Why is blood thinned?

Bleeding disorders can occur at any age. First of all, this problem concerns everyone over 50 years of age. Thick blood puts additional stress on the heart. This is due to the fact that it is more difficult to pump thick liquid through a huge circulatory system; more power is required, which the heart must produce. At the same time, the pulse becomes faster and the tremors become stronger. During such work, the heart muscle wears out faster, the valves fail, and the tightness of the atria is compromised.

Another danger of thick blood is the formation of blood clots. Thrombi are individual clots that form as a result of platelets sticking to each other. The resulting blood clots attach to the walls of blood vessels and interfere with blood flow. But the worst thing for a person’s life is a detached blood clot. As it rushes through the circulatory system, the current carries it to the lungs and then to the heart. By blocking the lumen of an artery in one of the organs, a blood clot causes an ischemic stroke, which often leads to death.

In addition, thick blood cannot supply organs and tissues with nutrients in a timely manner, which is why the body suffers from mild forms of hypoxia. The thicker the biological fluid, the more difficult it is for it to rise from the lower extremities to the heart. As a result, blood stagnation in the veins, thrombosis and varicose veins appears.

ASPIRIN. Stable positions and new opportunities after the 100th anniversary

Antiplatelet drugs, in the absence of contraindications, are an essential component in the treatment and prevention of atherothrombosis. The International Committee for the Analysis of Trials of Antithrombotic Drugs regularly (as large studies are completed) organizes meta-analyses, the results of which have confirmed the effectiveness of aspirin in the treatment of patients with myocardial infarction (MI), acute coronary syndrome (ACS) without ST-segment elevation on the ECG in relation to reducing the risk of developing death and MI. In addition, the effectiveness of long-term use of aspirin in patients who have suffered ACS has been proven in relation to total death, MI and stroke. All this gave reason to include aspirin in the list of mandatory medications for the above pathology and was reflected in practical recommendations for doctors.

Despite the abundance of studies on antiplatelet drugs, until recently there was no clear answer to a number of questions: in particular, about the advisability of using antiplatelet drugs in patients with acute ischemic stroke, in the presence of a permanent form of atrial fibrillation, stable angina, and atherosclerotic lesions of the arteries of the lower extremities. In addition, the issue of the minimum effective dose of aspirin and the advisability of combinations of several antiplatelet agents and antiplatelet agents with anticoagulants has not yet been clarified. These, as well as other problems less covered in the domestic literature, will be the subject of this review.

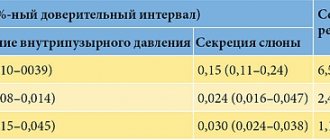

In 2002, the results of another large meta-analysis were published [1] assessing the effectiveness of antiplatelet drugs, which included 287 studies (195 controlled in more than 135 thousand high-risk patients). The effectiveness of treatment with various antiplatelet agents was compared in 77 thousand patients. The results of the meta-analysis found that the use of antiplatelet drugs reduces the total risk of vascular events by 22%, non-fatal myocardial infarction by 34%, non-fatal stroke by 25%, and vascular death by 15%.

Aspirin remains the most widely used antiplatelet drug today, the clinical efficacy and safety of which has been confirmed by numerous controlled studies and meta-analyses. The mechanism of action of aspirin is associated with irreversible inhibition of platelet cyclooxygenase-1, which results in a decrease in the formation of thromboxane A2, one of the main inducers of aggregation, as well as a powerful vasoconstrictor released from platelets upon their activation. A pooled analysis of the results of 65 studies, which included 59,395 patients at high risk of developing vascular complications, showed that taking aspirin reduced the total risk of MI, stroke, and vascular death by 23% [1]. Prescription of low doses of aspirin (75-150 mg/day) for long-term therapy was no less effective than medium (160-325 mg/day) or high (500-1500 mg/day). In clinical situations, such as unstable angina, myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, the initial dose should be at least 150 mg/day [1]. To date, few studies have been conducted using very low doses of aspirin (less than 75 mg/day), so the question of the effectiveness of a dose of the drug <75 mg/day remains open.

