There are several types of sugar comas, namely:

- Hyperglycemic – blood sugar levels are significantly higher than acceptable levels. More common in type 2 diabetics.

- Hypoglycemic – associated with a sharp drop or low blood sugar level. It can occur in patients with any type of diabetes.

- Ketoacidotic - due to an insufficient amount of insulin, ketone bodies (acetone) begin to be produced in the liver; if they are not removed in a timely manner, they accumulate, which becomes the cause of the development of coma. It is more common in patients diagnosed with type 1 diabetes.

- Hyperosmolar - manifests itself against the background of a sharp increase in sugar levels (up to 38.9 mmol/l) due to a violation of metabolic processes in the body. Most common in people over 50 years of age.

- Hyperlactic acidemia - due to disturbances in metabolic processes, lactic acid accumulates in large quantities in the blood and tissues, which causes the development of coma. Most common in older people.

The reason for the development of these conditions is late diagnosis, incorrect treatment or lack thereof. They do not develop immediately, but occur in several stages. If you notice alarming symptoms in time, the process will be reversible. Unfortunately, inattention and negligent attitude towards one’s own or someone else’s health causes death, and with this diagnosis this happens often. Therefore, both the patient and his relatives should know the symptoms of the development of each of these comas.

Acute complications of diabetes mellitus in the practice of an emergency physician

Acute complications of diabetes mellitus are life-threatening conditions caused by significant changes in blood sugar levels and associated metabolic disorders.

Acute complications of diabetes mellitus:

- hyperglycemic comas - ketoacidotic, hyperosmolar;

- hypoglycemic coma.

Diabetic ketoacidosis and non-ketonic hyperosmolar coma are characterized by varying degrees of insulin deficiency, excess production of counter-insulin hormones and dehydration. In some cases, signs of diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar coma may develop simultaneously.

Hypoglycemia is caused by an imbalance between the medicine used to treat diabetes (insulin or blood glucose-lowering tablets) and food intake or exercise.

The speed and timeliness of providing care to comatose patients largely determine the prognosis. Therefore, proper management of patients at the prehospital stage is very important.

In the structure of comas at the prehospital stage, hypoglycemic coma ranks third (5.4%), and diabetic coma (3%) ranks fifth (data from the NNPOSMP).

Diabetic ketoacidotic coma (DKA)

DKA is a very serious complication of diabetes mellitus, characterized by metabolic acidosis (pH less than 7.35 or bicarbonate concentration less than 15 mmol/L), increased anion gap, hyperglycemia above 14 mmol/L, and ketonemia. More often develops in type 1 diabetes. DKA accounts for 5 to 20 cases per 1000 patients per year (2/100). The mortality rate is 5-15%, for patients over 60 years old - 20%. More than 16% of patients with type 1 diabetes die from ketoacidotic coma. The cause of the development of DKA is an absolute or pronounced relative deficiency of insulin due to inadequate insulin therapy or an increased need for insulin.

Provoking factors: insufficient dose of insulin or skipping an insulin injection (or taking tableted glucose-lowering drugs), unauthorized cancellation of glucose-lowering therapy, violation of insulin administration technique, addition of other diseases (infections, trauma, surgery, pregnancy, myocardial infarction, stroke, stress, etc.) , dietary disorders (too many carbohydrates), physical activity with high glycemia, alcohol abuse, insufficient self-monitoring of metabolism, taking certain medications (corticosteroids, calcitonin, saluretics, acetazolamide, β-blockers, diltiazem, isoniazid, diphenin, etc. ).

Often the etiology of DKA remains unknown. It should be remembered that in approximately 25% of cases, DKA occurs in patients with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus.

There are three stages of diabetic ketoacidosis: moderate ketoacidosis, precoma, or decompensated ketoacidosis, coma.

Complications of ketoacidotic coma include deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, arterial thrombosis (myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, necrosis), aspiration pneumonia, cerebral edema, pulmonary edema, infections, rarely - gastrointestinal tract and ischemic colitis, erosive gastritis, late hypoglycemia. Severe respiratory failure, oliguria and renal failure are noted. Complications of therapy include cerebral and pulmonary edema, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia.

