Possibilities of combination therapy for arterial hypertension

As is known, effective antihypertensive therapy reduces the incidence of cerebral stroke by 42% and acute myocardial infarction by 14% in patients with hypertension.

Currently, there are a fairly large number of effective antihypertensive drugs - selective B1-blockers, A1-blockers, diuretics, calcium antagonists, ACE inhibitors, and in recent years - angiotensin II receptor blockers. Various clinical studies have shown that all of the listed classes of antihypertensive drugs reduce high blood pressure almost equally and can be used as first-line drugs (THOMS study), but in practice the situation is far from so clear. It was shown (Merand J., 1992) that among 11,613 patients with arterial hypertension, an adequate reduction in diastolic pressure was achieved only in 37% of cases, while the authors believe that one of the reasons for the unsatisfactory result was monotherapy, which did not allow blocking the various mechanisms responsible for rise in blood pressure. Thus, in observations of 1292 patients with hypertension (men) who received monotherapy for 1 year (Matterson BJ, 1995) with an initial diastolic pressure of 95-109 mm Hg. values of this indicator below 90 mm were obtained only in 40-60% of patients (depending on the drug used). The last circumstance is especially important and, apparently, can be explained by the fact that in response to taking one antihypertensive drug in patients with hypertension, the mechanisms that counteract the decrease in blood pressure are “launched” (or increased in activity). So, for example, when calcium antagonists are prescribed, the sympathoadrenal system is activated and fluid is retained in the body, and when diuretics are prescribed, the depletion of sodium “reserves” stimulates the renin-angiotensin system and activates the sympathoadrenal system. Long-term use of B-blockers leads to increased sympathetic tone of peripheral vessels (and to vasoconstriction); ACE inhibitors can increase (via a feedback mechanism) renin secretion. It is likely that this incomplete list will subsequently be supplemented by other mechanisms responsible for the occurrence of the “escape” effect. In this regard, the simultaneous use of two (and sometimes three) antihypertensive drugs with different mechanisms of action seems quite promising. Thus, this approach is justified by the following considerations:

- simultaneous use of drugs from two different pharmacological groups more actively reduces blood pressure due to the fact that there is an effect on various pathogenetic mechanisms of hypertension;

- the combined use of lower doses of two drugs acting on different regulatory systems will allow for better control of blood pressure, given the heterogeneity of the response of hypertensive patients to antihypertensive drugs;

- prescribing a second drug may weaken or balance the triggering of mechanisms to counteract the decrease in blood pressure that occurs when prescribing one drug;

- a sustained decrease in blood pressure can be achieved with smaller doses of two drugs than with monotherapy;

- smaller doses allow you to avoid dose-dependent side effects, the likelihood of which is higher with a larger dose of a particular drug (during monotherapy);

- the use of two drugs can to a greater extent prevent target organ damage (heart, kidneys) caused by hypertension;

- prescribing a second drug can to a certain extent reduce (and even completely eliminate) the undesirable effects caused by the first (even if quite effective) drug;

Given the presence of at least six groups of antihypertensive drugs, it is possible to create a fairly large number of combinations, however, in practice it is advisable to use only a few of them.

B-blocker in combination with a diuretic

It is known that a B-blocker, in addition to peripheral vasoconstriction (most pronounced in non-selective B-blockers), can increase sodium retention by the kidneys, and therefore its combination with a diuretic is completely justified. In this case, various types of combinations are possible: taking a diuretic daily or taking a diuretic 1-2 times a week. Preference should be given to thiazide diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone). Daily intake of a diuretic can range from 6.25-12.5 mg, but if a non-daily dose is prescribed, the dose is usually increased to 25 mg (1-2 times a week). These doses are to a certain extent approximate; in each specific case, the dose of the diuretic can be changed. Fixed doses of antihypertensive components are very convenient, the non-extended-release B-blocker pindolol (Wisken) at a dose of 10 mg was combined with the diuretic clopamide (5 mg) - the drug "Viskaldix", the selective B-blocker atenolol at a dose of 100 mg with chlorthalidone (25 mg) - drugs "tenoric" and "tenoretic".

