Hypoplasia is a fundamental term in pathological anatomy, denoting underdevelopment of the tissues of a particular organ or the entire organism, which is determined by defects during embryonic maturation. Any organ can succumb to hypoplasia: arteries, heart, brain, kidneys, testicles or knee joint.

Intrauterine underdevelopment of an organ refers to disorders of adaptation and adaptation of the body. This disease is an irreversible process. Related concepts:

- Aplasia is an extreme degree of underdevelopment of an organ that appears in a newborn in its rudimentary form.

- Dysplasia is the abnormal formation of an organ.

The disease does not always manifest itself from the moment the child is born. Underdevelopment of an organ, if it is paired, can be compensated by another organ. For example, each kidney is 10% loaded. If one organ is hypoplastic, the other kidney will be 30-50% loaded. Often, a malformation is discovered by chance during a routine examination.

Causes

The following reasons give rise to it:

- Hereditary factors. For example, one of the parents may carry a recessive gene, which, due to consanguineous marriages, manifests itself in the child. Characteristic of closed communities where incest is permitted. A striking example is cerebellar hypoplasia due to disruption of the VLDLR gene, which manifests itself in cases of consanguineous blood mixing.

- Teratogenic factors: physical, biological and chemical effects on the body of the mother and child. For example, neuroinfections, living in areas with high levels of radiation, drugs that have not passed the teratogenicity test.

- Injuries during pregnancy.

- Maternal toxicosis.

- Smoking, alcoholism and drug addiction of parents.

- Pathologically reduced amount of amniotic fluid.

Symptoms

The specificity of the signs is determined by the localization of hypoplasia.

Hypoplasia of the cerebral artery

Underdevelopment of the arteries of the brain leads to a decrease in its blood flow due to a narrowing of the lumen or the absence of a vessel altogether. Due to the fact that the unit volume of blood circulation decreases, the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the brain decreases, which leads to the following symptoms:

- constant fatigue;

- headaches and dizziness;

- sudden changes in blood pressure;

- disturbance of the emotional state: irritability, excitability, intolerance to bright light or sound;

- deterioration of cognitive functions: decreased general intelligence, slow thinking, low short-term memory, impaired concentration;

- hypoplasia of cerebral vessels can provoke oligophrenia - congenital mental retardation of the child, since during intrauterine development the fetal brain did not receive the proper amount of blood and oxygen.

Hypoplasia of the posterior communicating arteries

Vascular underdevelopment leads to:

- dizziness and nausea;

- paresthesia: numbness, tingling, feeling of heat in the extremities;

- diplopia – double vision;

- deterioration of coordination.

Hypoplasia of the right vertebral artery

Impaired development of the artery leads to vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Clinical picture:

- sudden onset of dizziness that lasts from a few minutes to an hour; in severe cases, the patient begins to vomit, he sweats, his heart rate is disturbed and his blood pressure changes; sometimes dizziness leads to fainting;

- headache, usually localized in the back of the head; the pain is dull and throbbing;

- short-term vision loss; spots appear before the eyes, sometimes the lateral fields of vision disappear;

- diplopia;

- sudden and severe hearing loss; the appearance of tinnitus;

- psychasthenic syndrome: apathy, fatigue, loss of interest in the world, irritability and fatigue;

- if the disease progresses, speech and hearing impairments appear, and swallowing function becomes impaired;

- possible consequences are transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke.

Hypoplasia of the left transverse sinus

The clinical picture of the disease depends on the degree of underdevelopment. In mild forms of hypoplasia there is no symptom. If hypoplasia is already visualized on magnetic resonance imaging, it can manifest itself as an acute onset of the disease, night headaches, nausea and vomiting. Deep hypoplasia can cause sinus thrombosis, papilledema, and sudden loss of visual fields.

Hypoplasia of the right posterior communicating artery

This vessel is part of the Circle of Willis, a collection of arteries located at the base of the brain. It provides compensation for blood supply in the event that the main main vessels are unable to do so. An abnormality of the artery does not cause symptoms, but leads to an asymmetry of blood supply. The junction of Willis arteries acts as a lifeline when the main vessel does not supply blood to the brain. With hypoplasia there is no such life preserver.