Diagnostic criteria for DKA

- The peculiarity of DKA is its gradual development, usually over several days.

- The presence of symptoms of ketoacidosis (the smell of acetone in the exhaled air, Kussmaul breathing, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain).

- The presence of symptoms of dehydration (decreased tissue turgor, tone of the eyeballs, muscle tone, tendon reflexes, body temperature and blood pressure).

When diagnosing DKA at the prehospital stage, it is necessary to find out whether the patient suffers from diabetes mellitus, whether there is a history of DKA, whether the patient is receiving glucose-lowering therapy, and if so, what kind, when was the last drug taken, the time of the last meal, whether excessive physical activity or alcohol intake, what recent diseases preceded the coma, whether there was polyuria, polydipsia and weakness.

Prehospital treatment of DKA (see Table 1) requires special attention to avoid errors.

Possible errors in therapy and diagnosis at the prehospital stage

- Prehospital insulin therapy without glycemic control.

- The emphasis in treatment is on intensive insulin therapy in the absence of effective rehydration.

- Insufficient volume of fluids administered.

- Administration of hypotonic solutions, especially at the beginning of treatment.

- Use of forced diuresis instead of rehydration. The use of diuretics simultaneously with the administration of fluids will only slow down the restoration of water balance, and in hyperosmolar coma, the use of diuretics is strictly contraindicated.

- Initiating therapy with sodium bicarbonate may be fatal. It has been proven that adequate insulin therapy in most cases helps eliminate acidosis. Correction of acidosis with sodium bicarbonate carries an exceptionally high risk of complications. The introduction of alkalis increases hypokalemia and disrupts the dissociation of oxyhemoglobin; carbon dioxide formed when sodium bicarbonate is administered increases intracellular acidosis (although the blood pH may increase); paradoxical acidosis is also observed in the cerebrospinal fluid, which can contribute to cerebral edema; the development of “rebound” alkalosis cannot be ruled out. Rapid administration of sodium bicarbonate (boost) can cause death due to the rapid development of hypokalemia.

- Administration of sodium bicarbonate solution without additional administration of potassium preparations.

- Withholding or not prescribing insulin for DKA in a patient who is unable to eat.

- Intravenous bolus injection of insulin. Only during the first 15-20 minutes is its concentration in the blood maintained at a sufficient level, so this route of administration is ineffective.

- Three to four times of subcutaneous short-acting insulin (RAI). ICD is effective for 4-5 hours, especially in conditions of ketoacidosis, so it should be prescribed at least five to six times a day without an overnight break.

- The use of sympathotonic drugs to combat collapse, which, firstly, are counter-insulin hormones, and, secondly, in diabetic patients their stimulating effect on glucagon secretion is much more pronounced than in healthy individuals.

- Incorrect diagnosis of DKA. With DKA, the so-called “diabetic pseudoperitonitis” often occurs, which simulates the symptoms of an “acute abdomen” - tension and pain in the abdominal wall, a decrease or disappearance of peristaltic noises, and sometimes an increase in serum amylase. Simultaneous detection of leukocytosis can lead to an error in diagnosis, as a result of which the patient ends up in the infectious (“intestinal infection”) or surgical (“acute abdomen”) department. In all cases of “acute abdomen” or dyspeptic symptoms in a patient with diabetes, it is necessary to determine glycemia and ketotonuria.

- Failure to measure glycemia in any patient who is unconscious, which often leads to erroneous diagnoses - “cerebrovascular accident”, “coma of unknown etiology”, while the patient has acute diabetic metabolic decompensation.