Aspirin in the treatment and prevention of ischemic stroke

Aspirin in doses from 30 to 1500 mg/day has been used for a long time and has been successfully used in the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. Direct comparative studies have provided evidence of the equal effectiveness of low, medium and high doses of aspirin in patients with stroke or transient cerebrovascular accident (TCI) [2-4].

In a pooled analysis of the results of 21 studies on the secondary prevention of stroke or stroke, conducted in more than 18 thousand patients, the reduction in the risk of recurrent vascular events with antiplatelet therapy was 22% [1]. This avoided the development of 36 vascular complications, including 25 recurrent strokes and six myocardial infarctions, as well as seven cases of vascular and 15 total deaths per 1000 patients over two years. All these undoubted benefits were accompanied by an increase in the risk of major bleeding to 1-2 per 1000 patients per year. A dose of aspirin of 75 mg/day is considered minimally effective for the prevention of ischemic stroke (as for most cardiovascular diseases).

Until recently, the effectiveness and safety of aspirin administration in the acute phase of ischemic stroke have been little studied. Two large studies, CAST and IST, which included more than 40 thousand patients, confirmed the feasibility of using aspirin in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke [5, 6]. The drug was prescribed within 48 hours from the onset of symptoms of the disease, the dose was 160 and 300 mg/day, respectively, and the duration of treatment was two to four weeks. A pooled analysis of the CAST and IST trials found that immediate aspirin avoided nine deaths and recurrent nonfatal strokes in the first month and 13 deaths and permanent disability in the next six months per 1000 patients treated. The risk of developing hemorrhagic stroke was 2 per 1000 patients, and major bleeding - 3 per 1000.

Aspirin for atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the main cause of embolic complications, primarily stroke, accounting for approximately 50% of cases [7]. The risk of developing ischemic stroke in patients with MA increases with age, as well as in the presence of concomitant cardiovascular diseases. Indirect anticoagulants are the absolute drugs of choice for MA. However, aspirin also turned out to be effective in patients with MA. According to five randomized trials, the reduction in the risk of vascular events with aspirin therapy was 24% [8]. Aspirin was found to be more effective in primary prevention of stroke in patients with MA than in secondary prevention [9].

Currently, aspirin is recommended for the primary prevention of stroke in patients with MA younger than 65 years of age, in the absence of cardiovascular diseases [10]. Also, the prescription of aspirin is possible for patients with an average risk of stroke (2-5% per year), if there is no more than one of the following factors: age 65-75 years, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, thyrotoxicosis. In the presence of more than one of the above average risk factors, as well as left ventricular dysfunction, arterial hypertension, a history of stroke or embolism, mitral heart disease, or aged 75 years or older, the prescription of indirect anticoagulants is indicated [10]. The recommended dose of aspirin in patients with MA is 325 mg/day.

Aspirin for stable angina pectoris

Considering the rather low risk of developing vascular events in stable angina without a history of myocardial infarction (4-8% per year), for a long time it was not possible to obtain convincing evidence of the preventive effect of aspirin in these patients.

The clearest evidence of the effectiveness of aspirin in preventing MI and vascular death in patients with stable angina was obtained in the double-blind, placebo-controlled SAPAT study [11], which was conducted in 2035 patients receiving the β-blocker sotalol at an average dose of 160 mg. Aspirin was prescribed at a dose of 75 mg/day, the observation period was 50 months. When treated with aspirin, compared with placebo, the risk of MI and sudden death decreased by 34%, and vascular death, stroke and overall mortality - by 22-32%.

Aspirin for atherosclerotic lesions of the arteries of the lower extremities

Patients with atherosclerotic lesions of the arteries of the lower extremities (ALAD) represent a group at high risk of developing thrombotic complications. The results of prospective studies have shown that mortality in patients with APANC is two to four times higher than in an age- and sex-matched population [12, 13]. Combined damage to the coronary, brachiocephalic and lower extremity arteries, according to various studies, is observed in 20-50% of cases [14]. Atherosclerotic lesions of the coronary arteries of the heart, according to the results of coronary angiography, were noted in 90% of patients with APANK, while hemodynamically significant stenosis was observed in almost 60% [15]. Among the causes of death in patients with APANK, the first place is taken by ischemic heart disease (IHD) - 55%, followed by stroke - 10%, damage to vascular areas of other localization - 10%, other causes - 25% [12].