Calcium antagonist in combination with a B-blocker

The hypotensive effect of calcium antagonists of all three generations is beyond doubt. However, peripheral vasodilation can cause quite pronounced activation of the sympathetic nervous system (which in itself is a pressor factor) and reflex tachycardia, which is poorly tolerated by patients. In this situation, the addition of a B-blocker not only has an additional hypotensive effect (which may allow the dose of the calcium antagonist to be reduced), but also has a “corrective” effect, reducing (and completely eliminating) tachycardia. The addition of a B-blocker is especially appropriate for drugs such as nifedipine and felodipine, less often for isradipine and very rarely for amlodipine. Currently, the most well studied fixed combination of felodipine (5 or 10 mg) and the cardioselective B-blocker metoprolol (50 or 100 mg) is the drug Logimax. This combination has been shown to be more effective than each of its components separately. A less well-known combination of nifedipine (20 mg) and atenolol (50 mg) is the drug Niften. At the same time, isoptin should not be combined with a B-blocker (due to the pronounced synergism of action).

Calcium antagonist in combination with a diuretic

As you know, one of the side effects of calcium antagonists (of almost all generations) is swelling of the ankles and legs (due to vasodilation?). The addition of diuretics (thiazides) helps to get rid of this undesirable phenomenon, while the doses of diuretics are not very large.

ACE inhibitors in combination with a diuretic

ACE inhibitors themselves are very effective in most patients with hypertension, but the addition of a diuretic significantly enhances the hypotensive effect. In addition, such a combination is justified in patients in whom an ACE inhibitor reduces blood pressure well, but causes side effects such as cough (which requires a dose reduction). Finally, this combination is especially effective in older people, especially if hypertension is combined with symptoms of heart failure. In Russia, such combinations as “korenitek” (enalapril 10 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg), “enap-N” (enalapril and hydrochlorothiazide in the same dosages), “caposide” (captopril 50 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg) have become widespread ). The average dose is 1 2 tablets 1 time per day (regardless of meals).

ACE inhibitor in combination with a calcium antagonist

This combination is fundamentally new. It has been shown that it produces significantly fewer side effects than each of its components separately. In 1994 In Europe, the Knoll company released the drug Tarka, which is a combination of a new generation ACEI - trandolapril (at a dose of 1 or 2 mg) and verapamil-SR (retarded form) at a dose of 180 mg.

Antigen II receptor blockers and diuretic

A fundamentally new class of drugs - angiotensin II receptor blockers (AT-II) - "Cozaar" (losarten), "Diovan" (valsartan) showed high antihypertensive activity comparable to ACE inhibitors. However, probably the desire to obtain a stronger effect led to the creation of a combination drug, Gizaar (losartan at a dose of 50 mg and hydrochlorothiazide at a dose of 12.5 mg). The first experience of its use shows undoubted advantages over monotherapy with losartan alone.

The use of combination therapy using drugs with fixed doses (two drugs in one tablet) has a number of advantages: for the patient - ease of dosing, convenience of a single dose; for the doctor there are also a number of positive aspects in the form of confidence in the patient’s desire to follow the prescribed recommendations (compliance), the ability to manage with smaller doses of the drugs included in the tablet, and therefore a lower likelihood of dose-dependent side effects.

Thus, at the present stage of views on the treatment of hypertension, the principle of combination therapy should be recognized as a priority, although this does not mean that in a certain category of patients monotherapy is impossible, in particular in young people in the absence of target organ damage and good tolerability prescribed drugs.