Hypoplasia of the left brain

The pathology is characterized by variability of the condition, but has a common root of symptoms:

- severe headaches in the occipital region, most often of a pulsating nature;

- frequent dizziness;

- increased blood pressure; feeling of squeezing in the head;

- impairment of coordination and higher skills;

- drowsiness and lethargy;

- paresthesia;

- disturbance of perception: visual and auditory illusions (distortion of the perception of really existing objects and phenomena). For example, in carpet drawings the patient looks at a fantastic monster who is trying to kill him;

- emotional disorders: irritability, mood lability;

- sleep disturbance;

- neck pain

Difficulties in diagnosing thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses

Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses is more common in young women than in men, but is generally rare (up to 1% of all cases of cerebral infarction) [1]. According to ISCVT (International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis, 2004), the incidence annually is 3–4 cases per 1 million in adults and up to 7 cases per 1 million in children. The mortality rate for this disease ranges from 5 to 30%; during more than 2 years of observation, a corresponding figure of 8.3% was recorded. At the same time, more than 90% of patients had a favorable prognosis. The main risk factors for the development of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses in the population are infectious inflammatory processes (otitis, mastoiditis, sinusitis, septic conditions) and non-infectious causes. Non-infectious causes of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses can be localized or general. The most commonly cited are traumatic brain injury, tumors, head and neck surgery, and pacemaker implantation or central venous catheter placement. Common conditions that contribute to thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses include conditions such as hemodynamic compromise (eg, congestive heart failure, dehydration), blood disorders (polycythemia, sickle cell disease, thrombocytopenia), and coagulopathy (disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome). , deficiency of antithrombin, protein C and protein S), as well as thrombophilic conditions associated with pregnancy, childbirth and the use of oral contraceptives, antiphospholipid syndrome, systemic vasculitis. However, in 15% of cases the cause of sinus thrombosis remains unknown [5]. Difficulties in diagnosing thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses are due to the polymorphism of its clinical picture and the variability of the structure of the cerebral venous system. Anatomical features of the structure of

the cerebral venous system

In the development of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and sinuses, an important role is played by the anatomical features of the structure of the cerebral venous system (Fig. 1).

Unlike arteries and peripheral veins, cerebral veins lack a muscular wall and valve apparatus. The venous system of the brain is characterized by “branching”, a large number of anastomoses and the fact that one vein can receive blood from the basins of several arteries. Cerebral veins are divided into superficial and deep. Superficial veins - the superior cerebral vein, the superficial middle cerebral vein (Labbe vein), the inferior anastomatic vein (Trolar vein), the inferior cerebral veins - lie in the subarachnoid space and, anastomosing among themselves, form a network on the surfaces of the cerebral hemispheres. The main mass of venous blood from the cortex and white matter flows into the superficial veins, and then into the nearby sinus of the dura mater. Blood enters the deep cerebral veins from the veins of the choroid plexus of the lateral ventricles, basal ganglia, thalamus, midbrain, pons, medulla oblongata and cerebellum. The superficial and deep veins drain into the sinuses of the dura mater. The superficial veins drain mainly into the superior sagittal sinus. The main collectors of the deep veins are the great cerebral vein (vein of Galen) and the straight sinus. Blood from the superior sagittal and direct sinuses enters the transverse and sigmoid sinuses, which collect blood from the cranial cavity and drain it into the internal jugular vein. In the development of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses, 2 mechanisms are involved that determine the symptoms of the disease. The first is occlusion of the cerebral veins, causing cerebral edema and impaired venous circulation. The second link in the pathogenesis of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses is the development of intracranial hypertension due to occlusion of large venous sinuses. Normally, cerebrospinal fluid is transported from the cerebral ventricles through the subarachnoid space of the lower and superolateral surfaces of the cerebral hemispheres, adsorbed in the arachnoid plexuses and flows into the superior sagittal sinus. With thrombosis of the venous sinuses, venous pressure increases, as a result of which the absorption of cerebrospinal fluid is impaired and intracranial hypertension develops [5]. Both of these mechanisms determine the clinical symptoms of sinus thrombosis. Clinic and diagnosis

Clinical manifestations of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses depend on the location of thrombosis, the speed of its development and the nature of the underlying disease.