In a pooled analysis of the results of 42 studies, including 9214 patients with APANK (including those who had undergone angioplasty or bypass surgery of the arteries of the lower extremities), the administration of antiplatelet drugs reduced the total risk of developing vascular events by 23%, p-0.004 [1].

In the CAPRIE study [16], which compared the effectiveness of long-term use of clopidogrel and aspirin in various high-risk patients, the greatest reduction in the number of vascular events among those receiving clopidogrel was achieved in patients with APANK (23.8% vs 8.7% all patients). The higher effectiveness of thienopyridines (ticlopidine and clopidogrel) in patients with APANK, compared to other antiplatelet agents, can probably be explained by the fact that due to the large extent of atherosclerotic lesions and impaired rheological properties of the blood, the content of ADP released from erythrocytes is significantly increased. Thus, blockade of this platelet activation pathway may result in a greater reduction in the risk of blood clots.

Aspirin in patients with diabetes mellitus

Clinical manifestations of atherothrombosis are the direct cause of death in 80% of patients with diabetes mellitus, of which three quarters of cases are associated with ischemic heart disease. An analysis of nine studies in 4961 patients with diabetes showed that the reduction in the risk of developing vascular complications during antiplatelet therapy was only 7.8%, which is significantly less than among other high-risk patients (22%) [1]. The use of clopidogrel in patients with diabetes mellitus in the CAPRIE study allowed an additional avoidance of 21 vascular events in 1000 patients per year, and 38 in those requiring insulin, compared with aspirin [38]. Taking antiplatelet agents does not increase the risk of hemorrhages in the vitreous body and retina in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Aspirin during coronary artery bypass surgery

Prescribing aspirin in patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) can reduce the incidence of graft thrombosis by 50% [17]. However, until recently, there was no evidence of a positive effect of antithrombotic therapy on the risk of developing vascular events in these patients [1]. The majority of patients undergoing CABG are currently high-risk patients, in whom the incidence of postoperative complications exceeds 15% [18]. Moreover, these complications are associated not only with impaired cardiac function, but also with ischemia of the brain, kidneys, and intestines. A limitation to the use of antithrombotic drugs in the postoperative period may be the increased risk of hemorrhagic complications. In 2002, the results of a large, multicenter, prospective study [19] were published examining the effect of aspirin on the incidence of vascular events in more than 5000 patients undergoing CABG. In patients who received aspirin at a dose of 75-650 mg/day within 48 hours of revascularization, there was a significant reduction in the incidence of postoperative death, compared with those who were not prescribed aspirin (1.3% and 4%, p < 0.001, respectively). Taking aspirin was accompanied by a statistically significant reduction in the risk of developing myocardial infarction by 48%, stroke by 50%, renal failure by 74%, and intestinal infarction by 62%. Aspirin did not increase the risk of bleeding, gastrointestinal disorders, infection, or slow down the postoperative healing process. It should be noted that a significant decrease in the number of fatal and non-fatal complications was observed only among patients who received aspirin in the first 48 hours after surgery. Administration of the drug after 48 hours was accompanied by a non-significant reduction in postoperative mortality by 27%. There was also no dose-dependent antithrombotic effect of aspirin. This study confirmed the leading role of activation of the platelet component of hemostasis in the occurrence of dysfunction of vital organs in the postoperative period, as well as the fact that early administration of aspirin can be considered effective and safe in patients who have undergone CABG. However, among patients after CABG there is a high percentage of people with aspirin resistance, which may be due to the activation of cyclooxygenase-2 due to reparative processes.