Combined antihypertensive therapy: current status

Hypertension is a hemodynamic disorder by definition, and increased peripheral vascular resistance is a distinctive hemodynamic feature of elevated blood pressure. Understanding of this fact led to the discovery and development of a special class of vasodilators with a targeted mechanism of action, although many of the previously used antihypertensive drugs also had a vasodilating effect, for example, by blocking the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. The first nonspecific vasodilator was hydralazine, followed by vasodilators blocking calcium channels of vascular smooth muscle cells (calcium antagonists - AK), postsynaptic α-adrenergic receptors of peripheral neurons of the sympathetic nervous system (α-blockers) and blockers of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) ( angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs); finally, the latest to appear are direct renin inhibitors (DRIs). The vasodilating effect is also inherent in thiazide diuretics (TD), which, by reducing the sodium content in vascular smooth muscle cells, reduce their sensitivity to vasopressors - catecholamines, etc. When using antihypertensive drugs in a heterogeneous population of patients with hypertension, the selectivity of the active substances and their other features lead to an unpredictable decrease in blood pressure in each individual patient. For example, prescribing an ACE inhibitor to a patient with hyperactivation of the RAAS due to renal artery stenosis will lead to a significant decrease in blood pressure and renal dysfunction [2]. In turn, the prescription of ACE inhibitors to elderly people and people of the black race (who in most cases have a reduced level of RAAS activity) will lead to only a slight decrease in blood pressure [3]. Most often, the “phenotype” of hypertension in a particular patient remains unspecified. A recent meta-analysis of 354 placebo-controlled studies of different antihypertensive monotherapy regimens in unselected hypertensive patients (n=56,000) showed a mean (placebo-adjusted) reduction in systolic blood pressure of 9.1 mm Hg. and diastolic blood pressure – by 5.5 mm Hg. [4]. These average values hide a wide range of individual responses to antihypertensive therapy - from a decrease in SBP by 20–30 mmHg. and until there is a complete lack of effect, and sometimes even a slight increase in blood pressure [5]. The second factor that determines the individual response to antihypertensive monotherapy is individual differences in blood pressure counter-regulation systems activated in response to a decrease in its level. In some cases, such a reaction can completely compensate for the decrease in blood pressure. Thus, the use of antihypertensive monotherapy does not always give a satisfactory result. What should be the next step in a situation like this? Should the dose be increased, the drug changed, or a combination of antihypertensive agents used? Rationale for the use of combination antihypertensive therapy The rationale for the use of combination therapy for hypertension is quite obvious. Firstly, in contrast to blindly prescribed monotherapy, a combination of drugs acting on different blood pressure regulation systems significantly increases the likelihood of its effective reduction. Secondly, prescribing a combination of drugs can be regarded as an attempt to block the activation of counter-regulatory systems that counteract the decrease in blood pressure during the use of monotherapy (Fig. 1). Thirdly, a significant part of the population of patients with hypertension suffers from so-called moderate or severe hypertension (stage 2) [6], this group includes patients with systolic blood pressure more than 160 mm Hg. and/or diastolic blood pressure more than 100 mm Hg, which is about 15–20% of all patients with hypertension. These patients are at the highest risk of cardiovascular events. Increase in blood pressure for every 20 mm Hg. doubles the risk of such events. The risk of hypertension increases with age, and the proportion of patients with stage 2 hypertension also increases. Age is also associated with an increase in the proportion of patients with isolated systolic hypertension, which causes loss of vascular elasticity and an increase in vascular resistance. Despite some differences in recommendations, in some of them combination treatment is considered first-line therapy, although only under certain conditions. Such a place for combination therapy is logical due to the risks of severe hypertension, recognition of the inevitability of using double (and sometimes triple) therapy to achieve target blood pressure values less than 140/90 mm Hg. and the need to quickly reduce blood pressure to a more acceptable level to reduce existing risks. For systolic blood pressure 20 mmHg above target and/or diastolic blood pressure 10 mmHg above target, the US Joint National Committee on the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC–7) recommends start antihypertensive therapy with a combination of two drugs. Similar recommendations are contained in the latest Russian guidelines, and the recommendation for the use of first-line combination antihypertensive therapy also applies to patients with lower blood pressure levels who have multiple risk factors, target organ damage, diabetes mellitus, kidney disease or associated cardiovascular diseases [ 7]. There are concerns that the use of more than one antihypertensive drug at the beginning of treatment may in some cases provoke clinically significant hypotension and increase the risk of coronary events. Analysis of studies on the treatment of hypertension has provided some evidence of the existence of a J-shaped relationship between a decrease in blood pressure and cardiovascular risk, however, apparently, this applies to patients at high risk, including those with known coronary artery disease, when a pronounced decrease in blood pressure may lead to deterioration of myocardial perfusion [8]. Patients with uncomplicated hypertension tolerate low blood pressure values satisfactorily, as, for example, in the Systolic hypertension in Elderly study, where in the active treatment group it was possible to reduce systolic blood pressure to 60 mm Hg. [9]. Ongoing studies designed to compare initiation of antihypertensive therapy with dual and sequential monotherapy will evaluate the safety of the new approach. Fourth, compared to monotherapy, combination therapy can achieve a reduction in blood pressure variability [10]. Additional analysis of several randomized trials showed that visit-to-visit systolic BP variability is a strong and independent of mean BP predictor of myocardial infarction and stroke [18]. It is noteworthy that ACs and diuretics showed the greatest effectiveness in reducing such blood pressure variability and the risk of stroke. β-blockers, on the contrary, increased systolic blood pressure variability in a dose-dependent manner and showed the least effectiveness in preventing stroke. The addition of a calcium inhibitor or, to a lesser extent, a diuretic to a RAAS inhibitor reduces systolic blood pressure variability, which is an additional argument in support of combination therapy. Combinations of drugs There are 7 classes of antihypertensive drugs, each of which includes several representatives, so there are a large number of combinations (Table 1). Combinations will be presented below according to their division into rational (preferred), possible (acceptable) and unacceptable or ineffective. Assignment of a combination to a particular group depends on outcome data, antihypertensive efficacy, safety and tolerability. Rational (preferred) combinations RAAS inhibitors and diuretics. Currently, this combination is most often used in clinical practice. A significant number of studies with a factorial design have shown additional reductions in BP when using a combination of TD and ACEI, ARB or PIR. Diuretics reduce the volume of intravascular fluid, activate the RAAS, which inhibits the excretion of salt and water, and also counteracts vasodilation. Adding a RAAS inhibitor to a diuretic weakens the effect of this counterregulatory mechanism. In addition, the use of a diuretic can cause hypokalemia and impaired glucose tolerance, and RAAS blockers can reduce this undesirable effect. It has been shown that chlorthalidone is more effective in lowering blood pressure than hydrochlorothiazide, because has a longer duration of action, so chlorthalidone should be preferred as the second component in combination with a RAAS inhibitor. Most RAAS inhibitors are available in fixed combination with hydrochlorothiazide. A study of hypertension in elderly patients (over 80 years of age) (HYVET, Hypertension in the Very Elderly) was recently completed, which assessed the effectiveness of the thiazide-like diuretic indapamide. The ACE inhibitor perindopril was added to this diuretic to enhance the antihypertensive effect in 75% of patients. A 30% reduction in stroke and a 64% reduction in heart failure was shown with this combination compared with placebo.