Hyperosmolar nonketoacidotic coma

Hyperosmolar non-ketoacidotic coma is characterized by severe dehydration, significant hyperglycemia (often above 33 mmol/l), hyperosmolarity (more than 340 mOsm/l), hypernatremia above 150 mmol/l, absence of ketoacidosis (maximum ketonuria (+)). It develops more often in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. It is 10 times less common than DKA. Characterized by a higher mortality rate (15-60%). The reasons for the development of hyperosmolar coma are a relative deficiency of insulin and factors that provoke the occurrence of dehydration.

Provoking factors: insufficient dose of insulin or skipping an insulin injection (or taking tableted glucose-lowering drugs), unauthorized cancellation of glucose-lowering therapy, violation of insulin administration technique, addition of other diseases (infections, acute pancreatitis, trauma, surgery, pregnancy, myocardial infarction, stroke, stress and etc.), dietary disorders (too many carbohydrates), taking certain medications (diuretics, corticosteroids, beta blockers, etc.), cooling, inability to quench thirst, burns, vomiting or diarrhea, hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

It should be remembered that a third of patients with hyperosmolar coma do not have a previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus.

Clinical picture

Severe thirst, polyuria, severe dehydration, arterial hypotension, tachycardia, focal or generalized convulsions increasing over several days or weeks. If, with DKA, disorders of the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system occur according to the type of gradual loss of consciousness and inhibition of tendon reflexes, then hyperosmolar coma is accompanied by a variety of mental and neurological disorders. In addition to the soporous state, which is also often observed in hyperosmolar coma, mental disorders often occur as delirium, acute hallucinatory psychosis, and catotonic syndrome. Neurological disorders are manifested by focal neurological symptoms (aphasia, hemiparesis, tetraparesis, polymorphic sensory disorders, pathological tendon reflexes, etc.).

Diagnostic criteria

- Hyperosmolar non-ketoacidotic coma develops more slowly (within 5-14 days) than DKA. Dehydration is more pronounced (decreased tissue turgor, tone of the eyeballs, muscle tone, tendon reflexes, body temperature and blood pressure) with neurological symptoms, there is no ketoacidosis, ketonuria, anuria and azotemia occur more often in elderly and senile age.

Among possible errors in therapy (see Table 2) and diagnosis, it is customary to highlight the administration of hypotonic solutions at the prehospital stage, long-term administration of hypotonic solutions.

Hypoglycemic coma

Hypoglycemic coma develops due to a sharp decrease in blood glucose levels (below 3-3.5 mmol/l) and severe energy deficiency in the brain.

Provoking factors: overdose of insulin and TCC, skipping or inadequate meals, increased physical activity, excessive alcohol intake, taking medications (β-blockers, salicylates, sulfonamides, etc.).

Clinical picture

Symptoms of hypoglycemia are divided into early (cold sweat, especially on the forehead, pale skin, severe paroxysmal hunger, trembling hands, irritability, weakness, headache, dizziness, numbness of lips), intermediate (inappropriate behavior, aggressiveness, palpitations, poor coordination of movements, double vision, confusion) and late (loss of consciousness, convulsions).

Diagnostic criteria

- Sudden onset of symptoms, usually over a period of several minutes, less often hours.

- The presence of characteristic symptoms of hypoglycemia.

- Glycemia is below 3-3.5 mmol/l.

At the prehospital stage, it is necessary to find out: how long the patient has been suffering from diabetes mellitus, whether the patient receives hypoglycemic therapy, and if so, what kind, when was the last drug taken, whether there have been any dietary violations, whether there have been any episodes of hypoglycemia in the past, whether excessive physical activity and alcohol intoxication were allowed.

Therapy for hypoglycemic coma at the prehospital stage (see Table 3) includes the use of thiamine, prednisolone, glucose, adrenaline solution, magnesium sulfate.

After removing the patient from a hypoglycemic coma, it is recommended to use drugs that improve microcirculation and metabolism in brain cells (glutamic acid, aminolon, stugeron, cavinton) for three to six weeks.

Repeated hypoglycemia can lead to brain damage.

Possible diagnostic and therapeutic errors

- An attempt to introduce carbohydrate-containing products (sugar, etc.) into the oral cavity of an unconscious patient. This often leads to aspiration and asphyxia.