Aspirin resistance

An important problem that attracts the interest of researchers is aspirin resistance, which is characterized by the inability of aspirin to prevent the development of thrombotic complications, as well as to adequately suppress the production of thromboxane A2. Resistance to aspirin is detected in 5-45% of patients, both among various groups of patients and in healthy individuals. Among the reasons for resistance to aspirin are considered: polymorphism and/or mutation of the cyclooxygenase-1 gene, the possibility of formation of thromboxane A2 in macrophages and endothelial cells via cyclooxygenase-2, polymorphism IIb/IIIa of platelet receptors, activation of platelets through other pathways that are not blocked by aspirin [20 ]. Unfortunately, very few studies have been conducted to evaluate the prognostic significance of laboratory-based aspirin resistance. Thus, the HOPE study showed that in patients with high urinary excretion of 11-dehydrothromboxane B2 (a stable metabolite of thromboxane A2), the risk of developing cardiovascular events was 1.8 times higher [21]. To date, no unified methods have been developed for assessing the antiplatelet effect of aspirin. Nevertheless, further study of this problem will contribute to the development of an individual approach to antithrombotic therapy, as well as increasing its effectiveness.

Aspirin and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease

The practice of primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases over the past 30 years has reduced mortality from coronary causes by 25% [22]. Aspirin is the only antithrombotic drug currently used for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. In what cases, when correcting major cardiovascular risk factors, is aspirin prescribed?

Suggestions that regular use of aspirin can reduce the risk of developing myocardial infarction and death from coronary causes appeared back in the 70s. [23-25]. Two large prospective studies were conducted in which aspirin was prescribed to female nurses without a previous coronary history and to patients with suspected CAD [26, 27]. The first study, which lasted for six years, was conducted on 87,678 women aged 34 to 65 years who regularly took one to six aspirin tablets per week [26]. The risk of non-fatal MI and coronary death was significantly reduced by 25%, in addition, there was a trend towards a decrease in death from vascular causes and the number of major vascular complications. It is interesting to note that the positive effect of aspirin was not pronounced in women under 50 years of age - the ratio of the number of vascular events among those who received and did not receive aspirin was 22 and 23 per 100 thousand. At the same time, in older age groups, the effectiveness of aspirin was significantly higher . Among women from 50 to 54 years of age, the incidence of vascular events in those who took and did not take aspirin was 62 and 121 per 100 thousand, and in the group from 55 years of age and above - 112 and 165 per 100 thousand, respectively. In another open-label study [27], among individuals in whom the diagnosis of coronary artery disease was not confirmed, aspirin administration reduced the risk of death in the group aged 60 years and above (5 and 8%, in those receiving and not receiving aspirin, respectively).

To date, there are data from five large controlled studies that examined the use of aspirin for primary prevention. These are American and English studies of doctors, Thrombosis Prevention Trial (TPT), Hypertension Optimal Treatment Study (HOT), Primary Prevention Project (PPP) [28-32].

A combined analysis of the results of American and English studies of doctors [33] revealed a significant reduction in the risk of non-fatal MI by 32%, and all vascular events by 13%. There was no significant effect of aspirin on overall and cardiovascular mortality, but there was a trend towards an increase in the incidence of non-fatal stroke. The dose of aspirin in these studies was 325 mg every other day and 500 mg/day, respectively. In an American study, aspirin administration avoided 4.4 myocardial infarctions per 1000 patients treated with this drug per year in the “older” age group, while the overall reduction was 1.9 per 1000 per year [28]. The effect of aspirin was also greater in individuals with diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, smokers and those leading a sedentary lifestyle [28].

In the TPT and HOT studies, aspirin was given at significantly lower doses of 75 mg/day. The TPT [30] included individuals at high risk of developing cardiovascular disease who received warfarin or aspirin monotherapy, a combination of warfarin and aspirin, and placebo. The number of fatal and non-fatal cases of coronary death during therapy with warfarin and aspirin decreased approximately equally - by 20%, while the effect of warfarin was mainly associated with a decrease in the incidence of fatal cases of coronary artery disease (39%), and aspirin - non-fatal cases (32%). The effect of aspirin was significantly greater in subjects with baseline systolic blood pressure ≤ 130 mm. rt. Art. (45% risk reduction) and was practically not observed with blood pressure ≥ 145 mm. rt. Art. (-6%) [34].