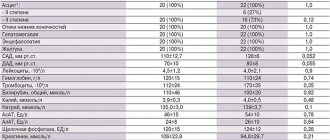

Using a combination of an ACE inhibitor and a diuretic, the EPIGRAF project was carried out under the auspices of the All-Russian Scientific Society of Cardiology. This project consisted of two multicenter studies, EPIGRAPH-1 and EPIGRAPH-2. This project is valuable in that it contributed to the creation of a non-fixed combination of Enzix (“Stada”), containing two drugs in one blister - enalapril (ACE inhibitor) and indapamide (diuretic), which allows, if necessary, to change their dosages and correlate the time of administration with the circadian rhythm of blood pressure , have 2 drugs in one package, rather than using two separate ones. The drug is available in three forms: Enzix - 10 mg enalapril and 2.5 mg indapamide; Enzix Duo – 10 mg enalapril and 2.5 mg indapamide + 10 mg enalapril; Enzix Duo forte – 20 mg enalapril and 2.5 mg indapamide + 20 mg enalapril. Different dosages allow you to adjust therapy depending on the severity and risk of hypertension and drug tolerability. A study conducted in Ukraine examined the effect of long-term therapy with a non-fixed combination of enalapril and indapamide in 1 blister (Enzix, Enzix Duo) on the daily blood pressure profile and parameters of LV remodeling, its systolic and diastolic function, as well as the quality of life of patients with stable hypertension. The results of the study showed that in patients with hypertension, long-term use of a combination of enalapril and indapamide (Enzix, Enzix Duo) significantly improves the magnitude and speed of the morning rise in blood pressure and has a positive effect on blood pressure variability. Also, the data obtained indicated that long-term use of a non-fixed combination of enalapril and indapamide in 1 blister (Enzix, Enzix Duo) has a clear antihypertensive effect, leads to reverse development of LV remodeling and improvement of its diastolic function, improved quality of life along with a good safety profile and portability.