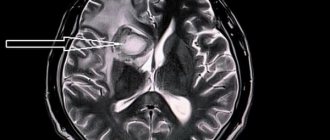

Severe disorders of the venous circulation are characterized by headache, vomiting, swelling of the optic discs, focal and generalized convulsions, and progressive depression of consciousness. However, with early recognition of the process, the clinical picture may be less pronounced. Focal neurological disorders can occur with isolated thrombosis of deep or superficial veins or with the spread of thrombosis from the sinuses to the veins. Meningeal syndrome is considered a rare manifestation of uncomplicated sinus thrombosis. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure, according to most authors, is normal or moderately elevated. The composition of the cerebrospinal fluid can be either unchanged or with a slightly increased protein content and pleocytosis of no more than 200/3 [1, 11–13]. Septic thrombosis of the transverse and sigmoid sinuses is characterized by a pronounced range of body temperature, leukocytosis, and accelerated ESR, but the use of antibiotics can smooth out these manifestations. Swelling of the mastoid area, pain on palpation, and less filling of the internal jugular vein on the affected side are very common. Sometimes thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus spreads to the internal jugular vein, which is accompanied by local inflammatory changes along the vein [1]. In contrast to arterial thrombosis and thromboembolism, neurological symptoms in thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses more often develop subacutely - within a period of several days to 1 month. (50–80% of cases), although an acute onset may also occur (20–30% of cases) [6]. The most common symptom of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses is intense headache (92% of patients), which is a reflection of the development of intracranial hypertension. It resembles the pain of subarachnoid hemorrhage and is not relieved by analgesics. In addition, according to ISCVT et al. [1, 7–13], the following symptoms are identified: – motor disorders – 42%; – convulsive syndrome – 37% (including status epilepticus – 13%); – psychomotor agitation – 25%; – aphasia – 18%; – visual impairment – 13%; – depression of consciousness (stunning, stupor, coma) – 13%; – disorders of the innervation of cranial nerves – 12%; – sensitivity disorders – 11%; – meningeal syndrome – 5%; – vestibulo-cerebellar disorders – 1%. In the long-term period, the most common symptoms are headache (14%) and convulsions (11%). The cavernous and superior sagittal sinuses are relatively rare sites of infection. More often, the intracranial process is the result of the spread of infection from the middle ear, paranasal sinuses, skin near the upper lip, nose and eyes. With thrombophlebitis of the marginal sinus, which usually occurs against the background of inflammation of the middle ear or mastoiditis, pain in the ear and pain when pressing on the mastoid process appear. After a few days or weeks, fever, headache, nausea and vomiting appear due to increased intracranial pressure. Swelling in the mastoid area, dilation of the veins and pain along the internal jugular vein in the neck occur. When the internal jugular vein is involved in the pathological process, pain in the neck and limitation of its movements are observed. Drowsiness and coma often develop. In 50% of patients, swelling of the optic discs is detected (in some patients it is unilateral). Seizures occur, but focal neurological symptoms are rare. The spread of the pathological process to the inferior petrosal sinus is accompanied by dysfunction of the abducens nerve and trigeminal nerve (Gradenigo syndrome). Thrombophlebitis of the cavernous sinus is secondary to oculonasal infections. The clinical syndrome is manifested by swelling of the orbit and signs of dysfunction of the oculomotor and trochlear nerves, the orbital branch of the trigeminal nerve and the abducens nerve. Subsequent spread of infection to the opposite cavernous sinus is accompanied by the occurrence of bilateral symptoms. The disease can begin acutely, with the appearance of fever, headache, nausea and vomiting. Patients complain of pain in the eyeball area, pain in the orbital area when pressed. Chemosis, edema and cyanosis of the upper half of the face are noted. Consciousness can remain clear. Ophthalmoplegia, sensory disturbances in the area of innervation of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, retinal hemorrhages and papilledema may occur. Infection of the superior sagittal sinus can occur when the infection is transferred from the marginal and cavernous sinuses or spreads from the nasal cavity, the focus of osteomyelitis, the epidural and subdural areas. The disease is manifested by fever, headache, swelling of the optic discs. Characteristic is the development of convulsive attacks and hemiplegia, first on one side and then on the other due to the spread of the pathological process to the cerebral veins. Movement disorders may manifest as monoplegia or predominant involvement of the lower extremities. All types of thrombophlebitis, especially those caused by infection of the ear and paranasal sinuses, can be complicated by other forms of intracranial purulent processes, including bacterial meningitis and brain abscess. Due to the absence of pathognomonic clinical symptoms of the disease, instrumental and laboratory research methods are of utmost importance in diagnosing thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses. In recent years, the improvement of neuroimaging technologies has opened up new opportunities for the diagnosis of sinus thrombosis (MRI, MR, CT venosinusography). For example, when performing MRI in standard modes, it is now possible to determine signs of venous thrombosis, expressed in increased signal intensity in the T1 and T2 modes, as well as T2-FLAIR from the altered sinus (Fig. 2). When performing MR venosinusography, a decrease in the signal from blood flow in the right transverse sinus is detected, as well as a compensatory increase in the signal from blood flow in the left transverse sinus (Fig. 3). If after an MRI or CT examination the diagnosis remains unclear, it is possible to perform contrast digital subtraction angiography, which can detect not only sinus thrombosis, but also the rare isolated thrombosis of the cerebral veins. Also, during this study, it is possible to identify dilated and tortuous veins, which is an indirect sign of thrombosis of the cerebral venous sinuses [14]. At the same time, a careful assessment of neuroimaging data is necessary to exclude errors in diagnosis, which may include, for example, hypoplasia or congenital absence of the sinus [6, 15]. Treatment