The HOT study was devoted to studying the effectiveness and safety of aspirin in patients with arterial hypertension under the conditions of selected antihypertensive therapy [31]. Prescription of aspirin reduced the risk of MI by 36%, and the total number of cardiovascular complications (MI, stroke, cardiovascular death) by 15%. The lowest incidence of cardiovascular events was observed when the mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) reached 82.6 mm. rt. Art. the minimum risk of cardiovascular mortality at a DBP level is 86.5 mm. rt. Art. Further reductions in DBP were also safe. In patients with diabetes mellitus, the incidence of cardiovascular events on aspirin therapy decreased by 51% when DBP reached 80 mm. rt. Art. As in TPT, the HOT study did not show an increase in the total number of strokes with aspirin therapy.

Somewhat different are the results of the RRR study published in 2001 [32], in which aspirin was prescribed at a dose of 100 mg/day to patients with one or more risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The risk of developing MI and stroke decreased approximately equally - by 31 and 33%. There was a significant reduction in cardiovascular mortality by 44%, and all cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI and stroke, transient cerebrovascular accidents, stable angina, peripheral atherosclerosis) - by 23%.

In 2002, the results of a meta-analysis of five controlled trials on the primary prevention of cardiovascular events were published, which included more than 60 thousand patients [35]. It has been shown that the use of aspirin significantly reduces the risk of developing a first myocardial infarction by 32%, and the total number of vascular events by 15%. There was no statistically significant effect of aspirin on total mortality or total strokes, but the numbers were small in each of the studies pooled in the meta-analysis. The incidence of hemorrhagic stroke and gastrointestinal bleeding was higher in patients receiving aspirin. A meta-analysis of primary prevention studies found that aspirin avoided six to 20 myocardial infarctions in 1,000 patients with a 5% risk of vascular events over five years, but could cause between 0 and 2 more heart attacks. hemorrhagic strokes and two to four gastrointestinal bleedings [35].

Based on available data, taking aspirin for the purpose of primary prevention of cardiovascular events is recommended for patients with a risk of developing MI and ischemic stroke that exceeds the risk of possible complications (bleeding, hemorrhagic stroke, gastrointestinal disorders) [36, 37]. This group includes men and women over 50 years of age with at least one risk factor for coronary artery disease (hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, smoking, arterial hypertension). When prescribing aspirin to patients with arterial hypertension, blood pressure correction is necessary (maintaining DBP ≤ 85 mm Hg). The dose of aspirin considered effective for primary prevention is 75 mg/day.

The history of aspirin use goes back more than 100 years. Today, aspirin remains the most accessible and widely used antiplatelet drug used for both secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. The clinical effectiveness of aspirin is confirmed by the results of numerous, controlled studies and meta-analyses. Importantly, the effectiveness of aspirin in reducing the cumulative incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular mortality in high-risk groups remains independent of the emergence of new meta-analyses. Aspirin therapy can be considered as the standard of antithrombotic therapy, which is prescribed to all patients at high risk of developing vascular complications in the absence of contraindications. Of course, the prescription of aspirin, which blocks one pathway of platelet activation associated with inhibition of cyclooxygenase and the formation of thromboxane A2, does not help solve all the problems that arise during antithrombotic therapy. An important problem is aspirin resistance, which has been identified in a number of patients. Currently, there is an active search for antithrombotic drugs with different mechanisms of action that can enhance aspirin therapy in high-risk patients. The results of the CURE, CURE-PCI, CREDO studies convincingly demonstrated that taking a combination of aspirin and Plavix (clopidogrel) for 9-12 months leads to an additional reduction in the risk of developing vascular episodes in patients with ACS and after coronary balloon angioplasty. The effectiveness of platelet receptor IIb/IIIa inhibitors in interventions on the coronary arteries has also been demonstrated while taking aspirin. Antiplatelet drugs do not affect the coagulation cascade, the activation of which ultimately leads to increased thrombo- and fibrin formation, therefore, the combination of aspirin with indirect anticoagulants, an oral thrombin inhibitor - ximelagatran, as well as a newly created drug - seems promising in terms of preventing cardiovascular episodes. inhibitor of the factor VII/tissue factor complex.