RAAS inhibitors and calcium antagonists. Combining AK with an ACE inhibitor, ARB or PIR can achieve additional reduction in blood pressure. Peripheral edema is a common dose-dependent adverse event observed with dihydropyridine CB monotherapy. The severity of this adverse effect can be reduced by adding a RAAS inhibitor to the AA. A recent meta-analysis found that ACEIs are more effective in this regard than ARBs [15]. According to the results of the ACCOMPLISH study (The Avoiding Cardiovascular Events through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension Trial), a fixed combination of the ACE inhibitor benazepril with the AC amlodipine is more effective in reducing morbidity and mortality than the fixed combination of an ACE inhibitor with hydrochlorothiazide [12]. Overall, ACEIs and ARBs showed similar reductions in endpoint rates, although it has been suggested that ACEIs are slightly more cardioprotective and ARBs are better at protecting against stroke. The international INVEST study compared two antihypertensive treatment regimens: verapamil, to which trandolapril was added when necessary, and atenolol, to which hydrochlorothiazide was added when necessary [16]. The study included 22,576 patients with hypertension with an established diagnosis of coronary artery disease; observation was carried out for 2.7 years. The primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular events was achieved in both groups at the same rate. Apparently, this can be explained by the fact that the disadvantages of the treatment regimen, which included a β-blocker for hypertension, were compensated by the advantages of β-blockers for coronary artery disease. b-blockers and diuretics. Not all experts consider this combination to be rational. At the same time, it has been shown that the addition of diuretics to β-blockers causes an increase in the antihypertensive effect in populations with low-renin hypertension. Although both classes of drugs have similar side effects in the form of impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes and sexual dysfunction, the actual clinical significance of “metabolic” side effects has been greatly exaggerated, and endpoint studies have shown that the use of such a combination leads to a decrease in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [11]. Possible (acceptable) combinations: Calcium channel blockers and diuretics. Most doctors do not always combine AKs with diuretics. However, in the VALUE study (Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation Trial), hydrochlorothiazide was added to amlodipine, when it was insufficiently effective, and this combination was well tolerated by patients, although in comparison with the valsartan group, the risk of diabetes mellitus and hyperkalemia increased [13]. However, the reduction in morbidity and mortality in the amlodipine group was no less than in the valsartan group. Calcium channel blockers and β-blockers. The combination of a β-blocker with a dihydropyridine AA has an additional effect on lowering blood pressure and is generally quite well tolerated. Conversely, β-blockers should not be combined with non-dihydropyridine CBs such as verapamil and diltiazem. The combination of the negative chronotropic effect of both classes of drugs can lead to the development of bradycardia or heart block, up to complete transverse, and to the death of the patient. Double blockade of calcium channels. A recent meta-analysis showed that the combination of a dihydropyridine AA with verapamil or diltiazem leads to an additional reduction in blood pressure without a significant increase in the incidence of adverse events [17]. Such combination therapy can be used in patients with documented angioedema while taking RAAS inhibitors, as well as in patients with severe renal failure, accompanied by a risk of hyperkalemia. However, there are currently no data on long-term safety and outcomes with such therapy. Double blockade of the RAAS. The use of this combination is based on enhancing the blood pressure-lowering effect, which has been proven in a number of studies. However, the significance of this combination has diminished due to unconfirmed safety in long-term studies. In the ONTARGET study, patients receiving combination therapy with telmisartan and ramipril experienced more adverse events, and the number of cardiovascular events, despite some additional reduction in blood pressure, did not decrease compared to monotherapy. Thus, such a combination in patients at high risk of adverse events does not make much sense. However, because blockade of the RAAS by ACE inhibitors or ARBs increases plasma renin activity, the addition of a direct renin inhibitor has been suggested to be effective. A double-blind study of the combination of aliskiren and ARBs, conducted in 1797 patients, revealed a small but statistically significant decrease in blood pressure. It is noteworthy that in an open-label, prospective, crossover study of patients with resistant hypertension, the aldosterone antagonist spironolactone was more effective in lowering blood pressure than dual blockade of the RAAS [18]. The use of a combination of PIR with an ACE inhibitor or ARB in the ALTITUDE (Aliskiren Trialin Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardiovascular and Renal Disease Endpoints) study, based on the results of an interim analysis in 2012 . turned out to be inappropriate due to an increased risk of adverse events, and the study was stopped early. Apparently, it is advisable to transfer combinations of ACE inhibitors with ARBs to the group of non-recommended combinations. Unacceptable and ineffective combinations RAAS blockers and β-blockers. A combination of these classes of drugs