As already noted, the development of symptoms in thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses is based on occlusion of the cerebral veins and sinuses, changes in brain tissue and the development of intracranial hypertension. This combination is potentially dangerous and may be associated with a poor prognosis in patients with thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out complex therapy, including pathogenetic therapy (recanalization of sinuses) and symptomatic therapy (fighting intracranial hypertension, infection) [1, 4, 10]. The main goal of therapy for thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses is to restore their patency. Currently, the drugs of choice in this situation are anticoagulants, in particular low molecular weight heparins (LMWH). According to research, the use of direct anticoagulants in the acute period of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses improves the prognosis and reduces the risk of death and disability [16]. In addition, the ISCVT study obtained the following data for 80 patients with cerebral vein and venous sinus thrombosis treated with LMWH: 79% of them recovered, 8% remained mildly symptomatic, 5% had significant neurological impairment, 8% of patients died [1]. These data indicate the effectiveness and safety of the use of LMWH in the acute period of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses. In case of development of septic sinus thrombosis, antibacterial therapy should be carried out using high doses of broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as cephalosporins (ceftriaxone, 2 g/day IV), meropenem, ceftazidine (6 g/day IV), vancomycin ( 2 g/day i.v.). At the same time, there is no consensus on the feasibility and safety of anticoagulant therapy, although most authors adhere to the tactics of managing such patients with LMWH [18]. At the end of the acute period of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses, it is recommended to prescribe indirect oral anticoagulants (warfarin, acenocoumarol) at a dose at which the international normalized ratio (INR) is 2–3. Direct anticoagulants are administered to the patient until the INR reaches target values. In case of thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses during pregnancy, the administration of indirect anticoagulants should be avoided due to their teratogenic potential and the possibility of penetration through the placental barrier. In such cases, continued treatment with indirect anticoagulants is recommended [18].

Currently, there are no studies clearly regulating the duration of use of oral anticoagulants. According to the recommendations of EFNS (2006), indirect anticoagulants should be used for 3 months. for secondary thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses, which developed in the presence of a so-called transient risk factor, from 6 to 12 months. – in patients with idiopathic thrombosis and in the presence of “minor” thrombophilic conditions, such as deficiency of proteins C and S, heterozygous mutation of Leiden factor or mutations in the prothrombin gene (G20210A). Lifelong anticoagulant therapy is recommended for patients with recurrent venous sinus thrombosis, as well as for the diagnosis of congenital thrombophilic conditions (homozygous Leiden factor mutation, antithrombin deficiency) [17]. In addition to basic therapy, measures should be taken to prevent complications such as seizures and intracranial hypertension. These conditions require management according to general rules (prescription of anticonvulsants, elevated head of the bed, mechanical ventilation in hyperventilation mode with positive expiratory pressure, administration of osmotic diuretics). The effectiveness of glucocorticosteroids for cerebral edema resulting from thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses has not been proven [19]. In some cases, in severe forms of thrombosis complicated by dislocation of brain structures, the issue of performing decompression hemicraniotomy, which is a life-saving operation, may be considered [20, 21]. This article presents the case histories of 3 patients who were at different times in the 2nd neurological department of the National Center of Neurology with a diagnosis of cerebral sinus thrombosis. The goal is to demonstrate modern capabilities for diagnosing and treating venous circulatory disorders. Patient K., 31 years old,

was admitted to the National Center of Neurology with complaints of intense headache, nausea, and vomiting.