- Use of unsuitable foods (bread, chocolate, etc.) to relieve hypoglycemia. These foods do not have a sufficient sugar-raising effect or raise blood sugar levels too slowly.

- Incorrect diagnosis of hypoglycemia. Some symptoms of hypoglycemia may be mistakenly regarded as an epileptic seizure, stroke, “vegetative crisis,” etc. In a patient receiving hypoglycemic therapy, if there is a reasonable suspicion of hypoglycemia, its relief should begin immediately, even before receiving a response from the laboratory.

- Once a patient has been brought out of severe hypoglycemia, the risk of relapse is often not taken into account.

In patients in a comatose state of unknown origin, it is always necessary to assume the presence of glycemia. If it is reliably known that the patient has diabetes mellitus and at the same time it is difficult to differentiate the hypo- or hyperglycemic genesis of the coma, intravenous jet administration of glucose is recommended in a dose of 20–40–60 ml of 40% solution for the purpose of differential diagnosis and emergency assistance for hypoglycemic coma In the case of hypoglycemia, this significantly reduces the severity of symptoms and thus allows differentiation between the two conditions. In hyperglycemic coma, such an amount of glucose will have virtually no effect on the patient’s condition.

In all cases where it is not possible to measure blood glucose immediately, highly concentrated glucose should be administered empirically. If hypoglycemia is not treated urgently, it can be fatal.

The basic drugs for patients in a coma, in the absence of the possibility of clarifying the diagnosis and immediate hospitalization, are considered to be thiamine 100 mg IV, glucose 40% 60 ml and naloxone 0.4-2 mg IV. The effectiveness and safety of this combination have been repeatedly confirmed in practice.

Kh. M. Torshkhoeva, Candidate of Medical Sciences A. L. Vertkin, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor V. V. Gorodetsky, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of NNPO Emergency Medical Care, MGMSU

Symptoms

Coma does not occur instantly, usually everything happens gradually and there is time to change everything. On average, 1 to 3 days pass before the patient loses consciousness and falls into a “deep sleep.” The accumulation of ketone bodies and lactose is also not a quick process. For most diabetic comas, the symptoms will be similar, except for the hypoglycemic state.

The first signs of an approaching coma are an increased need for fluid (the person is constantly thirsty) and frequent urination. General weakness, deterioration of health, and headaches are detected. Nervous excitement gives way to drowsiness, nausea appears, and there is no appetite. This is the initial stage of development of this condition.

After 12-24 hours, without receiving adequate treatment, the condition will begin to worsen. There will be indifference to everything that is happening around, there will be a temporary loss of reason. The last stage will be the lack of reaction to external stimuli and complete loss of consciousness.

Against this background, changes occur in the body, which not only a doctor can notice. These include: decreased blood pressure and weak pulse, the skin feels warm to the touch, and the eyes are “soft.” In hypoglycemic or ketoacidotic coma, the patient's mouth will smell of acetone or fermented apples.

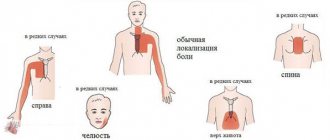

With lactic acidosis, cardiovascular failure will manifest itself, pain appears behind the sternum and in the muscles, abdominal pain and vomiting may appear. Hyperosmolar coma develops more slowly than others (5-14 days), at the last stage of development, breathing becomes intermittent, with shortness of breath, but there is no smell from the mouth, the skin and mucous membranes become dry, facial features become sharper.

Hypoglycemic coma develops rapidly, and action must be taken immediately after diagnosis. At the initial stage, a sharp feeling of hunger appears. In a matter of minutes, a person develops general weakness, a feeling of fear and inexplicable anxiety appears. Tremors appear throughout the body and increased sweating.

If during this period the patient does not raise the glucose level, a small piece of sugar or candy is enough, then complete loss of consciousness will follow and, in some cases, convulsions may appear. External signs: the skin is moist to the touch, the eyes remain firm, muscle tone is increased, but after a while the skin will dry out and become dry, which can make the diagnosis difficult.