Literature

- McConnel H. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. Br. Med. J. 2002; 324: 71-86.

- Dutch TIA Trial Study Group. A comparison of two doses of aspirin (30 mg vs. 283 mg a day) in patients after a transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke. N.Engl. J. Med. 1991; 325: 1261-66.

- Farrel B., Godwin J. et. al. The United Kingdom transient ischemic attack (UK-TIA) aspirin trial: final results. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Phychiatry 1991; 54: 1044-54.

- Taylor DW, Barnett HJM et. al. Low-dose and high-dose acetylsalicylic acid for patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy: randomized controlled trial. Lancet 1999; 353:2179-83.

- CAST (Chinese Acute Stroke Trial). Collaborative Study Group. CAST: randomized placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischemic stroke. Lancet 1997; 349:1641-9.

- International Stroke Trial Study Group. The International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomized trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischemic stroke. Lancet 1997; 349:1569-81.

- Laupacis A., Albers G., Dalen J. et. al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Chest 1998; 114:579S-89S.

- Segal JB, McNamara RL, Miller MR et. al. Prevention of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of trials of anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs. J.Gen. Intern. Med 2000; 15: 56-67.

- Hart RG, Benavente O., McBride R. et. al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. ANN. Intern. Med. 1999; 131: 492-501.

- Albers G., Dalen J., Laupacis A. et. al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Chest 2001; 119: 194S-206S.

- Juul-Moller S., Edvardsson N., Jahnmatz B. et al. Double-blind trial of aspirin in primary prevention of myocardial infarction in patients with stable chronic angina pectoris. Lancet 1992; 340: 1421-5.

- Dormandy J., Mahir M., Ascady G. et al. Fate of the patient with chronic leg ischemia. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1989; 30 (1): 50-57.

- Smith GD, Shipley MJ, Rose G. Intermittent claudication, heart disease risk factors, and mortality: The Whitehall Study. Circulation 1990; 82(6): 1925-31.

- Guillot F. Atherothrombosis as a marker for disseminated atherosclerosis and a predictor of further ischemic events. Eur. Heart J 1999; 1(A): 14-26.

- Hertzer NR, Beven EG, Young JR et al. Coronary artery disease in peripheral vascular patients. A classification of 1000 coronary angiograms and results of surgical management. Ann. Surg. 1984; 199: 223-33.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomized, blinded trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996; 348: 1329-39.

- Antiplatelet Trialist'Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomized trials of antiplatelet therapy - II: maintenance of vascular graft or arterial patency by antiplatelet therapy. Br. Med. J. 1994; 308: 159-68.

- Mangano DT Cardiovascular morbidity and CABG surgery — a perspective: epidemiology, costs, and potential therapeutic solutions. J.Card. Surg. 1995; 10: Suppl: 366-8.

- Mangano DT Aspirin and mortality from coronary bypass surgery. N.Engl. J. Med. 2002; 347:1309-17.

- McKee SA, Sane DC, Deliargyris EN Aspirin resistance in cardiovascular disease: a review of prevalence, mechanisms, and clinical significance. Thromb. Haemost. 2002; 88: 711-5.

- Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J, Weitz JI et al. Aspirin resistance and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death in patients at high risk of cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation 2002; 105: 1650-5.

- Hunink MG, Goldman L, Tosteson AN et. al. The recent decline in mortality from coronary heart disease, 1980-1990: the effect of secular trends in risk factors and treatment. JAMA 1997; 277:535-42.

- Hennekens CH, Karlson LK, Rosner B. A case-control study of regular aspirin use and coronary deaths. Circulation 1978; 58: 35-38.

- Hammond EC, Garfinkel L. Aspirin and coronary heart disease: findings from a prospective study. Br. Med. J. 1975; 2: 269-71.