History of illness:

within 2 weeks.

received treatment for herniated intervertebral discs using large doses of glucocorticosteroids and diuretics. On February 8, 2010, an intense headache that was not relieved by taking analgesics, nausea, vomiting, and photophobia suddenly appeared. The condition was regarded as increased intracranial pressure, and therefore diuretics were prescribed on an outpatient basis. On February 16, 2010, a generalized tonic epileptic seizure suddenly developed. The ambulance team hospitalized the patient to the clinic with a diagnosis of “Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Brain contusion,” which was subsequently removed. After treatment (venotonics, glucocorticosteroids, nootropics), the headache regressed. However, on March 7, 2010, headache, nausea, and vomiting suddenly reappeared. On March 19, 2010, the patient was hospitalized at the NCN. On examination:

pronounced expansion of the saphenous veins on the face.

The neurological status shows mild stiffness of the neck muscles. There are no focal symptoms. Laboratory research methods.

Lupus anticoagulant – 1.10%, negative result.

Antibodies to cardiolipins IgG – 15.8 U/ml, the result is weakly positive (normal is up to 10 U/ml). Homocysteine – 16 µmol/l (normal – up to 15 µmol/l). Antigen to von Willebrand factor – 273% (normal – up to 117%). Blood coagulation factors – without deviation from normal values. A blood test for thrombophilic mutations is negative. An examination by an ophthalmologist

revealed signs of intracranial hypertension: hyperemia and swelling of the optic discs, dilation and congestion of the veins in the fundus.

Instrumental research methods:

when performing MRI in T2 mode, an increase in the intensity of the MR signal from the superior sagittal and left sigmoid sinuses was noted (Fig. 4). When performing MR venosinusography, there is no blood flow in both transverse, superior sagittal and left sigmoid sinuses. Noteworthy is the increase in blood flow through the superficial cerebral and facial veins (Fig. 5). Diagnosis: thrombosis of both transverse, left sigmoid and superior sagittal sinuses. Treatment was carried out: nadroparin 0.6 ml 2 times/day subcutaneously for 10 days with a transition to warfarin (INR level 2–3), venotonics (diosmin orally, aminophylline intravenously), carbamazepine (convulsive syndrome). 10 days after the start of therapy, an improvement in well-being was noted - the headache decreased. During MR venosinusography, positive dynamics were noted - blood flow was restored in both transverse sinuses. After 4 months after treatment, the appearance of blood flow through the superior sagittal sinus was noted (Fig. 5). Anticoagulants are continued.

Patient M., 36 years old.

She was admitted to the National Center of Neurology with complaints of intense headache and pulsating noise on the right.

Life history:

migraine attacks without aura have been recurring since adolescence.

She took estrogen-containing contraceptives for a long time. Medical history:

On August 11, 2009, an intense headache suddenly developed, different in nature from ordinary migraine pain, which was not relieved by analgesics.

Later, a pulsating noise in the right ear, a feeling of “heaviness” in the head, nausea, staggering when walking, and weakness appeared. On August 21, 2009, she was hospitalized at the National Center of Neurology. Upon examination:

no cerebral, meningeal or focal symptoms were detected.

Laboratory research.

Lupus anticoagulant – 1.15%, negative result.

Antibodies to cardiolipins IgG – 30 U/ml (normal – up to 10 U/ml). After 3 months upon repeated examination at the Rheumatology Center - 10 U/ml, within normal limits. Homocysteine – 11 µmol/l (normal – up to 15 µmol/l). Coagulogram – without features. Blood coagulation factors – without pathology. A blood test for thrombophilic mutations is negative. Instrumental research methods.

Standard CT and MRI revealed no pathology. Contrast CT angiography revealed the absence of a signal from blood flow along the right sigmoid sinus (Fig. 6). Thrombosis of the right sigmoid sinus was diagnosed.