is often used in patients who have had a myocardial infarction, as well as in patients with heart failure, because they have been shown to reduce the incidence of reinfarction and improve survival. However, this combination does not provide any additional reduction in blood pressure compared to monotherapy with these drugs. Thus, using a combination of a RAAS inhibitor and a β-blocker for the treatment of hypertension as such is inappropriate. β-blockers and drugs with central antiadrenergic action. Combining beta blockers with centrally acting antiadrenergic drugs such as clonidine provides little or no additional blood pressure reduction. Moreover, when using such a combination, reactions with an excessive increase in blood pressure were even observed [19]. Other classes of drugs in combination therapy: α-blockers and spironolactone α-adrenergic receptor antagonists are widely used as adjunctive therapy to achieve target blood pressure values. The advent of extended-release dosage forms has improved the tolerability profile of these drugs. Data from an observational analysis of the ASCOT study (the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial) showed that doxazosin in the gastrointestinal therapeutic system, used as third line therapy, lowers blood pressure and causes a moderate decrease in serum lipids [20 ]. In contrast to earlier data from the ALLHAT (Antihypertensive and Lipid–Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial), doxazosin use in the ASCOT trial did not show an association with an increased incidence of heart failure. Therapy consisting of 4 antihypertensive drugs is often required in patients who are resistant to treatment with drugs at maximum doses or triple antihypertensive therapy, including a RAAS blocker, a calcium antagonist and a thiazide diuretic, hypertension (inability to achieve target values <140/90 mmHg). Recent reports demonstrate the effectiveness of adding spironolactone to triple therapy, reducing blood pressure by an average of 22/9.5 mmHg. Thus, spironolactone can be recommended as a component of antihypertensive therapy in patients with resistant hypertension. Adverse events. There is evidence that the severity of edema associated with the use of dihydropyridine OCs may be reduced by the addition of RAAS blockers, which may also reduce the incidence of hypokalemia caused by TDs. On the other hand, the use of β-blockers is associated with an increase in the incidence of diabetes mellitus (DM), and when using a combination of TD with β-blockers, a more significant increase in the incidence of newly diagnosed DM is likely, but paradoxically this does not increase the incidence of diabetes-related heart disease. –vascular endpoints, as shown in the ALLHAT study. The NICE recommendations provide data from a meta-analysis that revealed an increase in the incidence of newly diagnosed diabetes with the use of β-blockers and TDs in comparison with newer drugs [11]. The findings are based on the assumption that there are no differences in long-term morbidity and mortality between drugs within the same class. Among AKs, amlodipine has the largest evidence base. In studies examining ACEIs and ARBs as part of combination therapy in patients with hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases, various representatives of these classes were studied, and no differences were found between them. It is believed that among thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics, chlorthalidone in moderate doses has the greatest evidence base for long-term benefits (compared to other TDs in lower doses). Unfortunately, further studies comparing drugs in this class seem unlikely. The most frequently used β-blocker drug in trials was atenolol, and it was repeatedly stated that if other members of this class had been used in trials, the results would have been different. This seems unlikely, because The adverse events identified in the ASCOT study, which included an effect on blood pressure variability and an increase in central intra-aortic pressure compared with amlodipine (both associated with increased cardiovascular risk), most likely occur with the use of most beta-blockers [14]. . There have been no studies examining the effects of β-blocker therapy with additional pharmacological properties (eg, β-1, β-2 and α-blocker carvedilol) on long-term outcomes in patients with hypertension. Fixed-dose combinations and their benefits on prognosis A recent review of the potential benefits of fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) over corresponding drugs taken alone found that FDCs are associated with significant improvements in adherence and a small increase in duration of dosing. The degree of adherence to treatment using FDCs, according to a meta-analysis of 9 studies, is 26% higher compared to taking the same medications separately [23]. According to studies containing information on blood pressure values, the use of FDC is associated with a slight additional decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (4.1 and 3.1 mm Hg, respectively) [22]. If maintained over the long term, such differences in blood pressure may translate into real benefits in cardiovascular outcomes. Conclusion The majority of patients with hypertension require treatment with two or more drugs from different classes of antihypertensive drugs to achieve target blood pressure values. Combination antihypertensive therapy should be prescribed to patients with blood pressure above target values by more than 20/10 mmHg. Rational (preferred) and possible (acceptable) combinations of drugs should be used. Fixed combinations increase adherence to therapy, which increases the frequency of achieving target blood pressure values.