- Jick H., Miettinen OS Regular aspirin use and myocardial infarction. Br. Med. J. 1976; 1: 1057-8.

- Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA et. al. A prospective study of aspirin use and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA 1991; 266:521-27.

- Gum PA, Thamilarasan M, Watanabe J et. al. Aspirin use and all-cause mortality among patients being evaluated for known or suspected coronary artery disease: a propensity analysis. JAMA 2001; 286: 1187-1194.

- Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians' Health Study. Steering Committee of the Physicians' Health Study Research Group. N.Engl. J. Med. 1989; 321: 129-35.

- Peto R., Gray R., Collins R. et al. Randomized trial of prophylactic daily aspirin in British male doctors. Br. Med. J. 1988; 296: 313-6.

- Thrombosis prevention trial: randomized trial of low-intensity oral anticoagulation with warfarin and low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of ischemic heart disease in men at increased risk. The Medical Research Council's General Practice Research Framework. Lancet 1998; 351: 233-41.

- Hansson L., Zanchetti A., Carruthers SG et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomized trial. Lancet 1988; 351: 1766-62.

- Collaborative Group of the Primary Prevention Project. Low-dose aspirin and vitamin E in people at cardiovascular risk: a randomized trial in general practice. Lancet 2001; 357:89-95.

- Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Sandercock P. et al. Aspirin and other antiplatelet agents in the secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 1989; 80: 749-56.

- Meade TW, Brennan PJ Determination of who may derive the most benefit from aspirin in primary prevention: subgroup results from a randomized controlled trial. Br. Med. J. 2000; 321: 13-17.

- Hayden M., Pignone M., Phillips C., Mulrow C. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: A summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. ANN. Intern. Med. 2002; 136: 161-72.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: Recommendation and rationale. ANN. Intern. Med. 2002; 136: 157-160.

- Cairns J., Theroux P., Lewis D. et al. Antithrombotic agents in coronary artery disease. Chest 2001; 119: 228S-252S.

- Bhatt DLJ Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000; 35(Suppl A): 409.

P. S. Laguta, Candidate of Medical Sciences E. P. Panchenko, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Research Institute of Cardiology named after. A. L. Myasnikova RKNPK Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation

Thinning agents

The most affordable ones today are drugs based on acetylsalicylic acid, better known as Aspirin. Such medications are common in pharmacies and cost little. Due to the fact that acetylsalicylic acid carries certain risks for the hematopoietic system and can cause gastric bleeding or ulcers, medicine has actively begun to work on the creation of drugs free from aspirin. Such dosage forms are available in pharmacies today. This group of drugs is divided into two subgroups

- antiplatelet agents that prevent blood cells from sticking together.

- anticoagulants, which prevent the formation of fibrin clots during coagulation.

Such drugs can be prescribed not only to older people to thin the blood, but also to pregnant women, in order to ensure the best blood flow between mother and fetus. A course of taking medications from this group saturates the blood with oxygen, which is very important for the developing fetus.

How can aspirin prevent a heart attack?

Aspirin prevents blood clotting. When bleeding, special blood cells - platelets - seal the hole in the blood vessel and stop the bleeding.

Similar processes involving platelets can also occur in the vessels that supply the heart with blood. If the coronary vessels are affected by atherosclerosis, a blood clot may form in the area where atherosclerotic plaques form. If a clot blocks an artery, blood will stop flowing to the heart. This will cause a heart attack. Aspirin reduces the ability of platelets to stick together and form a blood clot. And therefore can prevent a heart attack.

Your doctor may suggest daily therapy with acetylsalicylic acid if:

- Have you already had a heart attack or stroke?

- You have not had a heart attack, but you have had coronary artery bypass surgery, or have chest pain due to coronary artery disease (angina), or have a stent placed in a coronary artery

- You are at high risk of having a heart attack if you have at least 2 of the following 4 symptoms: diabetes, age over 50, high blood pressure, and a smoker.

