pathology is observed, lesions are distinguished:

- small vessels (capillaries, arterioles, venules);

- middle vessels;

- large vessels (aorta, pulmonary artery);

- different types of vessels at the same time;

- a certain organ.

There are more than 25 types of vasculitis in the world, each of which differs in symptoms, treatments and prognosis.