These are the main signs of the onset of a coma, but it is not always possible to accurately diagnose yourself, so do not rush to feed the patient sugar or inject insulin, the consequences may be irreversible.

Clinical manifestations of hypoglycemia

Precursors are weakness, anxiety, trembling of arms and legs, sweating, and the appearance of hunger. Advanced stage: psychomotor agitation, then stupor, stupor or coma develops. The face is mask-like, severe sweating, tissue turgor is normal, muscle tone is high; tachycardia, blood pressure is initially increased, then it decreases. Clonic-tonic convulsions often occur. Sometimes hypoglycemic coma develops suddenly and is characterized by a triad of symptoms: loss of consciousness, muscle hypertonicity, and convulsions. With prolonged hypoglycemia, a clinical picture of cerebral edema develops. In a patient with diabetes mellitus, hypoglycemic coma is differentiated from hyperglycemic ketoacidotic coma.

Emergency measures for manifestations of hypoglycemia:

- if consciousness is preserved, take carbohydrate-containing products (sweet tea, apple or orange juice); in the absence of positive dynamics after 10-15 minutes. – repeated intake of easily digestible carbohydrates;

- calling an ambulance;

- in case of impaired consciousness - slowly inject 40% glucose solution intravenously - 1-2 ml / kg until the patient comes out of coma and the convulsions stop;

- when regaining consciousness, administer easily digestible carbohydrates orally;

- if there is no effect after 10-15 minutes. – repeated intravenous administration of 40% glucose solution up to 5 ml/kg;

- in the absence of positive dynamics, administer intravenous hydrocortisone 0.5-10 mg/kg body weight (prednisolone, dexamethasone are not administered due to the high risk of developing cerebral edema);

If the child’s consciousness has not recovered, enter:

- intravenous, intramuscular glucagon in a dose of 0.5 ml for children weighing up to 20 kg and 1.0 ml;

- with a weight of more than 20 kg or 0.18% solution of epinephrine (adrenaline) 0.1 ml/kg s.c.

If the patient does not regain consciousness, suspect cerebral edema! For cerebral edema, administer:

- 1% solution of furosemide (Lasix) 0.1-0.2 ml/kg intravenously or intramuscularly;

- 10% mannitol solution 0.5–1.0 g/kg intravenous drip in 10% glucose solution,

- dexamethasone solution 0.5-1 mg/kg (1 ml - 4 mg) intravenously,

- oxygen therapy.

Attention! If acute intracranial hypertension is suspected, limit intravenous infusion, but do not stop - catheter thrombosis is possible

Hospitalization in the intensive care unit (in the absence of consciousness), if the patient is conscious - in the endocrinology department of the hospital.

Diagnostics and first aid

When the first symptoms of one of the comatose states appear, you should immediately call an ambulance. A good place to start is to measure your blood sugar levels. For conditions caused by increased glucose levels, this figure will be higher than 33 mmol/l. With hypoglycemia, the sugar value will be below 1.5 mmol/l; the hyperosmolar state is characterized by an increase in blood plasma osmolarity - more than 350 mOsm/l.

If you lose consciousness, you should put the patient in a comfortable position and make sure that the head is not thrown back, nothing is obstructing breathing, and the tongue does not sink. If the need arises, an air duct must be introduced. After this, blood pressure is measured and the condition is corrected. If blood pressure is low, it needs to be raised, heart failure or another similar condition needs to be normalized.

To make a diagnosis, you will need not only a blood test, but also a urine test. So, with a sharp increase in blood sugar, it is also found in the urine, also affecting ketone bodies and lactic acid. If glucose levels are low, a urine test will be useless.

Treatment should be approached with caution, but there is a universal method. It is necessary to administer 10-20 cubes of 40% glucose intravenously to the patient. If the sugar level is high, this will not cause any special changes in the patient’s condition, but if the glucose level is low, it will save life.