Prophylactic aspirin is indicated for people aged 50 to 59 years if there is no risk of bleeding and if the person has a greater than 10% risk of heart attack or stroke within the next 10 years. For adults younger than 50 years and older than 60 years, more research is needed to determine the benefits and risks of daily aspirin therapy.

Today, there is ongoing debate about the benefits of aspirin for people who have not had a history of a heart attack. But most experts agree that the higher your risk of developing a heart attack, the greater the chance that the benefits of taking a daily aspirin tablet will outweigh the harm of developing complications from aspirin therapy.

Antiplatelet agents

The main indications for prescribing antiplatelet agents are:

- Cardiac lesions that have led to a lack of blood circulation in the myocardium or completely deprived it of blood flow.

- Ischemic heart lesions, especially those accompanied by tissue necrosis.

- Arrhythmia.

- Tachycardia.

- Prevention of thrombosis in patients who have had a stroke.

- Heart surgery or interventions to restore the circulatory system (stenting).

- Arterial damage.

The cost of such medicines is slightly higher than those containing acetylsalicylic acid. As a rule, such medications are taken in a course, which ensures high rheological properties of the blood constantly.

Preparations without acetylsalicylic acid

Patients over 18 years of age who do not have problems with the gastrointestinal tract are safely prescribed medications containing aspirin. Especially if the duration of use does not exceed 5-7 days. In other cases, it is recommended to avoid consuming large doses of acetylsalicylic acid, especially in older patients.

The list of antiplatelet agents that do not contain aspirin includes:

- Curantil with the active ingredient dipyridamole.

- Ticlid, whose action is based on ticlodipine.

- Plavix, blood thinners thanks to cropidogrel.

- Brilint, which is based on the active ingredient ticagrelor.

- Efficient, working thanks to prasugrel included in the composition

- Pletax with the active ingredient cilostazol.

- Trental, whose action is due to pentoxifylline.

A wide selection of drugs allows a competent doctor to select an individual course of therapy for each patient, based on possible side effects and the presence of chronic diseases in the patient.

Aspirin dose

Depending on your indication, your doctor will help you find the right dose of acetylsalicylic acid for you.

As a rule, no more than 85 mg of acetylsalicylic acid per day is prescribed for daily preventive use, but in some cases individual dosage is possible. For people who have had a heart attack or have a stent in a coronary artery, it is very important to take aspirin and other blood thinning medications exactly as your doctor recommends. For them, stopping daily therapy with acetylsalicylic acid can have life-threatening consequences: provoke the development of a blood clot and lead to a heart attack. For such people, taking any medications that reduce the effectiveness of acetylsalicylic acid must be agreed with their doctor.

When taking aspirin daily, you should be careful when taking other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): ibuprofen, diclofenac, indomethacin, etc. Regular use of NSAIDs may increase the risk of bleeding.

If you need a single dose of ibuprofen, take it two hours after the aspirin. If you need to take ibuprofen or other NSAIDs long-term, talk to your doctor about alternative medications that will not interfere with your daily acetylsalicylic acid therapy.

Chimes with depyridamole

This drug can be called mandatory for use by pregnant women after the 20th week of gestation. In the annotation you can read a phrase warning about possible risks. If a local obstetrician-gynecologist has prescribed a course of Curantil, this indicates that the woman is not at risk and can safely take a blood thinner.

The medicine accelerates the blood, allowing the expectant mother to share nutrients with the child. Taking Curantil will ensure the full development of the unborn baby.

Description of the drug Tiklpid

Taking Triclid can reduce the aggregation of blood platelets and significantly reduce the viscosity of biological fluid. Violation of the prescribed treatment regimen and overdose can lead to the following adverse reactions:

- bleeding;

- lack of platelets necessary for natural blockage of damaged areas of arteries, vessels and tissues;

- decreased levels of white blood cells;

- abdominal pain;

- diarrhea.

In case of severe blood thickening, the drug is prescribed for a long course, and the patient’s condition is regularly monitored. When the rheology of the main biological fluid is restored, the drug can be discontinued. However, stopping the medication does not replace regular blood quality testing.