Treatment carried out:

nadroparin 0.6 ml 2 times/day subcutaneously with a transition to warfarin to achieve INR figures of 2–3 (6 months), aminophylline, rutoside. Due to repeated migraine attacks and prolonged pain syndrome, propranolol and antidepressants from the selective serotonin reuptake inhibition group were prescribed. During treatment, the headache disappeared. After 6 months During a control study (MR venosinusography), restoration of blood flow through the right sigmoid sinus was noted (Fig. 7). Taking into account the absence of signs of coagulopathy and a verified cause of sinus thrombosis, anticoagulant therapy continued for 6 months.

Patient K., 56 years old,

received on August 13, 2010. She made no complaints due to decreased criticism of her condition.

Life history:

arterial hypertension, deep vein thrombosis of the legs.

History of the disease:

On August 13, 2010, the color perception of surrounding objects suddenly became impaired (the color of the house changed).

Relatives noticed inappropriate behavior - the patient began to “talk.” Weakness developed in the left arm and leg, walking was impaired, and convulsive twitching appeared in the left arm and leg. The ambulance team transported her to the National Center. On examination:

partially disoriented in place and time.

Adynamic. Sleepy. Reduced criticism of one's condition. Speech is not impaired. Meningeal symptoms are negative. There are no oculomotor disorders. The face is symmetrical, the tongue is in the midline. There are no bulbar disorders. Mild left-sided hemiparesis with increased muscle tone of the plastic type. Tendon and periosteal reflexes are alive, S>D. Babinski reflex on the left. In the left limbs there are periodic clonic convulsive twitches of varying amplitude, lasting up to 1 minute. There are no sensory disorders. Laboratory tests:

homocysteine – 39 µmol/l (normal – up to 15 µmol/l), von Willebrand factor antigen – 231% (normal – up to 117%).

Lupus anticoagulant – 1.1%, negative result. Antibodies to cardiolipins IgG – 24 U/ml, the result is weakly positive (normal is up to 10 U/ml). Blood coagulation factors – without pathology. An examination by an ophthalmologist revealed signs of obstructed venous outflow. Instrumental studies:

MRI of the brain revealed an infarction with a hemorrhagic component, complicated by subarachnoid hemorrhage in the right hemisphere of the brain, as well as thrombosis of the right transverse sinus (Fig. 8).

Diagnosis

: infarction with a hemorrhagic component in the right hemisphere of the brain due to thrombosis of the right transverse and sigmoid sinuses, complicated by subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Treatment carried out:

enoxaparin 0.4 ml 2 times/day subcutaneously with switching to warfarin (continuous use) under the control of INR 2–3; venotonics (rutoside, aminophylline). Due to the detected hyperhomocysteinemia, folic acid and vitamin B12 were also prescribed. In addition, antihypertensive therapy was carried out. After 10 days from the start of therapy, the disappearance of clonic twitching in the left arm and leg, an increase in strength and range of motion were noted, the patient became more adequate, oriented in place and time. Upon repeated examination, the appearance of a signal from the blood flow along the right transverse sinus was noted (Fig. 9). Taking into account thrombosis of the right transverse sinus, a history of deep vein thrombosis of the legs, and an increase in homocysteine levels, the patient was recommended for continuous therapy with anticoagulants and folic acid.

Conclusion

In the 3 demonstrated cases, among the possible causes, the increased thrombogenic potential of the blood (increased level of antigen to von Willebrand factor, hormonal therapy, hyperhomocysteinemia) should apparently be put in first place. The thrombophilic state could serve as a trigger for the development of venous sinus thrombosis. Thus, in this situation, the main direction of pathogenetic therapy is the prescription of direct anticoagulants with a transition to indirect anticoagulants and maintaining INR values at 2–3. In addition, the importance of a thorough history taking has been demonstrated, in particular, close attention to the presence of an infectious process, traumatic brain injury, venous thrombosis, and taking medications that can provoke the development of a hypercoagulable state. The importance of a physical examination is also emphasized, which may reveal indirect signs of impaired venous outflow through the cerebral veins and venous sinuses (dilation of the facial veins in the first patient). In 2 patients, examination of the fundus revealed signs of impaired venous outflow and intracranial hypertension: congestive, swollen, hyperemic optic discs, dilated, congested veins in the fundus, absence of spontaneous venous pulse. All these signs, along with an indication of a new-onset, intense, difficult-to-treat headache, should give the clinician a reason to exclude disorders of cerebral venous circulation, which in turn is the key to successful treatment of patients and secondary prevention of this type of pathology.