References 1. Page IH The MOSAIC theory // Hypertension Mechanisms. – New York: Grune and Stratton, 1987. P. 910–923. 2. Mimran A., Ribstein J., Du Cailar G. Converting enzyme inhibitors and renal function in essential and renovascular hypertension // Am. J. Hypertens. 1991. Vol. 4 (Suppl. 1). 7S–14S. 3. Dickerson JE, Hingorani AD, Ashby MJ et al. Optimization of antihypertensive treatment by cross–over rotation of four major classes // Lancet. 1999. Vol. 353. P. 2008–2013. 4. Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, Jordan RE Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomized trials // BMJ. 2003. Vol. 326. P. 1427–1435. 5. Attwood S., Bird R., Burch K. et al. Within–patient correlation between the antihypertensive effects of atenolol, lisinoprill and nifedepin // Hypertens. 1994. Vol. 12. P. 1053–1060. 6. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR et al. Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh Report of the joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure // Hypertens. 2003. Vol. 42. P. 1206–1252. 7. Russian Medical Society for Arterial Hypertension (RMAS), All-Russian Scientific Society of Cardiologists (VNOK). Diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension. Russian recommendations (fourth revision) // Systemic hypertension. – 2010. – No. 3. – P. 5–26. 8. Messerli FH, Mancia G, Conti CR et al. Dogma disputed: can aggressively lower blood pressure in hypertensive patients with artery disease be dangerous? //Ann. Intern. Med. 2006. Vol. 144. P. 884–894. 9. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) // JAMA. 1991. Vol. 265. P. 3255–3264. 10. Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E. et al. Prognostic significance of visit–to–visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension // Lancet. 2010. Vol. 375. P. 895–905. 11. Nice guidelines. Management of hypertension in adults in primary care. 2007. www.nice.org.uk. 12. Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL et al. ACCOMPLISH Trial Investigators. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients /// NEJM. 2008.Vol. 359. P. 2417–2428. 13. Julius S., Kjeldsen SE, Brunner H. et al. VALUE Trial. VALUE trial: Long–term blood pressure trends in 13,449 patients with hypertension and high cardiovascular risk // Am. J. Hypertens. 2003. Vol. 7. P. 544–548. 14. Williams B, Lacy PS, Thom SM et al. CAFE Investigators; Anglo–Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial Investigators; CAFE Steering Committee and Writing Committee. Differential impact of blood pressure–lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes: principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFE) study // Circulation. 2006. Vol. 113. P. 1213–1225. 15. Makani H., Bangalore S., Romero J. et al. Effect of rennin–angiotensin–system blockade on calcium channel blockers associated peripheral edema // Am. J. Med. 2011. Vol. 124. P. 128–135. 16. Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Cooper–DeHoff RM et al. INVEST Investigators. A calcium antagonist vs. a non-calcium antagonist hypertension treatment strategy for patients with coronary artery disease. The International Verapamil–Trandolapril Study (INVEST): a randomized controlled trial // JAMA. 2003. Vol. 290. P. 2805–2819. 17. Alviar CL, Devarapally S, Romero J. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dual Calcium Channel Blocker Therapy for the Treatment of Hypertension: A Meta-analysis // ASH. 2010. 18. Alvares–Alvares B. Management of resistant arterial hypertension: role of spironolactone versus double blockade of the rennin–angiotensin–aldosterone system // J. Hypertens. 2010. Jul 21. . 19. Bailey RR, Neale TJ Rapid clonidine withdrawal with blood pressure overshoot exaggerated by beta-blockade // BMJ. 1976. Vol. 6015. P. 942–943. 20. Chapman N., Chang CL, Dahlof B. et al. For the ASCOT Investigators. Effect of doxazosin gastrointestinal therapeutic system as third–line antihypertensive therapy on blood pressure and lipids in the Anglo–Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial // Circulation. 2008. Vol. 118. P. 42–48. 21. Chapman N., Dobson J., Wilson S. et al. On behalf of the ASCOT Trial Investigators. Effect of spironolactone on blood pressure in subjects with resistant hypertension // Hypertens. 2007. Vol. 49. P. 839–845. 22. Gupta AK, Arshad S., Poulter NR Compliance, safety and effectiveness of fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive agents: a meta-analysis // Hypertens. 2010. Vol. 55. P. 399–407. 23. Bangalore S., Kamalakkannan G., Parkar S., Messerli FH Fixed-dose combinations improve medication compliance: a meta-analysis // Am. J. Med. 2007. Vol. 120. P. 713–719.